This week I asked my friend and officemate here at the University of Aberdeen if I could re-post a great blog he wrote about the ethics of Tom’s shoes and consumerism in a globalized world. Enjoy!

Driving through Aberdeen city centre this morning I noticed a woman walking to the office in a business suit. It isn’t my habit to check out office workers on their morning commute, but I was attracted by a distinctive white tag on the back of her shoes. Like many in the Christian world, Toms Shoes is now a brand that I recognise as easily as Coke, Apple or Disney. It’s pretty cool that such a socially-minded entrepreneurial endeavour as Toms is now making inroads into markets as obscure as oil and gas executives in northern Scotland.

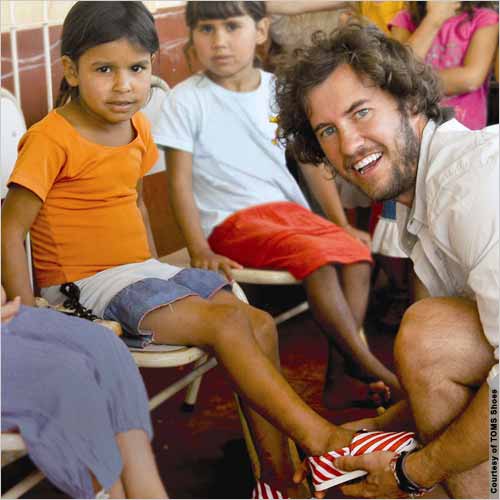

Toms, if you are unaware of it, is a shoe company established less than a decade ago by a young Texan businessman Blake Mycoskie. The pitch is simple and attractive. For every pair of shoes you buy from Toms, Toms donates a pair of shoes to impoverished children in Africa. The shoes have a simple elegance, a design that goes well with everything. The sales have grown year on year and now a company that started in 2006 in California, has scores of styles and designs on sale across the western world. While I have no interest in serving as the theological police, nevermind the fashion police (two roles I am certainly ill-equipped to perform), Toms raises some issues that thoughtful Christians ought to wrestle with. The first is the inherent problem with the Toms model. The second is the inherent problem with justice-orientated consumerism. And third, we might want to consider how Toms might expose our desires.

So what’s wrong with the Toms model? Well before Toms came along, it wasn’t the case that no shoes were being made, bought or sold in the townships of Angola or the slums of Argentina. So while we don’t want to deny the obvious worth of giving shoes to kids who otherwise wouldn’t have them (!), we must also recognise that such an activity distorts pre-existing markets. This is especially a problem if you are a Christian who thinks that capitalism is a good thing or that the integrity of markets should be respected. We buy a pair of Toms at the mall in Glasgow or Grand Rapids and think we are doing something good but we have to struggle with the economic reality that creates in the shoe stalls of a little city like Ganda in Angola. (Now I must add that Toms now makes some of its shoes in the places where it gives shoes away. This is a massive improvement on the initial model but nonetheless the inherent weakness in the model persists.)

Secondly, we should step back a little from Toms and consider the phenomenon of socially-minded consumerism in general. Toms is an excellent example because on the face of it, how can anyone raise any objections to it? But the problem of global inequality is intricately embroiled with the problem of Western consumerism. So Toms, or Blake Mycoskie’s new initiative Marketplace or even fairtrade and localvore food is an attempt to address problems of injustice, inequality or environmental degradation through the very phenomenon that (in part) created the problem in the first place. That infamous Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek explains the problems with trying to save the world through ethical shopping in this 10 minute video.

But with my final thought, I’d love to zoom out even further and consider what is motivating us when we are attracted to these kinds of initiatives. If you are anything like me, the choice in the supermarket to buy the eggs from happy free range chickens over sad cooped up chickens is one that returns a tiny, little swell of self righteousness. It is almost enough to justify the extra expense! In the same way, the lure of Toms shoes or its related products is the desire to make the world a better place in the midst of our everyday lives. This is a wonderful, positive impulse. But does it result in a wonderful, positive outcome? The problem with ethical consumerism is that it imagines the world is simple enough to be resolved with good intentions.

Toms wants to do good and in effect puts scores of little shoemakers around southern Africa out of business. Whether we turn our attention to coffee or mobile phones, jewelry or chocolate, there are many good initiatives that we should support but they all have significant consequences. These compromises remind us that the world we live in is thoroughly out of kilter. The Fall has left us problems that are seemingly intractable. Sometimes, we are attracted by initiatives like Toms because we want the world to be simpler than it is. Rather than making the world right, if we’re honest, we often find ourselves buying into these ideas because they make the world simple.

I’m not against trade and capitalism, social entrepreneurship and ethical consumerism. I don’t want to offer a teaching of despair where we raise so many problems that we have nowhere left to turn and actually act. Christians are called to join with God in making the world more just and perhaps experiments like Toms are important steps towards finding effective ways to achieve just that. Yet we should also be aware of how such models still let us down, how they open up into complicated contradictions and how very often, these measures don’t make the world more just, they just make us feel more right. And that can be a dangerous place to be.

Kevin Hargaden: @KevinHargaden; Hargaden.com/kevin

1 Comment

Leave your reply.