When I first shared news of my current project on social media, it attracted a couple of comments describing it as pointless, borderline-idolatrous, irrelevant to the gospel, and a waste of money. Mostly, this sort of thing just makes me smile and suggests to me that I’m probably doing good work—talking about the Bible (Paul’s letters no less) and masculinity is unlikely to be everyone’s cup of tea. But on this occasion it also prompted me to want to articulate why I think this work matters.

My doctoral research looked at different ways that Paul describes himself in his letters through the lens of masculinity studies. There has been a trend over the past fifteen years or so in research on biblical masculinities to measure certain biblical characters up to Graeco-Roman ideals of masculinity. Essentially, I argue that when it comes to Paul: it’s complicated (when is that ever not the case with Paul?). For example, when he applies various maternal imagery to himself—birthing the Galatians, and nursing the Corinthians and the Thessalonians—is he subverting ideas about what it is to be a man? And if so, is that good news for thinking about Paul’s stance towards women, or is he simply appropriating female imagery without much regard for the lives of real women? Does he model a distinctive form of masculinity by describing himself this way? Or is this actually a familiar rhetorical pattern among Graeco-Roman writers because women’s bodies are good to ‘think with’ (to quote Peter Brown)? Masculinity is complicated (you can read more on how I navigate Paul’s maternal masculinity in this article).

And yet how often do we behave as if masculinity were simple, a known entity so obvious that it doesn’t require acknowledging most of the time. The ‘we’ here could either be ‘we’ as in the academy or ‘we’ as in the Church. Paying attention to gender in biblical texts has for a long time often meant (and is often assumed to mean) paying attention to the women in biblical texts. So as far as Paul is concerned, what does he have to say about women and what they are or aren’t allowed to do? Women are marked as being gendered; men are not. Men are simply men, the default human being (this assumption extends far beyond the Church and biblical studies, of course—see Caroline Criado Perez’s somewhat devastating look at the way men as the default human being is woven throughout all different parts of society). Masculinity studies makes masculinity an object of study; men are no longer the default to which women are ‘other’. Adopting this perspective allows men to be recognised as gendered subjects too, making it possible to analyse masculinity not as something static, but constantly in the process of being remade.

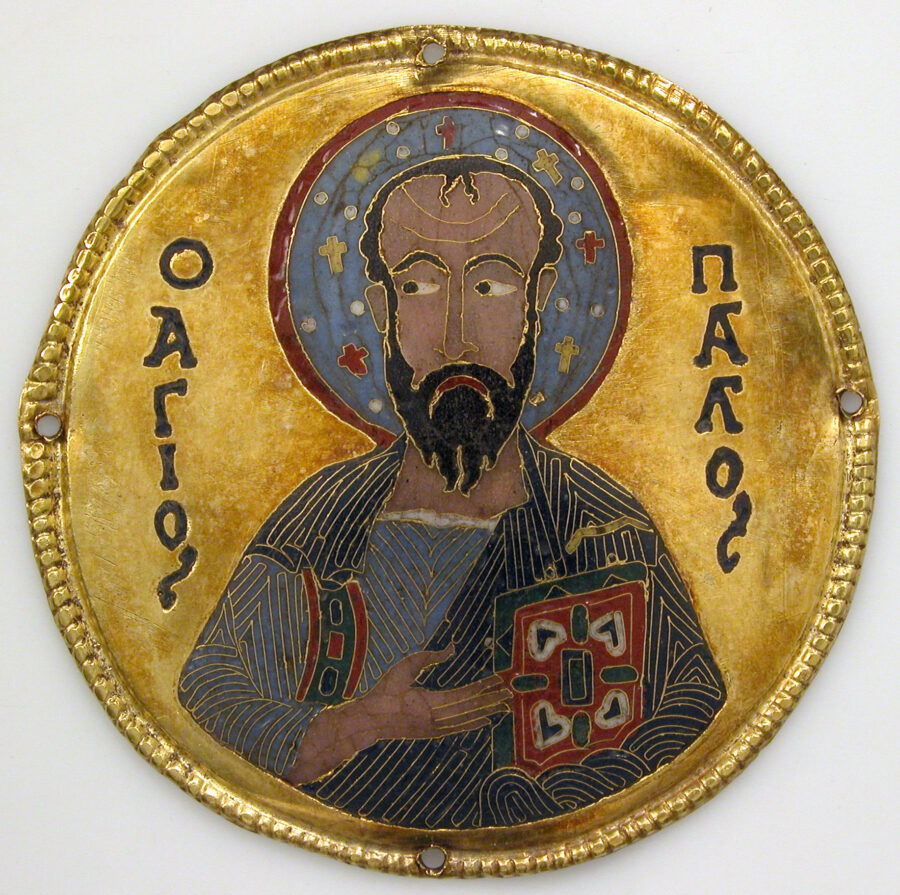

Paul’s letters have been hugely significant to debates about the role of women throughout the Church’s history. My academic research, in conjunction with the research of others, has sought to redress the invisibility of Paul’s own gendered status in these conversations—as well as the gendered status of his interpreters and the impact that might have on reading the apostle’s letters (some initial research I’ve started on that latter aspect here). My current project is about visualising this conversation and bringing it into a more public domain. To return to the example I gave earlier; what would it look like to visualise Paul not on the road to Damascus, or preaching, or writing letters as we often see him in artistic reception, but as part of a ‘milky trinity’ nursing the Thessalonians with Timothy and Silvanus? Or enslaved to other believers? Or with a body marked by persecution? And so on. It is up to us how we remember Paul, and despite the breadth of material he gives us in his letters we rarely contemplate the variety of apostolic portraits offered.

My hope is that by visualising Paul in unfamiliar ways we will be able to broaden the conversations we have about the apostle and gender. This serves the Church by challenging the idea of a monothetic ‘biblical masculinity’ where that notion resides, inviting us to interpret Paul in multiple ways. But this work also serves the academy by ‘reversing the hermeneutical flow’, to borrow from Larry Kreitzer’s work on fiction, film, and biblical texts. The reception of biblical texts allows us to revisit passages familiar to us with a different perspective, often drawing out elements of the text that we hadn’t noticed previously.

Beyond the academic outputs that are possible in association with this project, it also has the potential to be life-giving and liberating for those for whom Paul’s letters are scripture. That’s not to say that this project will position Paul as a proto-feminist model of masculinity (as I said earlier, masculinity is complicated). But simply acknowledging this complexity may well, I suspect, have rich theological value for many. That seems a worthwhile use of time and money to me.

So, I’m currently looking for an artist (of any medium) to collaborate with me to bring this vision to life: if that’s you, or someone you know, do take a look at the full details here and consider submitting a proposal (budget is £10k, you don’t need to be resident in the UK to apply, and the deadline is 11th March).

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.