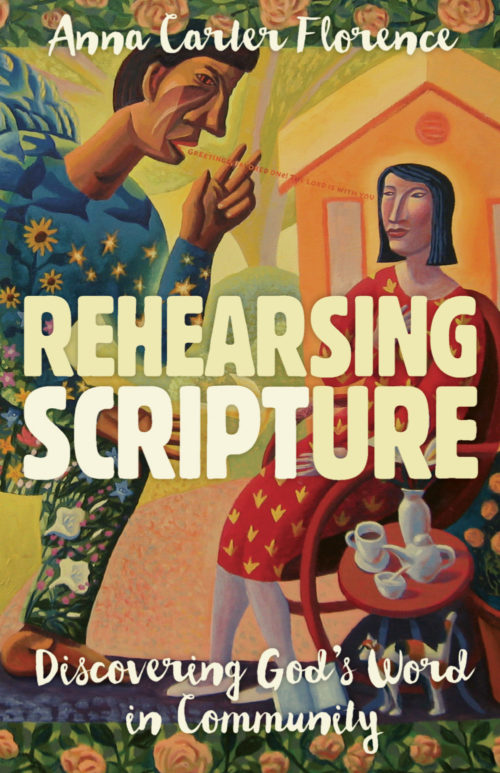

Anna Carter Florence

Rehearsing Scripture: Discovering God’s Word in Community

Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2018.

Pp. 215, paperback, $16.99 ISBN 9780802874122.

In Rehearsing Scripture, Rev. Dr. Anna Carter Florence (Peter Marshall Professor of Preaching at Columbia Theological Seminary) offers a compelling vision for how the Church can read scripture afresh by adopting it as a script for performance. With personal examples and biblical commentary, Florence encourages her readers to join the “Repertory Church,” a place where those who wish to hear God can rehearse his Script in someone’s living room before performing it in their daily life. Authoritative, yet approachable, the author gives instructions on how to pay close attention to the text, especially how to “read the verbs,” so that one may find something true to say. While many great things can be gleaned from this book, here are my three main takeaways:

The Importance of Communal Reading

A central metaphor in this book is the “Repertory Church.” Similar to a repertory company which is a small group of actors that frequently perform together, the Repertory Church is a small group of readers who come together to perform the text. It is in these contexts that we as readers can understand the richness and breadth of scripture. So often we can become stuck in our own way of looking at a story or a portion of the Bible. It takes a community to fully understand what is going on. Relating her own group experiences, she writes, “We saw that the script is so deep that there is always another way to play it, and always another way to read it. And that different casts of players can show you different sides of a scene, and you don’t have to decide which one was right or better or even definitive—just which moments were true” (11). While reading and studying the Bible is important and necessary, getting together with others can offer different perspectives that we need to hear.

The Benefit of Performing Scripture

One of my favorite moments in the book was Florence’s reading of Genesis 3:7-8. She carefully works through the main verbs in these verses and discusses them at length. What was particularly illuminating was her recounting the time she tried to reenact it. She explains that it took her students over an hour to sew a loincloth out of fig leaves, and the end product was laughably ineffective. She writes,

Sometimes it takes a literal reenactment of the verbs to show you what’s really going on. In this text, it’s the fig leaves that get most of the attention, as nouns often do. They’re glossy and showy and provacatively placed, and so well knwn that they’ve become their own figure of speech. But the text gives us a verb to go with ‘fig leaves,’ and that takes the image in a completely different direction. Now, they’re more than a cover-up. They’re evidence of the futility and absurdity of the whole concealment enterprise (26).

This is a brilliant example of how performing a text can aide our interpretation of the biblical text. By simply asking the question, “how would I play this part?”, readers can learn something new and special about the text, something that a basic commentary might not teach you.

The Relief of Rehearsal

A theme that runs through this book is that when the repertory church gets together it rehearses the text in order to perform it later in the real world. “Rehearsal is a place to experiment, to try out many possible interpretations of a text. Then we can decide how we want to perform it” (12). Thus, when we gather in our small groups we don’t need to have all the right answers. One of my chief frustrations in any bible study is those minutes of awkward silence after the leader asks what’s going on in the text—it’s as if everyone has forgotten how to read and speak! The reason for the let-me-keep-my-head-down-and-pretend-to-stare-at-the-text-so-no-one-will-call-on-me tactic we learned in grade school is because everyone is afraid of being wrong. What this book reminds us is not that there are no wrong answers, but that in rehearsal, we are all learning together how we ought to play our parts. A recurring reference is to Where the Wild Things Are, an apt example of the aim of these group explorations: “You’re looking to come back with a word of truth—a Word from the Lord. But only after you’ve had a good rumpus” (13).

Readers of all types could benefit from this book. What it lacks in explicit hermeneutical theory (no doubt a strategic choice by the author), it makes up in its extremely practical application. Filled with helpful insights and practical guides, any participant or leader in a small group or bible study could learn immensely from this book.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.