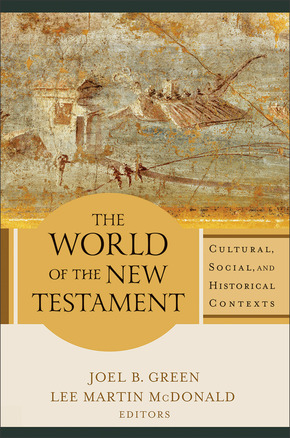

The World of the New Testament (WNT) is a reference work covering a wide range of topics relating the historical background of the New Testament (NT). The volume is divided into forty seven entries contributed thirty four scholars. Entries vary in length, the shortest is only four pages while the longest is twenty one; the average length of each entry is around ten pages. A complete table of contents and list of contributors can be found here. Green and McDonald have pulled together an outstanding group of scholars and the reader will find many recognizable names among this list. The volume also includes an introduction and glossary by the editors. This collection is further supplemented by over seventy illustrations and seventeen maps.

The volume is divided into five parts. The first two parts make up a section entitled “Setting the Context” which consists of “Exile and Jewish Heritage” and “Roman Hellenism”. The subjects in these parts are more global in character. Part three is entitled “The Jewish People in the Context of Roman Hellenism” and covers more particular topics than the previous two. Part four covers “The Literary Context of Early Christianity,” and includes essays on major literary works and figures that have bearing on the NT. The final part is “The Geographical Context of the New Testament” and covers the major relevant geographic regions.

Space does not allow a complete summary of each entry, but some general remarks will be helpful. WNT is best described as falling somewhere between a bible dictionary and a collection of essays. Material is not arranged alphabetically, nor is the volume intended to contain a comprehensive array of topics as in a dictionary. On the other hand, the entries’ length and character preclude them from being taken as essays. For this reason I have opted to refer to the contributions as entries rather than essays or articles. The primary purpose of each is to convey basic information rather than present a sustained argument or advance a novel thesis. Each entry is introductory in nature and therefore quite accessible for the lay-reader. Each also includes an individual bibliography which also includes short (usually one sentence) summaries the cited work. Entries are generally written from and for a Christian context and the biblical text is therefore generally regarded as a trustworthy source of historical data, though this may vary from entry to entry.

Many of the entries in this volume will be quite helpful, and accomplish what they set out to do (Nicholas Perrin and Lynn H. Cohick’s contributions come immediately to mind). At their best, an entry provides enough introductory information to satisfy the casual reader but also excite the student to continue their study. James Charlesworth’s entry on NT archaeology is a shining example of this. Charlesworth weighs the pros and cons of using archaeology to inform our NT understanding, and cites numerous examples where such information is useful. (His comment, “…for nearly two thousand years ecclesiastical leaders have attempted to establish that Christian faith is not focused on a far-off celestial Christ. It is grounded in an incarnational theology and the world in which all humans live from womb to tomb.” (463), neatly summarizes the admirable goals of the volume.)

Nevertheless, the volume is marred by the presence of personal biases in some entries that are jarringly obvious and particularly misleading. For example, in an entry intended to cover “Civic and Voluntary Associations in the Greco-Roman World” Michael S. Moore writes, “Following the death of Alexander [the Great], his generals create pyramidical, inefficient, sycophantic, and highly corruptible regimes as the empire-versus-city polarity slowly replaces the autarkēs ideal of the old Greek polis.” (152) He goes on to describe the Roman system as “imperialistic tyranny” and a bureaucracy which “oppressively taxes the populace to fund the building of gaudy religious temples dedicated to the deification of the latest patrician emperor.” (ibid.) Such a construal may have a place in a different context, but here can only be regarded as misleading. Moore is entitled to his artistic or political sensibilities, but is it relevant for reader to know that his tastes don’t include Greco-Roman architecture or that he is irritated with bureaucrats? Unfortunately Moore is not alone in including this kind of misleading personal commentary. Another example is S. Scott Bartchy’s description of all Roman slaves as de-humanized chattel but who were neither at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid nor a class without significantly powerful individuals (esp. the familia Caesaris) is ultimately incoherent. In his attempt to portray first-century slavery as an unqualified evil Bartchy ignores counter-evidence even as he presents it. Simplification is necessary in a reference volume, but over-simplification is disastrous.

Unfortunately these biased entries make WNT, taken as a whole, unsuitable as an introductory volume. Readers who are already familiar with the complexities of historical work generally and the first century in particular will be able to sift and detect oversimplifications of the sort evidenced above. But that will not be the case, for instance, with a class of undergraduates or lay-readers. Bright lights, however, still shine through and those readers willing to work through the material will be rewarded. For the educator, WNT may provide a valuable source of selected readings. Additionally, the short summaries included in each bibliography are a very helpful starting point for further study.

The Bottom Line: WNT functions best as a reference work designed to introduce readers to the historical background of the NT. While the volume contains many strong entries it is marred by the presence of misleading simplifications of complex issues.

Review by Raymond Morehouse (remorehouse@gmail.com)

University of St Andrews

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.