The Bible bursts the bonds of our hermeneutical strategies. The Scriptures as the medium of divine communication are what Karl Barth called a “free Bible”. This is good news: the canon imposes itself upon us readers, transgressing the procrustean bed we inevitably bring to the table as interpreters. For Barth this fact necessitates the development of a “free exegesis”, which means that “Bible exegesis should be left open on all sides” and that “self-defence against possible violence to the text must be left here as everywhere to the text itself” (CD I/1, p. 119). This is a very important word for us to hear; it reminds us of the power of the Word–what we really need to happen in the reading, interpretation, and proclamation of the Bible is something that no method can produce. But does this conception of the canon invalidate reflection on the hermeneutical process? Does it mean that we cannot learn how to be better interpreters of the Bible? No. Rather, such a conception of holy writ demands only that we not set a norm over the biblical canon, that we attempt, carefully and prayerfully, to read the Bible in a position of submission to it, allowing it to impose itself upon us as a Word from God.

The Bible bursts the bonds of our hermeneutical strategies. The Scriptures as the medium of divine communication are what Karl Barth called a “free Bible”. This is good news: the canon imposes itself upon us readers, transgressing the procrustean bed we inevitably bring to the table as interpreters. For Barth this fact necessitates the development of a “free exegesis”, which means that “Bible exegesis should be left open on all sides” and that “self-defence against possible violence to the text must be left here as everywhere to the text itself” (CD I/1, p. 119). This is a very important word for us to hear; it reminds us of the power of the Word–what we really need to happen in the reading, interpretation, and proclamation of the Bible is something that no method can produce. But does this conception of the canon invalidate reflection on the hermeneutical process? Does it mean that we cannot learn how to be better interpreters of the Bible? No. Rather, such a conception of holy writ demands only that we not set a norm over the biblical canon, that we attempt, carefully and prayerfully, to read the Bible in a position of submission to it, allowing it to impose itself upon us as a Word from God.

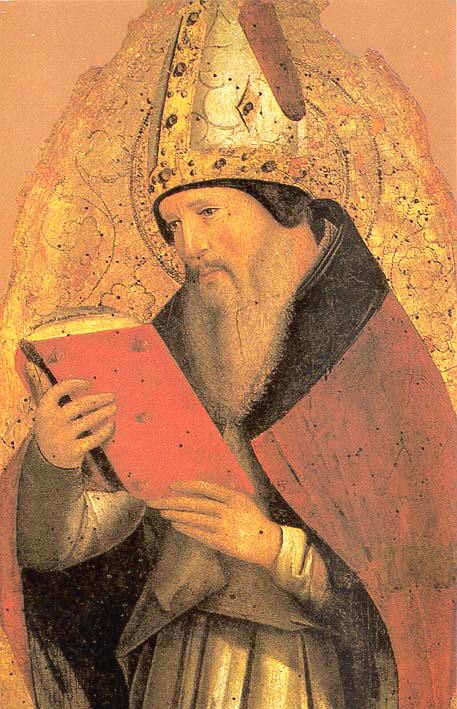

I am sure that one could learn a hermeneutical strategy from Karl Barth. However, over the next few weeks I would like to dig a bit deeper in the theological tradition, enrolling in St. Augustine‘s Institute for Biblical Hermeneutics. The course is free, and there is only one text to buy–the instructor’s own de doctrina christiana (variously translated as “On Christian Doctrine”, “On Christian Teaching”, or “Teaching Christianity”). Started in 396 but not completed until 427, this work is Augustine’s attempt to teach the clergy and devout lay people of Africa how they, as believing Christians, should read the Bible for the profit of themselves and others, and to the glory of God. We have here a master-teacher (Augustine was a true man of learning) aiming to make us competent interpreters and teachers of the Bible. Augustine thus locates the study of the Bible squarely in the context of discipleship. In this sphere there is no learning that does not involve teaching.

So in this and my next three posts, I would like to look at each of the four books of this classic text, providing lucid summaries and drawing out the key principles so that we can evaluate them and, perhaps, employ them in our own lives as disciples. My experience in pastoral ministry and my education in biblical and theological studies have made me painfully aware that, for all the access we have to biblical data and research tools, we are not necessarily better readers of the Bible. This also (especially?) applies to those like myself who have a decent education in reading and interpreting the text. So perhaps someone old and strange like Augustine can provide us with some much-needed wisdom as to the exegetical task.

As a preliminary, Augustine clarifies the nature of biblical study. As I mentioned already, he establishes from the outset that this endeavor is not to be undertaken outside of the context of a passing-on of knowledge. In fact, for Augustine, genuine learning cannot take place outside the context of service toward others. “Every kind of thing, you see, which does not decrease when it is given away, is not yet possessed as it ought to be, while it is held onto without also being given out to others” (1.1). As a second important point: Augustine adopts some terminology about means and ends, the two basic ways we comport ourselves toward objects in the world. There are things which are to be used (means) and things to be enjoyed (ends), and still some things which are both used and enjoyed. With these two preliminaries out of the way, the vast bulk of book 1 is dedicated to providing the guiding hermeneutical principles.These principles do not take the form of a general theory of reading and interpretation. Instead, Augustine starts by extrapolating an ontology from the central reality of the Christian faith–the Triune God’s rescue of fallen sinners through the incarnation of the Son. This ontology does two things. (1) It provides a meta-narrative within which we will interpret the narratives of scripture. (2) It points out the spiritual life that scripture draws us into, and the spiritual life which is itself necessary for scriptural interpretation.

What is the chief end of man? That is to say, what is that which we may properly “enjoy”? It is the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This God is not any old thing, but the cause of all things. Our effort to define God’s being in ontological terms is somewhat futile. To the biblical definition of God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, we may only add that God is the thing “than which nothing is better or more sublime” (1.7). This highest being is by definition immutable. This is so for the stated reason that the truth by which we make an evaluation is itself timeless and unchanging. (There are probably other arguments for divine immutability that are assumed by Augustine. For an analytic treatment of immutability, timelessness, and degrees of reality in Augustine’s thought more broadly, see Leftow, Time and Eternity, pp. 73-111). The basic takeaway from this is that human creatures are such that they long (whether they know it or not) for an object of desire that satisfies, an object of desire that lasts and provides a solidity of being, something that does not fade or die, something “unchangeably alive” (1.10). In order to know and commune with the immutable God, our minds have to be purified, perceive the light, and cling to it. But Augustine thinks we are incapable of this. Rather, we are only made capable of this through the incarnation of God’s immutable wisdom in a human mode. God fits like to like, and matches the pride of our fall with the humility of Jesus Christ. Beyond just dying and rising on our behalf in a juristic sense, Christ’s death and resurrection become models for our lives. The death we die is to the habits we inherit by virtue of the sin of Adam, and the resurrection is the start of the the new life that will occur finally in the eschaton.

So we can only truly “enjoy” the triune God, whom we may only know through the incarnate Word Jesus Christ. All other things, Augustine tells us are to be “used” for this end. This includes ourselves and our neighbors. If we turn towards ourselves or our neighbors as ends, we inevitably wreck ourselves as we are detached from the only stable reality which grounds our existence–the immutable love of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It is not that we do not “love” other things (like ourselves or our neighbors), but rather that love is a comportment toward things in light of their chief end. I love myself truly when my body and its desires are subject to my soul, which is seeking God above all. I love my neighbor when I treat my neighbor as a fellow, called to delight in God above all. This grounds an ethics that is neither libertarian nor ascetic with respect to the body, and which regards all people in their highest calling, regardless of how they are actually living. In other words, we should read the world “use” in some sort of crude, instrumental sense. Both using and enjoying are to be done in love.

In simple terms, what Augustine has done is expound Jesus’ own hermeneutical “rule of faith” (Luke 10:27: “‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’; and ‘you shall love your neighbor as yourself'”), allowing the content of the first command to inform the interpretation of the second. This rule of faith is not all there is to be said about scriptural interpretation, but it does a couple of important things. In the first place, it provides us with a teleology for biblical interpretation, a sine qua non of understanding: “if it seems to you that you have understood the divine scriptures, or any part of them, in such a way that by this understanding you do not build up this twin love of God and neighbor, then you have not yet understood them” (1.36). Second, this rule of faith provides us with a hermeneutical safeguard such that even if we misunderstand the biblical author’s intention (which is very important for Augustine!), if we misinterpret in a way that aims to build up this “twin love” then our error is only of the benign sort and not pernicious.

The overall point of the first book is to put hermeneutics in a spiritual setting. The prerequisite for biblical hermeneutics is a life of active faith. The key to interpreting individual passages, as we will see, is to keep always before us this centre of the Bible, and to live in it from the heart. Interestingly, this is also the end of biblical hermeneutics. We inhabit this hermeneutical spiral partly because for both us and our neighbor, faith has not yet become as sight. Another reason is because we ourselves have to go from faith to faith, ever deepening our love and understanding of the infinite God.

4 Comments

Leave your reply.