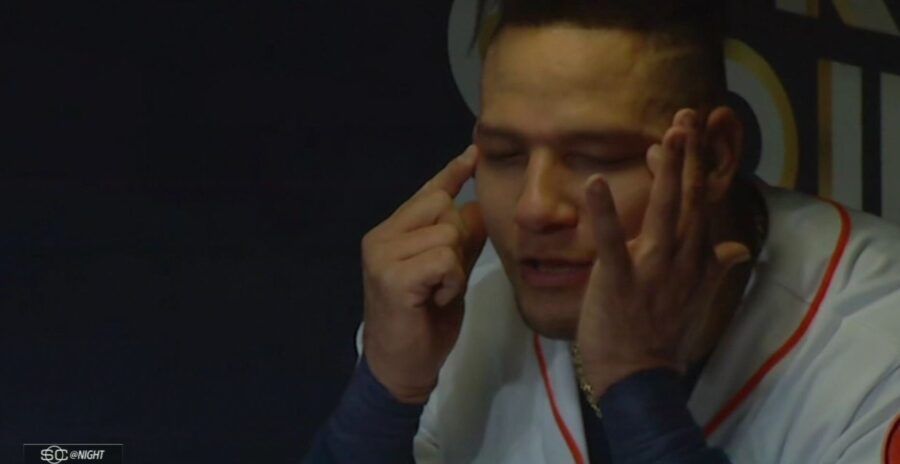

If you have been watching the World Series, or have simply been online this week, you may have seen the storm that arose after Yuli Gurriel of the Houston Astros rubbed in a home-run off Iranian-Japanese pitcher, Yu Darvish, by slanting his eyes up and referring to him as “Chinito” [Little Chinese Guy].

People of the internet, as you might imagine, took sides. Many deemed the gesture disgraceful and worthy of suspension from the remainder of the World Series. Others (not a few Houston Astros fans) defended the act as relatively less offensive in Gurriel’s own cultural context. Sadly, some just cheered the actions because, you know, racism.

omg @astros .. you guys have the best fans. #RACISTTEAM pic.twitter.com/L0fSxth5N4

— ♡ (@feSOUL) October 30, 2017

As an Asian who has had to deal with this kind of childish mockery his whole life (still do), and has had to see my children face similar taunts in their own Little League games, I was offended. As a Dodgers fan who ended up seeing the Dodgers lose that game, my offense morphed into outrage.

I hurried my wife over to my laptop to show her the offending GIF. You know the one.

“Look at this!” Unable to come up with anything else clever on the fly, I remember saying something unimaginative like, “What is he, like … 4?” [Always a devastating take-down, when you’re like, 4]. My wife casually agreed that it was childish and offensive, but then she gave me a look. I know that look. I knew what she was thinking even if she didn’t say it out loud. Her eyes said something only she and I would understand. They said,

“What about Pau Gasol?”

For context, you would have to understand that she knows that I love Pau Gasol. And I do. Pau used to play for the LA Lakers (another team I root for). He has unique athletic gifts for his 7-ft frame and played a beautiful game in his prime. He was a former medical student before becoming a pro-player. I like that he still stays current with medical practice as a player. I like that he plays the piano. I like that he quietly does his charitable work without the presence of cameras, the press, or personal foundations. I’ve met Pau once and he handed me a t-shirt (an oversized t-shirt that my wife knows I wear more often than I should).

But Pau Gasol also was pictured doing this during the Beijing Olympics.

Gasp. Just like Yuli Gurriel (without the “Chinito” remark). She knows I’ve made excuses for Pau in the past. Oh that? Pau was doing this as part of a team photo. Pau would never do this acting alone. Come on, that’s just … you know, he didn’t want to spoil the team atmosphere by not participating. There’s cultural differences at work, see? You take all of those responses together, and I start to sound like Houston Astros fans who are defending their own guy (Gurriel), contextualizing his response without necessarily condoning or normalizing it.¹

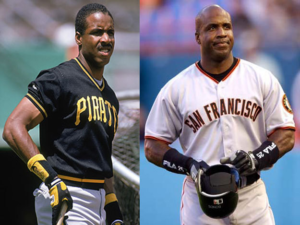

It is in sports where rooting interests and fandom expose these double standards most nakedly. An easy example is Barry Bonds.

Bonds was one of the most unlikeable players in baseball history. He was arrogant, he was amazing, and he was clearly cheating by using performance-enhancing steroids—not even Giants fans could credibly deny it. But whenever Bonds would step up to the plate, the good fans of AT&T Park (formerly Pac-Bell Park) would stand up and cheer as if to say, “He may be a villain, but he’s our villain.” Incidentally, the day after Yuli Gurriel received the storm of criticism for his racist gesture, Houston Astros fans (at least those visible on TV) gave him a standing ovation at his first at-bat.

What Can We Learn?

Yu Darvish was magnanimous in his response to Gurriel’s (“I’m sorry if you were offended”) apology (more gracious than I, clearly). His response is worth reproducing here:

— ダルビッシュ有(Yu Darvish) (@faridyu) October 28, 2017

Darvish is right — the important thing is to get people together to learn something from this. We all react from somewhere. Same sides, however, go a long way in shaping our response. And that is my Yu Darvish takeaway lesson I am going to learn from all this. Same sides matter. People are much more willing to be forgiving to one of their own. The key thing lies in re-negotiating our commitments to taking sides; to widening the circle of people who are on your own side. Disavowing sides might be hard in sports, but potentially not as difficult elsewhere in life (Snowflakes/Deplorables; Red States/Blue States; People who leave 999+ unread email notifications on their phones and Everyone Else). You can do something about all of the outrage, offense, and voluble complaining on both sides of many kinds of debates. You don’t have to always choose a side. You can say “no” to all of this. You can say, “No” to the entrenchment. You can say “No” to the partisanship. You can have conversations that remain truly open to learning what other folks different from you have to say. The next time you’re finding yourself outraged over the latest thing on Twitter, perhaps it might help to ask yourself, “What About Pau Gasol?”

¹ Some of my friends have rightly explained that we must show caution in applying a trigger-sensitive American standard of racial offensiveness to other cultural and international contexts.

2 Comments

Leave your reply.