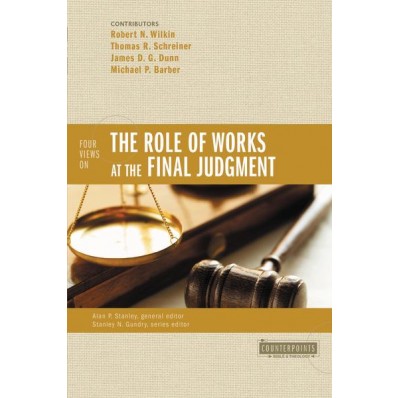

“The Role of Works at the Final Judgement,” edited by Alan Stanley admirably expands Zondervan’s “Counterpoints” series. For those unfamiliar with the series, these volumes bring together divergent viewpoints and place them in direct dialogue. Here, four different views on the title subject are represented by Robert N. Wilkin, Thomas Schriener, James D. G. Dunn, and Michael P. Barber. Each presents an essay which is followed in turn by a response from the others. This proves a very effective way at giving each an individual voice both in support of their position and in response to others. Stanley provides a very helpful introduction to the subject, especially in relation to contemporary debates, and a useful summary in conclusion.

First, Robert N. Wilkin argues that works play no role in the final judgment of a believer, defined as one who has professed faith in Christ. Wilkin’s interpretation of John 5.27 is the controlling center of his thought, and comes up in every one of his responses to other views. Wilkin admits that there are many passages of scripture that seem to say otherwise, but he argues that these are not relevant to the question for two reasons. First, “salvation” can refer to deliverance from temporal calamities (physical death, the Great Tribulation, etc.). Second, Wilkin’s eschatology includes two judgments. In the first, only Christians are judged, according to their works, and rewards are at stake not eternal salvation. The second judgment is the Great White Throne, and believers will not be judged at that time. He concludes,

We rejoice in this security. Let us not go through life fearful of the final judgment. Believers will not be judged there. (50)

Second, Thomas R. Schreiner argues that works, including perseverance, are necessary for final salvation, but these arise inevitably as a result of true faith. This does not mean that the works themselves are meritorious and thus contribute to salvation is some kind of economic sense. Initial justification is by faith alone, and with that declaration of innocence the believer begins a life within the New Covenant: Spirit-filled, Spirit enabled obedience. Salvation is a process as well as an assured state. He summarizes,

Hence, works constitute the necessary evidence or fruit of one’s new life in Christ. We can say that salvation and justification are through faith alone, but such faith is living and vital and always produces works. (98)

Third, James D. G. Dunn argues that the New Testament is not systematic theology, and so we should not expect that the authors will be consistent with each other or indeed themselves. Thus, Dunn can conclude that the New Testament appears to teach that final salvation is by both faith and works, and putting them together coherently, systematically, or logically does violence to the texts. Dunn is keen to affirm human responsibility in such a way that it is not obliterated by divine action, even if that action is described as enabling or empowering. Dunn explains the tension in terms of the occasional nature of the New Testament. When Paul (or other authors) encountered a specific situation he responded in kind; these responses taken together are not uniform. His final word:

Is it so serious that we cannot fit the two neatly into a single coherent proposition? Is it not more important that we should hear both and respond to both as our situations and (dis)obedience of faith require? (141)

Fourth, Michael P. Barber seeks to present “the official teaching of the [Roman] Catholic Church” (162 n4.). Accordingly, he argues that works are meritorious for final salvation, but are only so because of the grace of God. Grace is such that it can do the impossible: make human works meritorious. Thus, the accumulation of good works is necessary for meriting or earning final salvation. Barber, like Schreiner, also understands salvation as a process, but significantly differs from him in that final salvation is not assured. Within this scheme the Church plays a key role, “no one can save themselves by their own actions performed independently of God or the believing community of the Church.” (182) Baptism is but one example of such an action, “For Catholics, baptism is truly a saving event.” (183) It must be underscored that for Barber grace is always primary. By grace, the believer is able to earn final salvation by their works. In his conclusion Barber writes,

Protestants may disagree with the Catholic understanding, but let it not be said that this is because Catholics have a low estimation of grace. To say the Catholic view is incorrect is to say Catholics attribute too much to grace. (184)

Each one of these views is supported by numerous biblical texts, each of which are marshalled by different authors to support different conclusions. Such is the case with any debate over doctrine that is biblically based. The brevity of each essay makes thorough, detailed exegesis impossible, but it is still possible to get a grasp of each author’s particular approach. It seems that the source of disagreement is actually located the key presuppositions of each position.

For Wilkins, Dispensationalist eschatology and John’s gospel, set the course. Schreiner works under that assumption that the scriptures alone provide the answer, and that a coherent answer can be found therein. Dunn approaches each book of the NT as distinct, and makes little effort to harmonise various passages because they resist systemization. Barber begins his article by quoting the Catechism of Catholic Church, and is clearly constrained by those magisterial conclusions. What they each share, however, is a pastoral concern that the scriptures be accurately and faithfully interpreted, and that they are the source of true Christian doctrine. For this reason, even while debate is inevitable it is possible to engage with each other charitably and with the actual possibility of constructive dialogue. On this point, the interactions between Schreiner and Barber are particularly helpful in clarifying where Protestants and Catholics, broadly speaking, can stand on common ground but also where significant disagreement prevails.

One shortcoming of the book is that it is obviously modelled on a “Eurocentric” understanding of Christianity. It would have been quite informative to bring a voice or two from other traditions into the conversation. How is this particular issue dealt with in the Orthodox tradition or other congregations located outside the scope of western traditions?

The Bottom Line: Four Views on the Role of Works at the Final Judgment presents just that, and is admirably introduced and concluded by Stanley’s helpful analysis.

Review by Raymond Morehouse (remorehouse@gmail.com)

University of St. Andrews

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.