Having emerged from the bowels of Hell, Dante and his guide find themselves upon the shores of the fresh and uncharted territory of Purgatory, a mountain surrounded by sea and pure air free from the stench and darkness of the Inferno. From the opening lines of Purgatorio, the poet distinguishes this place as God-graced: the dawn spreading the “sweet color of eastern sapphire”—the color associated with the Virgin—across the skies welcomes the pilgrim to journey among the penitent souls by the light of the sun (1.13). Purgatory is a place of healing where souls, damaged and deformed by their former sins, are rehabilitated to the love of the good. As the pilgrim arrives upon the first terrace, the terrace designated to purging pride, Dante observes the penitents’ sufferings and witnesses how the terrace’s artistic features strengthen their desire of virtue. Furthermore, the pilgrim participates in purgation through analogous means; as the souls who circle the terrace see and hear the ruin of pride and the greatness of humility in the God-engraved images, so the pilgrim is drawn into this contemplation through his interaction with the penitent. In contrast to the pilgrim’s posture of humility, however, the poet must write with a “sanctified audacity”—riding along the edge of pride’s pitfalls without falling prey to presumption—in order to truly represent the pilgrim’s experience thereby enabling the reader to also participate in the sanctification through seeing and hearing in the poet’s own work.

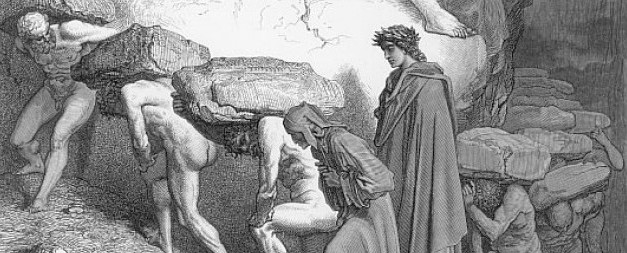

Upon each of the terraces of the mountain, the souls suffer the penitence proper to the sins which formerly dominated their souls. Those upon the terrace of pride, who in life refused to bend their stiff-necks, now bow low under great weights carried upon their backs. As the poet turns to introduce the penitential souls he interrupts himself saying: “But I do not with you, reader, to be dismayed in/ … when you hear how God/ wills that debt be paid.” (10.106-108) Indeed, the severity of the penitence is startling, but our poet advises his readers to “think/ what follows it, think that at worst it cannot go/ beyond the great Judgment” (10.110-111). Though the souls must endure pains, their sufferings differ dramatically from the torments of Hell in that their discomforts draw them nearer to healing– closer to standing upright without becoming puffed up and ascending the mountain without the weight of their sin impeding their progress.

Within each terrace of Purgatory, the souls also receive varying forms of encouragement to habituate the soul toward virtue and drive the soul from vice. In the terrace of pride, the penitent look upon images of the mighty who have been brought low imprinted upon the ground and mighty exemplars of humility carved into the mountain wall. Crouched under their burdens, the penitent pilgrims gaze upon images representing the destruction of the proud depicted upon the ground like graven medieval effigies until their desire for virtue grows strong enough to lift their eyes toward the statues exampling humility: the holy Virgin’s ‘yes,’ King David’s shameless dance before the ark of the covenant, and Emperor Trajan’s compassion for the widow. These representations fashioned by the finger of God, in which the “Dead seemed the dead, and the living living” so truly represent reality that “not only Polyclitus but even Nature/ would be put to scorn there” (12.67, 10.32-33). As the pilgrim passes along the images of humility, his perception moves beyond mere sight so that he “would have sworn” to hear the angel’s greeting and the Virgin’s reply or the choruses of Israel singing. By the time Dante reaches the final image depicting the widow appealing to Emperor Trajan, the images no longer merely seem to be speaking, but are in fact works of “visible speech” (10.95). While the effigies depicting examples of the proud do not produce the same sensory experience for the pilgrim they nonetheless demonstrates God’s high art which unites the ver and signum so that “one/ who saw the true event did not see better than I” (12.67-68). Upon this terrace, art, the experience of seeing and hearing, operates as a sanctifying force in the soul’s progress: the representations made by divine design reinforce the penitent’s rejection of pride and promote the love of humility.

Just as the penitent souls are spurred on toward virtue by the experience of seeing and hearing through the images which they contemplate, so the pilgrim participates in the purgation of the prideful through seeing the penitent and hearing them speak. Dante writes,

As to support a ceiling of a roof we sometimes

see for corbel a figure that touches knees to breast,

so that what is not real causes real discomfort to

be born in whoever see it: so I saw them to be,

when I looked carefully. (10.130-135)

In seeing the souls, which he compares to artistic features on a building, the pilgrim feels their burden within his own soul. Similar to the figures engraved upon the wall in which sound and speech are perceived, the pilgrim’s interaction with the souls includes the dimension of dialogue which further draws him into participating in their purgation. First among them is Omberto, a Tuscan, who, having prided his noble birth, must now “keep… [his] eyes/ turned down” under the strain of the stone upon his back (11.53-54). As the pilgrim listens to the soul’s story, the poet recalls how “I bent down my face” in imitation of the posture of the penitent proud (11.73). The pilgrim is then beckoned by Oderisi, “the honor of that art called/ illumination in Paris,” who speaks with Dante concerning pride– artist to artist (11.80-81). Not only does Oderisi now consider his artistic successors greater than himself, but he cries out against the folly of pride saying, “Oh vain glory of human powers! How briefly it/ stays green at the summit, if it is not followed by/ cruder ages!”; the artist’s fame like the “color of grass” lasts for moment until it fades and another outshines the last (11.91-93, 11.115). The pilgrim, receiving Oderisi’s warnings against prizing artistic superiority notes how the painter’s words take spiritual effect and “instill good/ humility in my heart, and you reduce a great/ swelling in me” (11.118-119). The pair continue to walk “Side by side, like oxen under a yoke” until the pilgrim’s guide directs him onward (12.1). By comparing their companionship to oxen sharing the same yoke, the poet reinforces the pilgrim’s participation in purgation through his interaction with the penitent placed there. When the pilgrim parts from Oderisi, Dante’s posture shifts from bowing low, the position he took when walking along Omberto and Oderisi, to standing upright (12.7). Though the pilgrim returns to standing physically erect, Dante tells the reader that “in thought I remained bent over and/ humbled” (12.8-9). Through the pilgrim’s interaction with the souls circling the terrace– seeing them first from a distance and then hearing them speak, Dante is drawn into the process of purgation himself.

Within these cantos, Dante the poet aims to recreate the sights and sounds of this first terrace such that the reader may also participate in the purgation of pride in his own artwork, the poem. In order for the reader to receive spiritual edification through this chain of participation, Dante must represent, with an artistic skill nearly equal to God’s own, the images engraved upon the mountain side and ground. This precarious poetic task of representing with verisimilitude all that the pilgrim witnesses requires that the poet rise to an artistic height, a height from which many others have fallen on account of their presumption. Indeed, the poet must represent the handiwork of God as these divinely-designed images are the means through which the penitent are sanctified. And, miraculously, the poet’s precarious project does not falter. That Dante’s audacity does not lead to the same fate as Arachne, whose artistic presumption brought ruin upon her, suggests that Dante’s poetry soars by the permission of the divine will (12.43-45). Even more, this assurance of grace within Dante’s poem implies that the Commedia is, like God’s own art, a means of receiving spiritual transformation.

Through the poet’s depiction of the terrace of pride, Dante works to characterize the contemplation of art as a primary means of spiritual healing. Beginning with the artwork of God carved into the mountain, the poet creates a chain of participation in which the pilgrim, through seeing and speaking with the penitent souls participates in their sanctification as they perceive the images and speech imprinted within the divine sculptures. Dante then invites the reader to see and hear through his own God-graced artwork that they too may be saved from the folly of pride and conformed to the image of humility.

Alighieri, Dante. Purgatorio. Translated by Robert M. Durling. Vol. 2. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.