Many of us know Job 19 because, if we know anything of the actual Joban dialogue, we know Job 19:23-27. It is the most famous passage from the book. In the text Job states his belief that a day will come when he will physically see God after his death. Over the past couple of weeks, I have looked at Job and how he points to the true man of sorrows, Jesus Christ. I plan to do that here as well but I also want to explore Job’s theological development up to this point in addition to supplying some pastoral thoughts on the passage.

Oh that my words were written! Oh that they were inscribed in a book! Oh that with an iron pen and lead they were engraved in the rock forever! For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold, and not another. My heart faints within me!

While this verse is both known and quoted by many, it is infrequently realized that this is a crucial turning point in the actual narrative. Up to this point, Job has been content to plead with his friends for compassion and mercy. Even at the beginning of chapter 19 we see Job asking his friends, “How long will you torment me and break me in pieces with words? These ten times you have cast reproach upon me; are you not ashamed to wrong me” (Job 19:1-2)? This banter has been going on for some time but it all comes to a sudden head at the end of chapter 19. Before Job makes his shocking statement he says to his friends one last time, “Have mercy on me, have mercy on me, O you my friends, for the hand of God has touched me! Why do you, like God, pursue me? Why are you not satisfied with my flesh” (Job 19:21-22)? The narrative has been set up, to this point, in such a way that we would expect a friend to step in here and provide an answer. But Job never lets it go that far. He has given up on them. And thus he turns to the only one who can help, God himself (Job 19:23-27). From this point onward, Job has no interest in pleading with the friends. He will debate their theology, he will defend himself but he will not plead for their aid any longer.

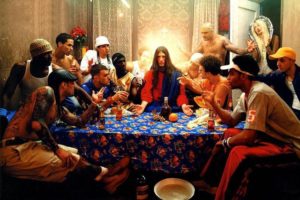

The friend’s betrayal is now total. In many ways, the friend’s actions foreshadow an even more heinous act of betrayal. As we read Job, we can’t but help of think of Jesus Christ. Job tells us, “All my intimate friends abhor me, and those I loved have turned against me” (Job 19:19). The echo of Job’s words are heard in Psalm 41:9, “Even my close friend in whom I trusted, who ate my bread, has lifted his heel against me.” The fulfillment of this prophecy in Judas’ betrayal of Jesus (John 13:26-27) is the height of treachery in all of human history. So Jesus Christ stands with Job and all those who have experienced this type of duplicity.

The Christian life is often a lonesome one. And I am not talking about the type of banal loneliness that is so often whined about in western society. To be fair, there is undoubtedly a loneliness that is created by ever invading technology and the industrialized west. But this is not the loneliness that Job or Jesus experienced. We are talking about a loneliness that stems from a relentless commitment to God’s ways and his character. Such persons are dedicated to God in such a way, so in tune with the heart of God, that their suggestions seem out of place to the bulk of the religious world. So out of place that the religious world turns their vitriol against such people. And what makes it even worse is that the stringing criticism is cloaked in the language of religious zeal. This is what Job experienced with his friends and it is what Jesus experienced with the Pharisees.

And yet in this hour of loneliness, hope can be found. Very few can say that they pursued God in such a way that they experienced a horrific betrayal by those who loved them most (at least in the west). Yet for those waiting for dawn to break, we have the cries of Job in chapter 19:23-27 to point us to the foundation of joy. In this passage, we find Job’s ultimate creed. I say this because Job is not venturing into theological pontification. Rather his statement is deeply doxological. It is the truest creed of all because it is real. It is lived. Job could have written voluminously on a vast array of theological topics but at this point such writing would matter little. What matters now is finding a rock to cling to in the midst of a horrific situation. Job knows that this rock is God himself. Thus Job shows himself to be more than an idle theological babbler. For Job, their is a vital integration of theology and faith that helps provide support to his ultimate creed.

As I have stated in past blogs, the trajectory of Job’s theology throughout the course of the narrative is simply remarkable. Job has gone from hoping that someone can mediate for him (Job 9:32-35) to being sure that someone in heaven was witnessing on his behalf (Job 16:19) to now, being certain that he will one day see God in some sort of resurrected body (19:23-27) in order to receive his final vindication.

What Job is actually describing in the text at hand is a matter for serious debate among many commentators. Does Job believe in bodily resurrection? Or does he still expect vindication in this lifetime? Some would suggest that Job still expects vindication in the here and now. After all the narrative does close with Job stating that his eye has seen God (Job 42:5). These same people would also suggest that a belief in resurrection was non-existent in Jewish theology during Job’s time. While I am sympathetic to some of this reasoning, I believe it falls short upon further textual examination. Ultimately I want to offer a few reasons as to why I think Job does believe in some sort of resurrected existence. His theology is no developed New Testament understanding of resurrection and glorification but the general theme of resurrection is nonetheless present. First, it hardly makes sense for Job to wish his words be engraved in a monument if he expects to find vindication in this lifetime. Second, the passage hints at certain eschatological elements. The use of “at last” (v. 25) and “after” (v. 26) seem to suggest some sort of “afterward.” After something has been completed, Job expects to see God. Given that Job’s speech is ripe with expectation of death (Job 17:1), it seems plausible that the event, which he is referring to, is his own death. Third, the resurrection motif is strong in other parts of the book. Its presence in chapter 14 is undeniable (Job 14:7-14). All of this leads me to conclude that Job does in fact believe that he will one day see God in some sort of post mortem existence.

It is this belief, that he will find final vindication in the after life, which Job clings to. In Job’s cries we are able to see that when all others have failed, there is one who will deliver. Even if that vindication is not experienced in this lifetime, God will correct all things that are remiss. This is Job’s hope. And it is ours as well.

For this light momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison… 2 Corinthians 4:17

1 Comment

Leave your reply.