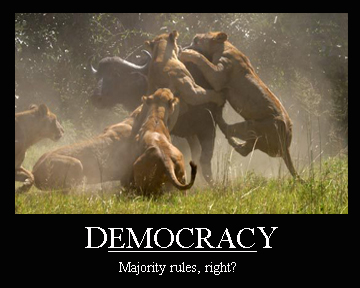

In a democratic society there is no greater or more powerful argument for a position than that it is the majority view. Majority positions are not just descriptive of a particular group, but go even further by implementing that position in a concrete way. In this way, we might say that the majority has the ability to make something true. If the majority decides that X ought to be the case then, on the level of that society’s accepted norms, it becomes the case. This has frightening as well as beneficial consequences, and it is at the heart of not only the western political process but also the western worldview. Consensus is King.

However:

As just about anyone who has taken an introductory course on logic knows (or ought to know) this type of reasoning completely invalidates the argument into which it is injected. It is broadly known as the “Bandwagon Fallacy.” It is a fallacy for obvious reasons. It is obviously the case that reality cannot be determined simply on the basis of a popular vote. History is filled with examples.

Nevertheless:

I find that this democratic way of thinking is pervasive in many areas of our western world. In the past I have written about the false notion of “progress” or “the wrong side of history” that I think is, in large part, driven by this sort of thinking. Contemporary debates furnish plenty of examples. But it is also present at the level of so-called impartial science. “New Atheism”‘s attack on religion falls very heavily into this category. Another area I constantly encounter this is in my own field of biblical studies. I will give one extended example.

I have recently been reading John J. Collins’ Beyond the Qumran Community, a book discussing the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS). This book was recently recommended at a meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature, arguably the most prestigious society for biblical studies, as the new standard work on the background of the DSS. This is not a popular level study, and Collins is a world-renowned scholar with hundreds of published works.

Here is my example: When it comes to dating the ministry of the “Teacher of Righteousness” clues have been sought from a passage is the Damascus Document (CD) in which this movement is said to have arisen 390 years after the destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar. Collins’ response to this methodology is that this passage cannot be used this way because “all scholars acknowledge the number is symbolic, derived from Ezekiel 4.5.” (pg. 92). This is a remarkable claim! It is interesting to find it in a work of this prestige for several reasons:

First, Collins gives no substantiation for this claim. There is no footnote following the quoted sentence giving us bibliographic data confirming that his “all” is truly all. If it is meant to be merely descriptive of an actual survey of scholarship then it would have some value, but it isn’t and so it doesn’t.

Second, because it is not descriptive, and for other contextual reasons, it is clear that Collins intends this sweeping statement to be taken as a foundational piece of evidence. This is highly problematic because it not only invalidates his argument, but also because it could very easily be found to be false. All a critic has to do is find one, single scholar who does not think that 390 years in CD or Ezekiel is symbolic. (Collins own footnotes betray him when he cites works disputing his very claim. Are they scholars or not, based on his initial statement?)

Third, as Collins’ continues it is clear that he has no other evidence to offer. He even admits “we do not know how the author understood the chronology of the Second Temple period.” But if this is so then how do we know that it is meant to be symbolic?! The answer is simple: all scholars tell us that this is so.

This kind of statement is a major problem, not only in Collins’ work, but in “scholarship” as a whole. (Bear in mind, the problem here is not Collin’s claim (390 is symbolic) but the method by which he argues for that conclusion (390 is symbolic because all agree that it is so)) The consensus is put to work in a very problematic way. If these statements were meant to be taken as purely and merely descriptive statements of fact then we might have something to learn. It might be useful to know that a certain position is widely or universally held by qualified individuals. But that has nothing to do with whether or not such a position is actually true. The two uses should never be confused, but they almost always are. It seems that more often than not these statements function basically as intellectual bullies. What is implicit in statements like this is: If all scholars say X, and you say something else, then that just proves that you aren’t a scholar. I experienced exactly this type of reasoning, and in quite explicit terms, at a serious academic conference I recently attended. In multiple conversations and presentations it was made quite clear that dissent from the majority didn’t just put you in a minority position, but led to expulsion from “the guild”.

It seems to me that statements like these are really just giving us information about what the author thinks a scholar is, not what is actually the case in existing literature or the text under discussion. The bully is meant to show opponents to the door.

Consensus might be King in the political system many of us find ourselves within, but kings can’t dictate truth. Majority opinion cannot be cited as evidence, and it doesn’t have any bearing on whether or not an argument is true. My perhaps tedious example will probably be interesting only to academics working in biblical studies, but if I can convince even one of you to stop trying to play the bully then I am content. Whatever merits the democratic system has as a political method of ordering society, it cannot be and should never become our method of determining truth.

1 Comment

Leave your reply.