We’re Getting Christmas Wrong

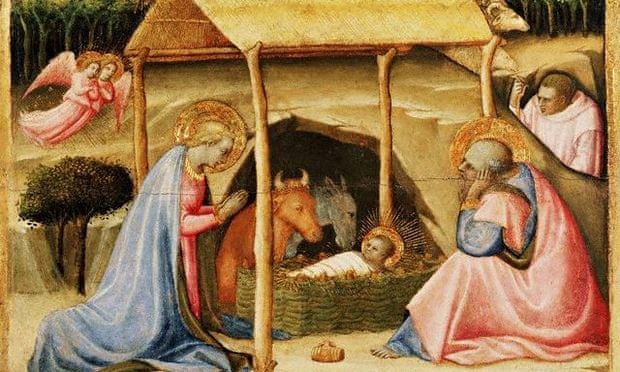

Over the past few Christmases, I’m noticing an uptick in blog posts and essays about how Christians are “getting Christmas wrong,” that our old quaint stories about Jesus being born in an animal stable are historically implausible, and that our hymns and advent traditions are being “spoiled” by eminent historians who are at last able to redirect our wrong-headed traditions by breaking in new shafts of light from the historical insights of the past.

None of this is to criticize such corrections. After all, we (myself included) tend to like it when our pastors and teachers expand our minds, blow up dry and staid paradigms, or challenge lazy thinking about God and Scripture. And I still remain convinced that some of our most important insights in Scriptural interpretation come from a deeper appreciation of the historical world of the Old and New Testament.

My concern, however, is when this mode of engagement dominates our primary mode of scriptural exchange. When this happens, we begin expecting our pastors and teachers to “pull back the curtain” every time they teach on a text.

“Too many people interpret this passage as being about thing ‘Y,’” we might hear our favorite teachers explain. “But I’m here to tell you that this passage is actually about neither ‘X’ nor ‘Y,’ but the hidden thing ‘Z,’ that thing you didn’t know about because you can’t follow the original Aramaic, or because you’re not familiar with Ancient Stoic cosmology.”

When this mode of expositing Scripture becomes entrenched as the norm, we end up (perhaps imperceptibly) turning our pastors and teachers into gurus—necessary experts on the Bible who serve to broker the text for us, decoding the deeper truths lying beneath the text’s foreign historicity and translations.

When the Questions Really Do Mean More Than the Answers

But there are other ways of talking about Scripture that do not always involve the monological dynamics of an expert teaching others to get the text “right.” Reading through the gospels again this Christmas season, I’m constantly struck by how much of Jesus’s own instruction was accomplished from the questions of his followers. And as a sure sign of a good teacher, even ‘bad’ or ‘silly’ questions managed to sneak their way through.

– “So, uh, Jesus, who’s greatest in the kingdom? It’s me right?” (Mt 18:1)

– “Dear Rabbi… Can my sons sit at your right and your left hand when the kingdom comes in glory?” (Mt 20:21)

– “My Lord, remember that town that treated us so badly? Can we, uh, you know, call down curses against them now?” (Lk 9:54). I could be wrong, but I picture Jesus glancing at the sky when he hears questions like these.

Other questions we find in Scripture, however, are much more interesting.

– “If we’re supposed to ‘love our neighbor,’ just who exactly is our neighbor?” (Lk 10:29); I could be wrong here too, but I picture Jesus smiling as he responds, “I’m glad you asked. Let me tell you a story.”

– Or another good question: “Good Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” (Mark 10:17)

– Still another good one: “How many times must I forgive my brother?” (Mt 18:21).

More often than not, Jesus taught with his hearer’s questions in mind. Furthermore, the “answers,” were never quite satisfying—never the kind of answer that settles matters definitively. Rather, Jesus’s answers carried a disquieting sense with them; they were never fully the way we would want him to phrase things; and they were, in every instance, an invitation for further discussion and reflection.

Leaving Room for Conversations

When our pastors and teachers broker the text for their students and congregations as a guru would to eager audiences, what is often received is performance and the finality of resolution. And perhaps sadly, what is often gained is the elevation and admiration of a brilliant teacher. By contrast, when our leaders also engage our churches from the standpoint of their own questions, and even better, from the standpoint of the questions presented within Scripture, what is often gained is conversation and participation. Questions are central precisely because they are necessarily participatory. When we ask one another “who is the ‘neighbor’ that we ought to love?” we can give our historical experts a break, and permit others in the room to weigh in with their wisdom and God-given experience. We allow admonishment and correction from those partnering members gifted enough and gentle enough to provide it. We also enable less vocal persons the space to reflect on the people in their own lives that God might be prompting them to love.

And perhaps most importantly, when we invite a conversation prompted by our earnest (and even potentially foolish) questions about God, and when we ask the very questions along with those asked in the Bible, we allow ourselves space to confront Jesus in the Scriptures. Our concern becomes not getting the text right so much as it is meeting the living God in the Jesus that the text points us to. Yes, reading the text rightly is also important, but above that, Jesus says it best: “These are the Scriptures that testify about me” (John 5:39). And when these questions lead to more questions, or lead to discomfiting responses that don’t sit quite sit well, or even lead to invitations for further discussion and reflection, we can be assured that we are getting close to confronting Jesus as he is revealed in the text—the kind of Jesus that won’t cooperate with easy answers or be adequately summed up in a sermon of three points. Meeting Jesus in Scripture together lends itself more naturally in the dynamics of group question and exchange. When we do this more often in our gatherings together, we can be assured that we are not expecting to simply master the text, but rather aim to be mastered by it.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.