O come! O come! Emmanuel!

And ransom captive Israel;

That mourns in lonely exile here,

Until the Son of God appear.

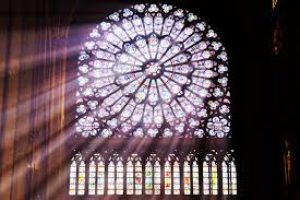

Advent is a time of mournful waiting. Participants in this season undergo a theatrical embodiment of the struggles of the people of God. In this drama, the Church relives, in a sense, a time in history in which the Messiah had not yet visited his people. We participate in such a drama in order to focus on the approach of Christmas appreciating the incarnation of God. The Church also reflects on the current status of the world, longing for the second coming of Christ.

Recently, Donald J. Trump announced that he was going to relocate the embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. This unprecedented action sparked protests world-wide and small skirmishes along the border of the Gaza Strip. Many American, Evangelical Christians celebrated this action, seeing it as some sort of fulfillment of prophecy and a step in the right direction for God’s plan. Other Christians in the rest of the world denounced Trump’s actions as it may cause more violence than to promote any lasting peace in the region.

This conflict is incredibly complex, and I have neither the credentials, experience, nor wisdom to speak to its solution. However, I see an alarming trend in Christian thought that I wish to address under the guise of an advent reflection. Brothers and Sisters, we cannot allow specific promises of land to ancient Israel to be our controlling hermeneutic in our Bible reading.

Moshe Greenberg, a prolific American-Jewish scholar, addressed this topic in an earlier event in the Israel-Palestine conflict. His chapter entitled, “On the Political Use of the Bible in Modern Israel: An Engaged Critique” counters the “Nationalist camp” with Jewish scripture and tradition.1 “They prize the biblical picture of Israel as a ‘muscular’ people, making war, conquering cities and countries, and establishing an empire. For them, Scripture conveys the fresh air of independence and sovereignty” (Greenberg, 464). He goes on to suggest that Scripture and Tradition itself presents the reader with an “internal standard” by which to judge this position. He argues that God’s instruction is repeatedly summarized and distilled into something akin to “Love your neighbor as yourself.” He writes,

“Thus the Torah (In the Decalogue), the Prophets (Isaiah, Micah, Amos, and Ezekiel), and the Psalms all agree that the essence of God’s requirement of man does not include the national task of settlement of the land or comprise chiefly proper worship or matters of purity and impurity, but consist mainly (quite in the spirit of prophecy) of the establishment of a just and mutually loving society” (467-468).

Greenberg presents a controlling hermeneutic or a lens through which one ought to read scripture. “Love your neighbor as yourself” must color our interpretations of the text and how we apply them to our modern politics.

This “internal standard” is taken up and advanced by Jesus and his disciples. The New Testament explains that loving action must extend to one’s neighbor, one’s enemy, and even a tyrannical government. Far from an ethic that passively allows others to take advantage of oneself, Jesus proposes and embodies an ethic that actively sacrifices oneself for the enemy. For the Church, “Love your neighbor as yourself” is taken to mean answering Jesus call to “pick up your cross and follow me.”

As I write this reflection, the world is far from the renewal promised by Jesus Christ. My home-state is on fire, Political unrest in a number of African countries, Slavery in Libya, massacres in South-east Asia, Racism in Europe, Gun-violence rampaging in America, etc., and now a kindling has been lit in the powder-keg that is Israel-Palestine. Advent is a time for mournful hope – a mourning that acknowledges that this world is far to broken for us to fix and a hope that confesses that Jesus Christ will return to make all things new. What Christians lose by focusing on the Land of Israel is the very thing that that Land has always pointed to: the cosmos. From the beginning, the promise God made to Abraham had global and cosmological ramifications: “All the nations will be blessed through you.” This promise is fulfilled not in some modern-day nation-state, but through the death and resurrection of Jesus and in his return to redeem all things. Why settle for a small piece of land when Jesus promises to redeem and bring everlasting peace to the whole world? Whether or not Jerusalem is recognized by the USA as the capital of modern-day Israel holds no real eschatological implications. On the other hand, to “love your neighbor as yourself” radically impacts our participation in the Father’s redemptive mission.

There are many sides to this conflict and many ways our world can move forward. For Christians, our response to this situation, and every situation we may find ourselves in must be controlled and informed by the radical enemy-love of Jesus Christ displayed on the cross. For Advent, we may reflect on the situation of our broken world, and with mournful hope, eagerly await for the return of Christ. We may cry out in mournful and expectant prayer with the Church in both Israel and Palestine, “O come! O come! Emmanuel!” In Advent, we relive the anxiety of a Messiah-less world in order to rejoice that indeed, Jesus is the “God is with us” and he is coming again. He will bring true and lasting peace that we have been longing for. Until then, we have been given the Holy Spirit so that we may fulfill the law of Christ here and now.

- Greenberg, Moshe. “On the Political Use of the Bible in Modern Israel: An Engaged Critique.” In Pomegranates and Golden Bells: Studies in Biblical, Jewish, and Near Eastern Ritual, Law, and Literature in Honor of Jacob Milgrom, edited by David P. Wright, David Noel Freedman, and Avi Hurvitz, 461-71. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 1995.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.