Maybe you’ve never heard of mewithoutYou. That saddens me. This post-hardcore melodic folk band from Philadelphia is certainly one of my favorites. Their 5th studio album, Ten Stories, was just released on May 15, 2012. This is their first album released after their record-label contract with the Christian record company, Tooth & Nail, expired.

What sets mewithoutYou apart from other Indie Rock bands is the beautiful oddity of their frontman. Perhaps there has never been a lyricist as honest, profound, and prophetic as Aaron Weiss. All of his lyrics are full of philosophical subtlety and self-reflection, though it is often expressed rather eccentricly. One intriguing aspect of the band for me is the steady progression away from exclusivism towards inclusivism, but this progression has been subtle (I have much more to say on this issue as it relates to the intersection of Christianity and music — especially regarding the whole notion of “Christian Music, ” which I take to be a misnomer — but will refrain until Mumford & Sons comes out with their new album). It seemed like such a progression away from explicit Christian ideology would continue into their fifth album, especially since they were finally free from their Christian label (and the associated stigma). I also felt this progression would continue after meeting Aaron Weiss last May when I had the wonderful privilege of seeing mewithoutYou perform live. The band is very accessible to its fans — often welcoming anyone to potlucks prior to their shows — so I thought I could possibly sneak a chat with Weiss after their performance. Thankfully I was able to talk with him for a bit and listen in on his conversations with other fans. Of course, being a good freegan, he offered all of us some of his food which he had behind the stage. The most striking thing about meeting Weiss though was watching his reluctance to express his faith in God directly. This is in stark contrast to interviews he conducted in the early years of the band’s history where he was remarkably outspoken. Weiss’ answer to one fan in particular, who appeared to be a non-Christian, was a bit disconcerting. When asked about his belief in God, Weiss essentially articulated that it is impossible to be certain of anything and to claim otherwise is arrogant and pretentious. Now, I’m actually pretty sympathetic with this sentiment. Certainty is a tricky subject, but Christianity is not about certainty, it’s about faith. Additionally, this is why revelation is so crucial theologically. We are inside a box, as it were, and we need someone outside the box to make sense of everything for us. God must reveal himself if we are ever to know him. There is a humility to this that erases the arrogance and presumption that Weiss — and I! — fear. I bring all of this up because when I purchased mewithoutYou‘s new album I came to the new tracks with this interaction at the forefront of my mind.

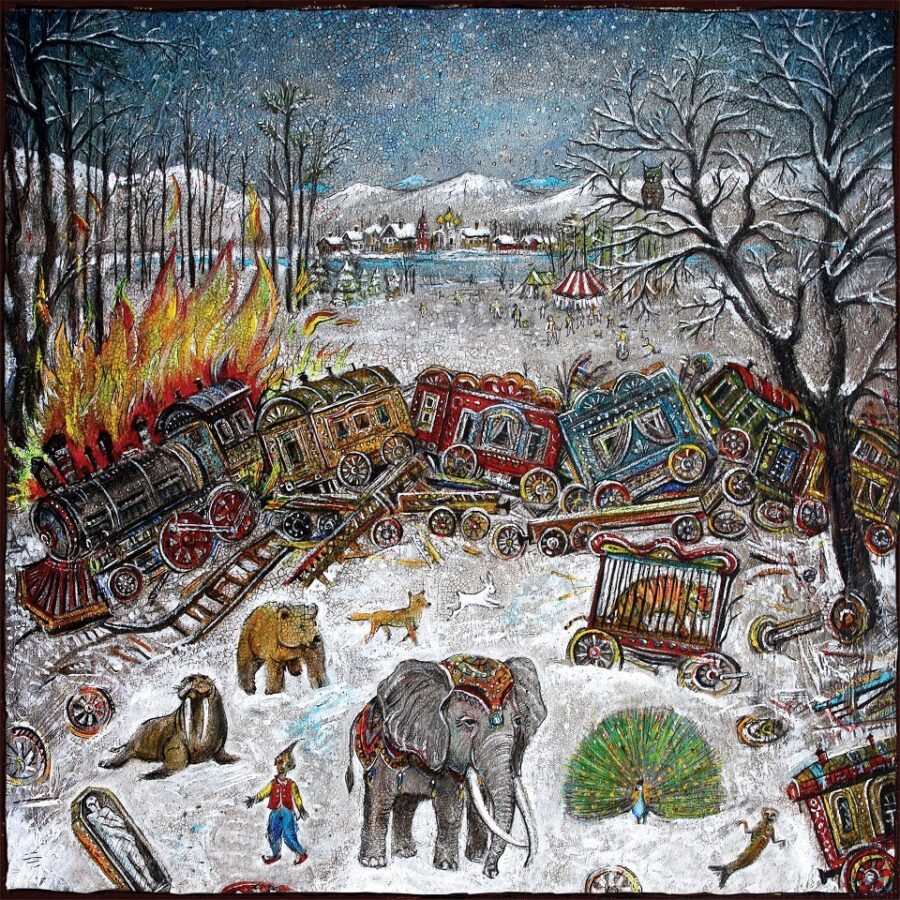

The new album, Ten Stories, follows from the previous offering, It’s All Crazy, It’s All False, It’s All A Dream, It’s Alright, with a similar focus on the perspective of animals. Although, the album feels much more like a raw version of their third album, Brother, Sister (and as my conclusion bears out, there is an interesting overlap in content, though with different outcomes). This time the focus on animals relates to a coherent story—a true story about a Circus-Train that crashed in Montana in the late nineteenth century. Ten Stories utilizes the Circus animals to explore similar topics often explored in previous albums, most notably — and relevant to my interaction with Weiss — the certainty of reality. Rather than offer a true review of the album, I would like to look at the tension expressed regarding reality in Ten Stories.

Certainty and Reality in Ten Stories

In the opening track, “February 1878,” we are introduced to the Circus-Train narrative. A crash was caused by the Elephant who wanted to free the caged animals. After the animals begin to flee, they in turn summon the Elephant to come, who then proclaims,

My tusks are dull, my eyes half-blind, too old to run, too big to hide, and have neither friend nor enemy, nor that phantom ‘self-identity,’ nor concern for what they’ll do to me, now my children run free.

At the outset of the album we have the main protagonist, the Elephant, show a socratic sense of purpose and resolve (regardless of the consequences). In this statement, the Elephant also makes it clear that she lacks ‘self-identity,’ which is an important theme for the album. The chorus of the album’s catchiest song, “Cardiff Giant,” repeats the refrain, “I often wonder if I’ve already died,” and the bridge of the same song follows, “Or if the ‘I’ is an unintelligible lie.”

The following Track, “Elephant in the Dock,” imagines a fictive court-room scene in which the Elephant is condemned to death with the refrain: “Hang! (The Elephant Must Hang!).” Prior to the sentencing, the Elephant refuses to swear the oath, stating, “I don’t know anything about truth, but I know falsehood when I see it, and it looks like this whole world you’ve made.” Again, we see the emphasis on questioning the true nature of reality. The Elephant then prays, “Lord, for sixty-so years I surrendered my love to emblems of kindness, and not the kindness they were emblems of.” The prayer of the Elephant shows that there is a reality (“kindness”), but that reality is vaguely hinted at in the many shadows or “emblems” of this world. Though the confusion about the nature of reality is further expressed when the Elephant addresses the Children with a solipsistic quandary: “Children, sometimes I think that our thoughts are just things, and sometimes think things are just thoughts.” Then in a brilliantly poetic verse the Elephant reflects on his imminent death:

My trial can no more determine my lot, than can driftwood determine the ocean’s waves. Brandish your ropes and your boards, and your basket-hilt swords, but what is there can punish like a conscience ignored? Yes, my body did just as you implied, while some ghost we’ll call ‘I’ idly watched through its eyes.

In a quasi-Gnostic and Platonic sort of way, the Elephant draws a distinction between her body and her soul or ego, and yet there is still some reluctance in affirming that this ‘I’ truly exists. Similarly, in “Aubergine,” which is apparently a love song about two dogs, Aubergine says, “You can be your body, but please don’t mind if I don’t fancy myself mine.” A statement is also made about heading down a “solipsistic road” and then getting off to “ask for directions.”

The track, “Fox’s Dream of the Log Flume,” records a tragic love story between two foxes. It opens with: “Provisionally I, practically alive, mistook sign for signified.” This track is perhaps the most revealing of Weiss’ personal tension regarding the nature of reality. He reflects on the fact that “some with certainty insist that no certainty exists” and later in the song expresses the tension this way, “our aimless arrow words don’t mean a thing to whether I think it’s pretty obvious that there’s no God, and there’s definitely a God!”

In “Nine Stories” the jubilation of freedom is expressed. The Circus animals are free and this great freedom is praised by an Owl. Yet intriguingly, as the Owl sings about this new found freedom, recording all the wonders that she has seen, she tells a Walrus that “Jacob knows a ladder you can climb,” implying that there is a way up to see the same great heights as the Owl. Of course, the imagery is directly from the famous Genesis story about Jacob’s vision of a heavenly ladder mediating between heaven and earth. Sadly, the song ends with the Owl singing about an unforeseen corollary to Jacob’s ladder, “if the pleasures of your heaven ever ends, that very ladder just as well descends.” Are we to assume that Weiss is here expressing his struggles with the idea that Heaven might not be all its cracked up to be?

The album ends with “All Circles,” which lyrically consists of one major line sung in a loop: “All circles presuppose they’ll end where they begin, but only in their leaving can they ever come back ’round.” This track is the 11th song on Ten Stories. As the eleventh track, it offers no reflections on any of the animals that survived the Circus-Train crash (the ten stories relate to the first ten songs). As a conclusion to the album, I interpret the final track to mean that the stories of the personified animals are parables — prophetic harbingers — that reflect our experience of reality in the present. Ten Stories explores a story of caged animals who experience the joy of freedom, only to find heartache and to be confronted with the strangeness of the “real world.” And at the album’s end the quest for the meaning of reality and existence leaves the listener going in circles.

Conclusion

Fans familiar with mewithoutYou will recognize the pervasiveness of the motif of reality in their previous albums generally and Brother, Sister in particular. Brother, Sister begins with the opening words of the first track, “I do not exist, I faithfully insist,” and concludes 12 tracks later with the words, “I do not exist, only You exist.” As the album progresses three tracks are interspersed in sequential progression — “Yellow Spider,” “Orange Spider,” and “Brownish Spider” — which symbolize a developing decay that occurs throughout the course of the album. The progression of the album climaxes with the affirmation, “only You exist.” Whereas humanity is contingent and fragile, being subject to decay, God exists and he exists necessarily, because his reality is the only true reality: a theo-solipsism. This is why I regard the album Brother, Sister to be absolutely profound (and one of the best albums of the last decade). The fact that Ten Stories wrestles with this theme as well is something I completely welcome and enjoy. Though it is sad that whereas Brother, Sister concludes with “only You exist,” Ten Stories never takes us past the uncertainty of our contingent reality to the constant One who never changes.

13 Comments

Leave your reply.