What is Fundamentalism?

Christian fundamentalists (think R.A. Torrey, A.C. Dixon, or recently, John Piper, Norman Geisler, Paul Washer, John MacArthur, Wayne Grudem, etc.) are part of the movement in Evangelicalism that originated in 1910s America. This phrase has been used to connote religious bigotry, abuse, and close-mindedness, but fundamentalists are merely Evangelicals with a complex (we will see whether this complex is merited further on).

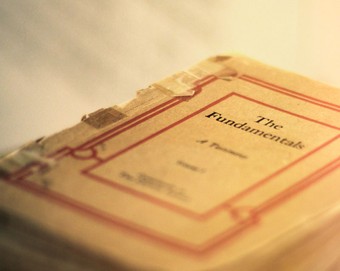

This was the branch of American Christianity that found its roots in the First and Second Great Awakenings; Pietism, Presbyterianism, and the vestiges of Puritanism also became early influences for Christian Fundamentalism. At its core, however, fundamentalism is reactionary against the liberal and modernist theologies of the 19th century, and herein lies the rub. Evangelicals, wary of this liberal theology, published The Fundamentals, a text out of Biola University. The voluminous text instructed its readers that its doctrines espoused were to be doctrines believed if one was to call themselves truly Christian. These revolved around the “Five Point Deliverance” of 1910s Presbyterianism. This consisted of the following: 1) the inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible, 2) the virgin birth of Christ, 3) the (penal-)substitutionary atonement of Christ, 4) the bodily resurrection of Christ, and 5) the historicity of the biblical miracles. These were a response to the modernist denials listed in Vol. 4 of The Fundamentals. R.A. Torrey writes, “Modern Spiritualism denies 1) The inspiration of the Bible. 2) The fall of man. 3) The Deity of the Lord Jesus. 4) The atoning value of His death. 5) The existence of a personal devil. 6) The existence of demons. 7) The existence of angels. 8) The existence of heaven. 9) The existence of hell.”

The Hermeneutical Ramifications of Fundamentalism

This seems fine until we consider hermeneutical freedom and the proper limits on that freedom. Of course, texts have meaning, but why is the biblical text different than other texts in how it should be interpreted? Sure its construction was divinely supervised, and authors are not solely behind the speech-acts of the text (God is, as well), but that should not change the fundamental way we, say, interpret Biblical miracles. It is one thing to say that Jesus turned water into wine, but wholly another to say that the mythical flood narrative, Job’s narrative, the Creation Myth, Jonah’s narrative, or the parting of the Red Sea, is to be taken literally/historically when they are clearly depicted as myth (genre-wise). A reader should be able to read the text as it presents itself–not as Fundamentalists present it.

Other than the historicity of the miraculous, we have another rub in the first point of the five aforementioned: “the inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible.” These doctrines, and inerrancy in particular, are defined in The Fundamentals. R.A. Torrey thankfully punts on the doctrine of inspiration. He writes something to the effect of “many good men have struggled to find a definition, and I will not attempt to find one here.” But a broad definition is assumed. This could be consolidated in this phrase, “the text has been divinely supervised and God was directly acting as an agent in the writing of the text.” I take no issue with this assumed definition. Also, whenever inspiration is mentioned, the caveat is also listed “if interpreted and understood properly” (a wonderful addition, I might add). But what of inerrancy?

Inerrancy is defined in The Fundamentals as the property of the text that ensures it is “without mistake or fault.” This is a function of inspiration for Torrey. The problem with this definition, though, is how it functions in the real world of public hermeneutics. I too affirm that the Biblical text is without mistake or fault, and I am not a strict evangelical. But this has an assumed hermeneutic behind it: a literal-historical hermeneutic, which might not be palatable for the reader for reasons already discussed.

The Fundamentalist Complex

The complex, at its core, is to be a reactionary against anything deemed as liberal or deviating from the Fundamentalist way. I know this from experience. I was privileged to attend a conference at The Master’s Seminary led by John MacArthur and Paul Washer among others. These were the Fundamentalist heavyweights. They were dressed in suits and, in both appearance and substance, from the 1910s themselves; they began to preach polemics and apologetics and I, as an outsider studying black liberation theology, was overrun. They began to say with a vigor that Catholics were not saved and the pope presented a threat to the fundamental interpretation of scripture (since he relies on tradition in his interpretation over reason and common sense alone).

I honestly could not take much more of it, so I went into the lobby and found a seminarian studying Greek. I approached them and inquired about this complex (without calling it a complex). They proceeded to accuse me of being a detractor and a liberal, when I was only asking questions, never assuming or making statements. They finally asked me why I believe what I believe. I took this as an invitation to an apologetics/polemics fight and I politely declined by stating that my theology was based on exegesis and not on experience alone. They were somewhat relieved. I offered a question that received a horrific answer: What is loving about this anti-Catholic polemic? Their response verbatim was, “this is how we are supposed to love those who disagree with us.” “What,” I thought, “is loving about beginning an argument with someone who disagrees with you?” Then it clicked. They really think that every Catholic’s salvation is on the line, and unless they believe in justification by faith alone, etc., they will not inherit the kingdom of God. This is a rational issue. So it needs a rational solution: polemics.

Finally, I understood. I thought that love would drive these interactions; but instead, it was a fear of someone else’s eternal destiny in hell. For the Fundamentalist, polemical evangelism is the primary way to properly love the other.

This horrified me but confirmed my suspicions.

The Resolution

This complex within Fundamentalism needs to die and soon. A proper reader of Jesus Christ would instantly realize that Jesus’ inclusion mimics God’s soteriological inclusion in His mission. God is a missional God who sends himself for our sake continually and eternally. Reflect on this: are you the stumbling block for unity? Do your ideas, agendas, philosophies, dogmas, etc. bring disunity? Drop them. Bring about unity in the spirit through love. Conformity is a cancer on Christian unity and it must be killed in its entirety.

This cancer on Fundamentalist Evangelicalism is undeniable but is not a reason for dismay. There is hope. Love always wins out because God is love. There is no hope for those who do not love. Woe to those who begin conversations polemically instead of making the first step in love and acceptance.

1 Comment

Leave your reply.