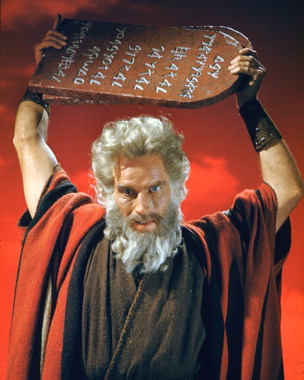

The early Church father Tertullian once asked a similar question to explore the connections between Christianity and Greek thought. This question is designed to explore a literary connection between how we watch movies and how we read the Bible. The issue here is how are we to interpret the Old Testament narratives? Are they history or a story? How we understand the genre of the historical books in the OT will determine how we read, interpret, and apply them.

Often the Bible is misconstrued by both the Academy and the Church in the domain of history. The Academy with its higher criticism of German descent and modernistic approaches to interpretation have mistaken Scripture, especially the Old Testament narratives, as history which is severely flawed. To the Academy, the introduction of the divine into the course of human history only magnificently displays the lack of “real” history. The Bible more accurately belongs to the domain of fictitious accounts of a small people group attempting to solidify themselves as a nation with a coherent history.

On the other side of the chasm, the Church has mistaken Scripture in just the same way, although they have reached a different conclusion. To the Church and its many devotional readers, the OT narratives are certainly historical. Yet, the Church has seen them in a more apologetic fashion (perhaps as a result of the academy), and have spent much of their time assessing the inerrancy of the texts. To them, the Bible is purely history, inerrantly recording what has “really happened”. Scripture has functioned as a window into the ancient world in a time where God was visibly working, yet this window is kept pristinely clean from the actual dust, sweat, and blood of the ancient world.

Both of these institutions embark on similar enterprises-to encounter the text-but arrive at opposite ends of the spectrum. What is common is that both affirm that Scripture is attempting to record events as they happened, or in other words, Scripture is just like any other modern history textbook. But is this presupposition correct? Both of the conclusions- the Bible is flawed history and the Bible is flawless history-fail to engage the text faithfully and fail to place the Bible into its ancient Near Eastern historical context.

Historiography in the Ancient Near East

History writing in the modern sense, i.e. to unbiasedly record events “as they happened” did not exist in the ancient Near East. There were no investigative journalists back in the day. History in ancient terms could be better called “historiography.” K. Lawson Younger explains that, “The historical work is always the historian’s interpretation of the events, being filtered through vested interest, never in disinterested purity.” This literary enterprise of the ancient Near East can be characterized as creatively arranging historical events and persons to tell a story designed to instruct a particular audience. Thus, these histories should be better thought of as stories that tell of historical events. The author is creatively arranging and explaining historical events, not as they happened per se, but as they serve the didactic purpose and polemical interests of their authors, yet this purpose is never to just simply state facts as they happened. Rather, in an optimistic view of these narratives, these authors seek to instruct their readers about how the world is and why it is this way. In a more negative view of these narratives, these authors simply seek to propagate and legitimize their king and deity. However, this doesn’t make the texts any less “historical,” for the writers were never intending to write history as we know it today. When it comes to scripture, the reader must take the text on its own terms; historicity is then dictated by the text. V. Philips Long writes, “In other words, only where a text’s truth claims involve historicity does a denial of historicity become a denial of the truth value of the biblical text, and thus become a problem for those holding a high view of Scripture.” Thus, a text’s historical value is to be disregarded only when it claims to be accurate history and is proven false by verifiable means.

For you to get a better picture of this, let me provide an example from the ancient world. The Armant stela of Thutmose III is a monumental inscription found in the temple of Montu in Armant, which is near modern day Thebes. The text details the Pharaoh’s athletic prowess, his sporting skill, and briefly mentions his conquests in his first campaign. After a rather lofty introduction, the author makes this claim that may give some hope to those that are skeptical of historiography: “It is without deception and fabrication, and without exaggerated claims that I state the truth regarding that which he performs among and in front of his whole army.” Yet, the inscription then follows with just a few of Thutmose III humble accomplishments, “He slew seven lions by shooting arrows in an instant and carried off a herd of twelve wild bulls in one hour after breakfast time occurred . . . As he was returning from Naharin, he finished off 120 elephants in the highlands of Ny. He ferried across the Euphrates River and trampled the cities on both sides, they being destroyed forever with fire.” Behold, historiography in the ancient Near East! When read in a modernistic context, this seems absolutely absurd, but in its historical context, this is normative. The author, is seeking to immortalize Thutmose III and to legitimate his rule. This is clearly hyperbole, as it would be rather difficult to slay seven lions in an instant or take down a herd of wild bulls before lunch in bronze age Mesopotamia. Furthermore, this inscription describes in brief detail Thutmose III’s campaign in Mesopotamia. However, this account is again hyperbolic. Even though his campaign did result in the conquering of Canaan and parts of upper Mesopotamia, the text depicts the campaign in a different light. It says that Thutmose III destroyed the cities on both sides of the Euphrates The hyperbolic boasting culminates in a double edged propaganda, “His majesty returns each occasion, his attack happens in bravery and victory, he causing that Egypt be in its (original) state, just as it was when Re was in it as king.” The author casts the Pharaoh in the reflective shadow of Re, the sun god. The author legitimizes the king by describing him as having returned Egypt to a golden age.

Historiography in the Ancient Israel

This is just one of many examples of how history is recorded in the ancient Near East. Historiography is ancient Israel was virtually the same as in the rest of the ancient Near East. Israelite historiography shapes historical events for a didactic purpose, just like the writers of the mentioned texts did. However, there is one primary difference between Israelite historiography and the ancient Near East. While ancient Near Eastern texts usually seek to legitimate the king and the deity, Israelite historiography usually focuses on Yahweh at the expense of the people and their king. An obvious example of this is found in the book of Judges. Every leader is a flawed leader, and the people continually fall into idolatry and eventual oppression and enslavement. There is no legitimization in this book except that of the gracious Yahweh. Another example is the difference between Samuel-Kings and Chronicles. The former focuses on the sin of Israel to explain Yahweh’s reasoning for the exile. The latter is much more hopeful as the post-exilic author is remembering Yahweh’s grace in the pre-exilic history. The focus is rarely on the people, and if it is, the narrative usually de-legitimizes them.

Scripture as story

So back to our original question, What has Hollywood to do with Jerusalem? How should the Church and the Academy read these OT narratives? I would argue that we should view them as a true story based upon historical events that seeks to tell us about God’s acting in our world. In short, the Bible has more in common with “Band of Brothers” than it does with a WWII history textbook. Therefore, we should read these stories like we watch good movies. We must pay attention to the characterization in the text, the way the scenes change and jump back and forth. The way the OT narrative zooms in on a “certain man” is the same way the camera zooms in on the actions of one man in the midst of the world. The same way that we feel and experience films is exactly how we should feel and experience Scripture. The OT narratives tell tragic stories of death and pain and also of triumphant victories over the evil enemies. Instead of looking behind the text to determine their “historicity,” informed readers should simply take the text on its own terms to discover its didactic purpose. When we seek to find the author’s communicative intention, questions regarding historicity step aside to let the text speak and teach for itself. “Did this really happen?” is replaced by, “What is author trying to communicate by describing this scene and event in this way?” When you come to the text to listen to what it has to say, you have a better chance of actually hearing and learning from it. In doing so, Scripture as God’s revelation is able to speak to you and transform you.

Works Cited

Hoffmeier, James. “The Armant Stela of Thutmose III.” In The Context of Scripture, edited by William W. Hallo. Vol. 2, 18-19. Leiden: Brill, 1997.

Long, V Philips. Foundations of Contemporary Interpretation. Vol. 5, The Art of Biblical History. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1994.

Younger, K Lawson. Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing. New York: T & T Clark, [2009].

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.