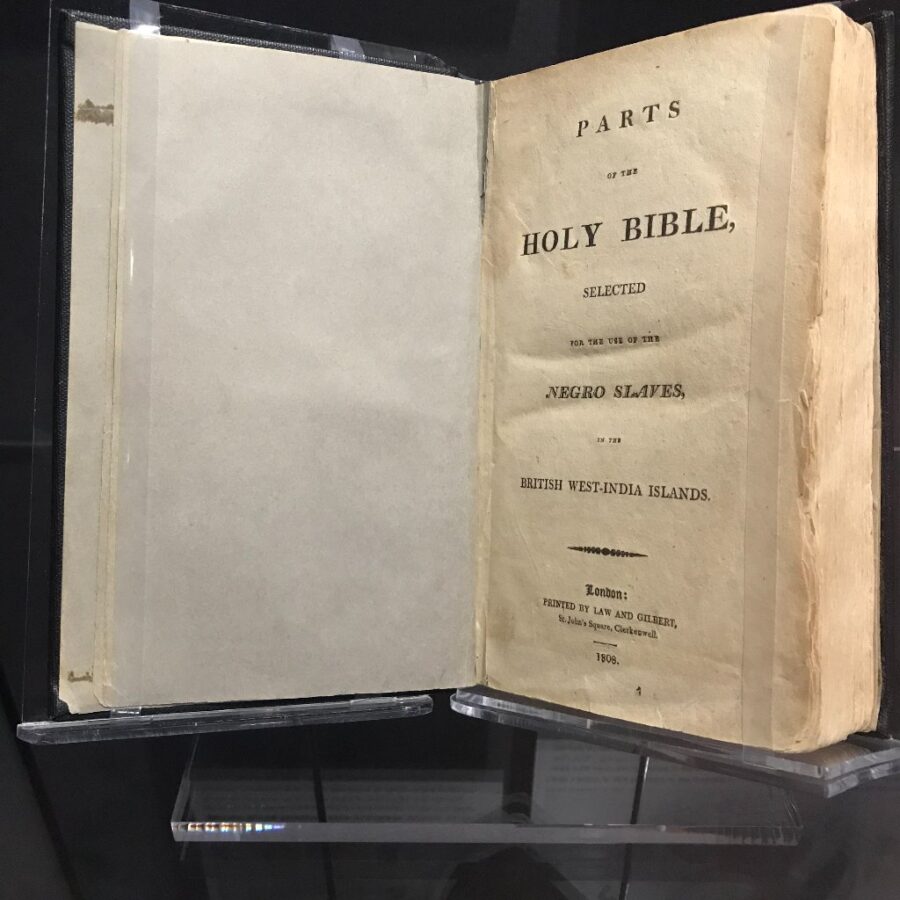

The Museum of the Bible recently opened an exhibit entitled, “The Slave Bible: Let the Story be Told.” The centerpiece is a book called, “Parts of the Holy Bible, selected for the use of the Negro Slaves, in the British West-India Islands” published in 1808. Originally published in London in 1807, this book was apparently used to educate British-owned slaves in both reading and religion. The interesting thing about the work is that it features only a selection of the biblical text. The Museum of the Bible explains:

“Unlike other missionary Bibles, however, the Slave Bible contained only “select parts” of the biblical text. Its publishers deliberately removed portions of the biblical text, such as the Exodus story, that could inspire hope for liberation. Instead, the publishers emphasized portions that justified and fortified the system of slavery that was so vital to the British Empire.[1] ”

The Museum’s hope for the exhibit as stated by Anthony Schmidt, associate curator of Bible and Religion in America at the museum, is that “people take away a greater appreciation for that and maybe even a self-reflection to be more cognizant of why you read something a certain way . . . If people can better appreciate that then maybe they can better empathize with others.”[2]

While this goal is noble and much needed in interpreting the world today, the so-called Slave Bible may not be the best object for such a lesson. It is well known that religion throughout history has been used to give hope as well as to crush it. The Bible has been used to condone odious social practices such as colonialism and slavery. This fact is not to be overlooked. At first glance, the Slave Bible seems to be a product of its pre-abolitionist society. Its chief aim was to educate slaves in matters of the Christian faith, but its sub-textual intention was to discourage revolt and uprisings. As mentioned, this can be see through the careful selection of the biblical texts that form the heavily redacted book. Yet, is this the only way to interpret the data?

It is very difficult to deduce editorial intent here as there may be many reasons why certain texts were left out of a work. It may have some political intention, or they simply ran out of room. A fitting example comes from the canonization process of the Bible in the early centuries of Christianity. Other gospels and letters were left out of the canon that forms the Bible today. The reasons often were theological, ie. they did not align with orthodox faith. Yet, this does not mean that these gospels were legitimate and that there was a radical conspiracy to suppress dissonant voices. Some of them were just too bizarre.

Within the canon itself, there are many instances of editorial activity. The authors/editors who were organizing the history of Israel’s monarchy represented in Samuel and Kings often left out many details. Again, there are many reasons why they might have done so. It does not infer that they were necessarily trying to suppress marginalized voices or legitimate a particular monarch. There might be some residue of either of these intentions left in the text, but that does not mean that these residual intentions make up the main intention. The same may be true with regard to the Slave Bible. My goal is to provide a much richer analysis of the Slave Bible that will hopefully show that this sub-textual intention to justify and support slavery is not as pronounced as is thought.

The Text’s Origins and Context

The Slave Bible was originally published in 1807 under the name “Select Parts of the Holy Bible For the Use of the Negro Slaves, in the British West-India Islands.” It was printed in London by Law and Gilbert. These printers were responsible for printing much of the literature produced by the Society for the Conversion and Religious Instruction and Education of the Negroe Slaves in the British West India Islands (They loved long names back then). This Society was founded by the Bishop of London Beilby Porteus in 1794. Porteus had made a name for himself in 1783 by preaching to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), of which he was a member. [3] His sermon encourages Abolition (to a relative degree) and demands that Christians offer kind treatment of the slaves, especially at SPG’s own plantation on Barbados. Throughout his career, Porteus continually advocated for the end of the slave trade. By today’s standards, his views were not radical enough, yet they form part of the trajectory toward full abolition in 1833. It was Porteus’ society that produced the so-called Slave Bible.

Another piece of the puzzle is the social condition in the British controlled Caribbean. Historian Robert Smith notes that the slaves were not evangelized as part of the colonization process. It was only towards the latter half of the 18th century that concern for the slave’s religious experience was considered.[4] There were a series of laws passed in various colonies in the early 1800’s aimed at limiting education among slaves. These laws stemmed from the fear that slave education would endanger the “peace and safety” of the colonies. After all, the French colony of Haiti had been liberated through a massive slave revolt only a few years earlier in 1804. The Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed in 1807 which was another step of progress towards full abolition in the West Indies in 1833. Although trafficking in the Caribbean continued for another few years, it was nevertheless illegal. The Slave Bible enters into a new period of colonial history. Despite the relative victory of abolition, plantation owners are still leery about educating slaves. Yet, the Anglican Church now had a renewed and focused interest in evangelism and education among the slaves of their colonies.

The Contents of the Slave Bible

The Slave Bible contains selections of 14 books out of the 66 books that make up the protestant canon. This equates to roughly 10% of the Old Testament and almost 50% of the New Testament. Apart from one exception, the editors of the Slave Bible preferred to include whole chapters. As far as I can tell, they did not redact individual sentences or words they found troubling. We will explore this more below. Here is a list of exactly which parts of the Bible the Slave Bible contains:

Old Testament

Genesis 1-3; 6-8; 18; 37; 39-45

Exodus 19-20

Deuteronomy 4-6; 8-11; 28

1 Samuel 17; 24

1 Kings 3; 8; 17-18; 21

2 Kings 4-5

1 Chronicles 17

Job 1-3; 38-39; 42

Proverbs 1-24 [Missing 25-31]

Ecclesiastes [whole book]

Isaiah 1; 5; 9:1-7; 11; 14; 40-42; 44-45; 47; 51; 53; 55; 58; 60-61

Daniel 1-9 [Missing 10-12]

Hosea 6; 11; 14

Joel 1-2 [missing 3]

New Testament

Matthew [Whole book]

Luke [Whole Book]

John 4-5; 11; 13; 19; 21

Acts [ Whole book}

Romans 12-13

1 Corinthians 1-3; 13; 15

2 Corinthians 4-5

Galatians 1; 5-6

Ephesians 4-6

Philippians 2; 4

1 Thessalonians 4-5

1 Timothy 1-2

2 Timothy 2-4

Titus 2-3

Hebrews 1-3; 12-13

James 1; 3; 5

1 Peter [Whole Book]

1 John 3

The Text of the Slave Bible

It is hard to pin down the exact edition of the King James Version (or Authorised Version) the editors used. While the words are the same, the punctuation, capitalization, chapter summaries, and titles look different from most versions. Now, these variations do not affect the meaning per se. Most of the time the difference is between a colon and a semi-colon or the presence or absence of a comma. Other differences are more significant, like the editors’ choice to include the shorter chapter summaries found in some editions. Long chapter summaries, usually 4-5 points, can be found in the original 1611 KJV. These were later shortened to 1-3 points in other major versions. One version, the 1800 London – Corrall, leaves out the summaries altogether. The 1769 Oxford edition by Blayney became a sort of standard for the King James Bible (This is the edition modern KJV editions follow). In this version, the chapter summaries were lengthened, but differ slightly from the 1611 KJV. All this to say, there was a range of options for the editors to choose from.

Another example of a variation can be found in Mark 1:21, 25. The Slave Bible’s normal capitalization of “Jesus” is odd. Although represented in the 1611 KJV, most versions from 1760-1800, have Jesus in all caps (JESUS). The exceptions are 1800 London – Corrall which has only 1:21 in all caps, and the 1800 Oxford – Lawson that has 1:25 in all caps. Yet, these versions also contain many other differences. It was difficult to find a British Bible printed in the years between 1800 and the publication of the Slave Bible. I was, however, able to find a Bible printed in 1812 known as the Brown’s Bible. This work retains the standard JESUS, which implies that more than likely, the standard text had not changed in the previous decade.[5]

What can these variations tell us about the editors of the Slave Bible? First, these variations tell us that they did not simply “copy & paste” an existing edition of the Authorized Version and then remove the texts they found troubling. It appears that there was some intentionality as to how their edition would read by their use of multiple editions to create their composite edition. Now, it may be that these editors were simply careless in their printing, but this is unlikely due to the nature of printing at the time. The way the editors added or changed conventional punctuation seems to suggest that there was a reason behind it. We can only guess what this reason may have been. My take is that while they were not always effective, the editors attempted to improve the readability of the text for educational purposes.

The Counter-Intuitive Redactional Strategy of the Slave Bible

When looking at the table of contents above, I find myself puzzled by the editors’ choices. Following the Museum of the Bible’s hypothesis, it would make sense to exclude the account of the exodus and any mention of liberation. It would also then make sense to highlight obedience as well as the consequences for disobedience. Finally, it would be expected that the editors include passages that seem to support slavery. Yet, contrary to this theory, the Slave Bible defies these expectations.

While the editors have removed the exodus account where God delivered Israel from oppression, so have they also removed almost all of Exodus. The Slave Bible only includes Exodus 19-20 which recounts how Israel received the Law at Sinai and the 10 Commandments. Interestingly, in Exodus 20:2 it says, “I am the LORD thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage”. This is obviously in reference to the preceding narrative of the exodus. So why would the editors leave this in?

But this is not the only example. The editors also left in more than a dozen references to the exodus.[6] In addition to this, they also leave in plenty of verses that would appear to contradict the editors alleged pro-slavery intentions. Verses such as, “Is not this the fast that I have chosen? to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free, and that ye break every yoke?” (Isaiah 58:6). They included 1 Timothy 1:10 which condemns “men stealers.” They included most of the book of Daniel which features multiple stories of civil disobedience against the Empire. They even left in Luke 4:17-20 and Isaiah 61 which not only depicts the liberation of the oppressed but was even used by Beilby Porteus and others to argue for abolition!

The editors also left out a lot of passages that would be helpful in defending slavery. It would have made a lot of sense to include the story of Hagar – a text often cited to support slavery. The Hagar narrative could indeed be seen to legitimate cruel treatment of slaves as well as rape and concubinage. This narrative is referenced by Paul in Galatians 4 as a (confusing) metaphor for Israel, “Nevertheless what saith the scripture? Cast out the bondwoman and her son: for the son of the bondwoman shall not be heir with the son of the freewoman. So then, brethren, we are not children of the bondwoman, but of the free” (Galatians 4:30-31). Surprisingly, both of these texts are missing from the Slave Bible. Instead, the editors included Genesis 18 which includes Abraham pleading with God to spare Sodom and Gomorrah as well as Galatians 5 which begins, “Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free, and be not entangled again with the yoke of bondage.” Even the inclusion of the Joseph narrative is problematic for the pro-slavery view. Although the story recounts how Joseph prospered despite being a slave, the story also reveals the vileness of slavery and the treachery of evil masters. At the end of the story, Joseph has become in charge of the kingdom, second only to the king, being exalted over his former master and his brothers who sold him into slavery.

Much has been made of the exclusion of certain passages that specifically speak to ending oppression. Writing for the Smithsonian, Brigit Katz notes, “Gone was Jeremiah 22:13: “Woe unto him that buildeth his house by unrighteousness, and his chambers by wrong; that useth his neighbour’s service without wages and giveth him not for his work.” Exodus 21:16—“And he that stealeth a man, and selleth him, or if he be found in his hand, he shall surely be put to death”—was also excised.” This comment makes it seem as if only those verses were excluded from a wider context when in reality, the whole book of Jeremiah was excluded as was every other casuistic law. Others have noted that the exclusion of Revelation suggests that the editors wanted to leave out any mention of the new creation i.e. the end of all evil and oppression. Yet, they fail to mention the inclusion of 1 Thessalonians 4-5, among others, which speak of Christ’s second coming. If the only reason for these redactions was to remove pro-liberation elements, then why are entire books missing? Surely, not everything within these books fit the criteria of being pro-liberation.

At first glance, the Slave Bible’s including of many passages that refer to obedience and humility seems to support the alleged pro-slavery intentions. For example, the Slave Bible includes Romans 13:1 (“Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers”), and Ephesians 6:5 (Bondservants, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, with a sincere heart, as you would Christ). Again, these verses do not stand by themselves. Not only is the whole chapter included, but also preceding chapter in both of these cases. Within these chapters, the clear emphasis is on the proper actions of a Christian. The rest of Ephesians 6 details the proper relationships between children and parents as well as slaves and masters. “And, ye masters, do the same things unto them, forbearing threatening: knowing that your Master also is in heaven; neither is there respect of persons with him” (Eph. 6:9). This would have been just as radical in the 19th century as it was in the 1st. The book finishes by describing the nature of spiritual warfare and the Christians defenses against it. To Paul and the other New Testament writers, these exhortations are the natural outworkings of the gospel. There is a definite shape to the Christian life, and obedient humility is one of the many characteristics of a follower of Jesus.

Conclusion

The Museum of the Bible’s hypothesis about the redactional strategy of the editors to support slavery and encourage subservience is certainly coherent. We can imagine a bunch of people deviously devising and crafting a book that would secure their power and maintain their control over others. We can imagine this because it has happened countless times throughout history. Yet, this hypothesis is not plausible according to the data. If one does hold to this position they will be forced to concede that the editors were either sloppy or unintelligent in their redaction process. That, or they had the worst printer ever.

I do not wish to whitewash history, to make the editors of this redacted text champions of abolition. They were not. Slavery was and is evil. Simply “treating slaves kindly” was and is not enough. From our position in history, we know that these editors and the society to which they belonged were far from honorable. Yet, they were on the right path. Thus, I do not believe they intentionally redacted the biblical text to discourage revolt or support slavery. There are many other examples of such an approach that we may turn to discuss the dark side of the Bible’s reception. I believe that the primary and most apparent intentions of the editors of the Slave Bible were educational and evangelistic.

We see this in the Christological shape of their redaction. The only time these editors included part of a chapter, as opposed to the whole thing, is found in Isaiah 9:1-7 which records a messianic prophecy. This text is echoed throughout the New Testament and is seen to be in reference to Jesus. The chapter summaries included also support this Christological emphasis as parts of the Old Testament are described as speaking of Christ and the gospel. The rest of the included Isaiah portions, as well as the selections from Hosea and Joel, are equally messianic and tell of the day when God would send a deliverer to save his people. While the Slave Bible only contains 50% of the New Testament, it does contain nearly the whole of the actual narrative of Jesus’ life and the formation of the early church. Perhaps the editors were more concerned to communicate the gospel’s story of Christianity rather than the theological reasoning found in Paul. The Slave Bible also emphasizes the value of wisdom and proper Christian living. It includes the main sections of Job, much of Proverbs, and the whole of Ecclesiastes. Much to the chagrin of modern pastors, the editors did not include the theologically dense sections of Paul’s letters, choosing to focus instead on the more universal calls to holiness, righteousness, and Christian love.

I am thankful the Museum of the Bible has chosen to display this book. It has begun a discussion concerning how our cultural values often distort our reading of the Bible. There is no doubt that the editors of the Slave Bible were influenced by their culture’s practice of slavery. I think that the discussion must turn away from the simple reasoning offered by the exhibit and focus on how slavery continued to function in light of the pro-liberation emphasis of the Bible. It would be interesting to explore how the Church during the 18th and 19th centuries justified slavery using these selected texts. Another line of inquiry could focus on why the exodus was not central to a distillation of the Bible, and what that might say about white readings of biblical narratives that feature slavery. Interpreters of the Bible lie on both sides of the abolition debate, and the cruelty of slavery was prolonged by poor readings of Scripture. In our time, in our own contexts, we must learn from the blunders and atrocities committed by our ancestors and be aware of how our culture and experience has influenced us in perpetuating injustice.

** The text of the 1807 Slave Bible can be found here **

[1] https://www.museumofthebible.org/exhibits/slave-bible

[2] https://www.npr.org/2018/12/09/674995075/slave-bible-from-the-1800s-omitted-key-passages-that-could-incite-rebellion

[3] Porteus, Beilby. A sermon preached before the Incorporated Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts; at their anniversary meeting in the parish church of St. Mary-le-Bow, on Friday February 21, 1783. By the Right Reverend Father in God, Beilby Lord Bishop of Chester. London, MDCCLXXXIII. [1783]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online. Gale. Durham University. 9 Jan. 2019. <http://find.galegroup.com.ezphost.dur.ac.uk/ecco/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=ECCO&userGroupName=duruni&tabID=T001&docId=CW3323399405&type=multipage&contentSet=ECCOArticles&version=1.0&docLevel=FASCIMILE>.

[4] Smith, Robert Worthington. “Slavery and Christianity in the British West Indies.” Church History 19, no. 3 (1950): 171-86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3161292.

[5] I tried very hard to find an edition printed in England between 1800-1807, but I was unable to on the databases to which I had access. There very well may be some edition lurking out there that matches the Slave Bible exactly. Even so, it still would not match the 1769 Oxford which had become a sort of standard.

[6] Deuteronomy 4:20, 32-40; 5:6, 15; 6:12, 21; 8:14; 9:26; 11:3. 1 Kings 8:9, 16, 21, 51-53; Isaiah 11:16; Daniel 9:15; Hosea 11:1; Acts 7:34-39; 13:17.

3 Comments

Leave your reply.