There is a town in Northern Uganda named Gulu. To get there from Kampala—Uganda’s capital—our bus traveled about 200 km, cutting through lush tropical jungles and eventually emerging into the dryer terrain surrounding Gulu. After nearly two weeks in Kampala, I thought I knew a lot about Uganda (a very arrogant assumption to begin with), but just a few minutes in Gulu proved me wrong. The city, its people, and its struggles were different.

The worship pastor at my church is a Ugandan who came to America many years ago and now leads regular mission trips back. Before I went there with him, he encouraged me to read as much as I could about Uganda so that I was as prepared as possible. And there was a lot to read.

Uganda is a former British colony that gained Independence in October of 1962. Between then and now, it has seen a handful of leaders including the infamous Idi Amin. Uganda is a contradiction. It is full of life and promise, but at the same time it is fighting the battle that so many former British colonies fight: establishing a stable and honest government.

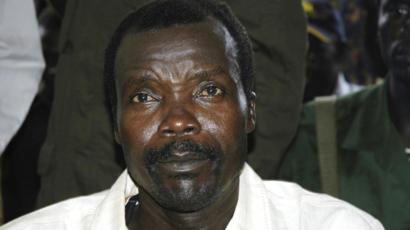

Just from that starting point, Uganda’s people have a lot on their hands. Then enter Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army. If you haven’t already watched the highly proliferated Kony 2012 video and don’t have any previous knowledge of Kony, here is the short summary: Kony is a vicious thug that parades around Eastern and Central Africa, kidnapping young boys and turning them into killers. In addition, he and his followers kill the boys’ parents, rape their sisters and brutally disfigure whomever they please. It is estimated he has kidnapped nearly 66,000 youths. This has not gone completely unnoticed—especially recently— with the particularly successful web campaign launched by Invisible Children (IC) to make Kony famous. If you haven’t already seen the video, I suggest a view.

Whereas millions of people are re-posting, re–tweeting, and sharing this powerful video, there is also a counter movement saying it’s a misleading and overly simplistic plan. The most notable bastion of this is a blog titled “Visible Children.”

Is this cause worthy of support, or another poorly thought out scheme at improving the world that ends up being more promotion than solution? I want to think critically about whether or not I should personally partner with this campaign as a Christian.

I watched the video. I read articles. I even spent a limited amount of time in the region. But I am still not entirely sure where I stand. Though, as you will see, I lean in one direction over the other.

The first issue that springs to mind is if there is a connection between the IC and violence in the region. You don’t have to read very widely to see vitriolic critiques that call religion the greatest propagator of war. This isn’t entirely fair, but there is some truth to it. Good intentions can have heartbreaking results. Jewish Zealots, Islamic Extremist, and Christian Crusaders all contribute to the stereotype connecting religion and violence. There are two ways that I can see the IC campaign potentially spurring violent activity:

First, IC has advocated sending U.S. troops to interact with Ugandan troops. So, whereas the campaign is interested in bringing Kony to an international court to be tried, violence must somewhere take place in order to make that happen. Furthermore, the victims of this violence may end up being some of the same boys that IC’s is trying to protect.

Secondly, there is an imperialist flavor to any instance where the West comes in to help the East. I am sure that there are Ugandans who feel that Kony is a Ugandan problem that can be solved with Ugandan ingenuity and resources. Of course, the whole country probably isn’t of one mind here, and Kony has definitely operated in more than just Uganda. In fact, Northern Uganda has not seen Kony for a handful of years now – another reason that Ugandans may not want to have any further involvement.

On the other hand, there is something that strikes a sensitive chord in this campaign.

Kony is the worst kind of monster because he intentionally proliferates his evil acts, making zombies out of young boys and leaving emotional and literal scars on the communities that he invades. Not many would be opposed to capturing a murderer or rapist roaming their neighborhood’s streets even if it meant some violent measures had to be taken. It would make sense to view this situation as analogous, but on a larger scale. Kony is a criminal, intentionally putting the lives of innocent people in danger. It is likely that there will be violence in the process of arresting Kony, but how much future violence will be avoided in the act?

Another aspect of this campaign that I find particularly attractive is how quickly it can involve its viewers. The video does an excellent job of presenting the problem and then providing simple ways that those who are interested can take action. Not many videos can do that. The Visible Children blog critiques the video this way: “these problems are highly complex, not one-dimensional and, frankly, aren’t of the nature that can be solved by postering, film-making and changing your Facebook profile picture, as hard as that is to swallow.” This is a clever line, but it is a gross misunderstanding of the power of visibility. The number of people aware of your cause, whether it is a theology blog or a humanitarian project, dictates what you will be able to accomplish. Visibility is currency. That’s part of why Google’s founders are filthy rich. Each click of a thumbs up button on Facebook may not make Kony glow ever brighter to infrared sensors (if only), but it motivates people with considerable power and resources to act.

Ultimately, I think there are too many good ideas here to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

One last point, and it’s going to be an inflammatory statement. So, if you’re already annoyed with me, please keep reading so that I can finish the job. I see a lot of people posting criticisms of the Kony 2012 campaign. I have talked to them and many don’t actually agree with the criticisms they post, they just want people to “be informed.” I actually had a similar response a few minutes after watching the video. And I think my mind went through this process: Millions of people have watched this video. It’s now about as mainstream as McDonalds. I don’t want to be McDonalds. I’d better come up with something different to post..” I became an Internet hipster. I was guilty of wanting to be counterculture simply for its own sake.

If you actually disagree, and genuinely think that the Kony 2012 campaign is a bad thing—fine. That’s your prerogative, and I would never accuse you of thoughtlessly being anti-mainstream. In fact, this very post mentioned some of the negatives. But if you’re like me, and you wanted to be critical because you thought it might give you a social or intellectual edge – please rethink your motives because they are probably self-centered.

9 Comments

Leave your reply.