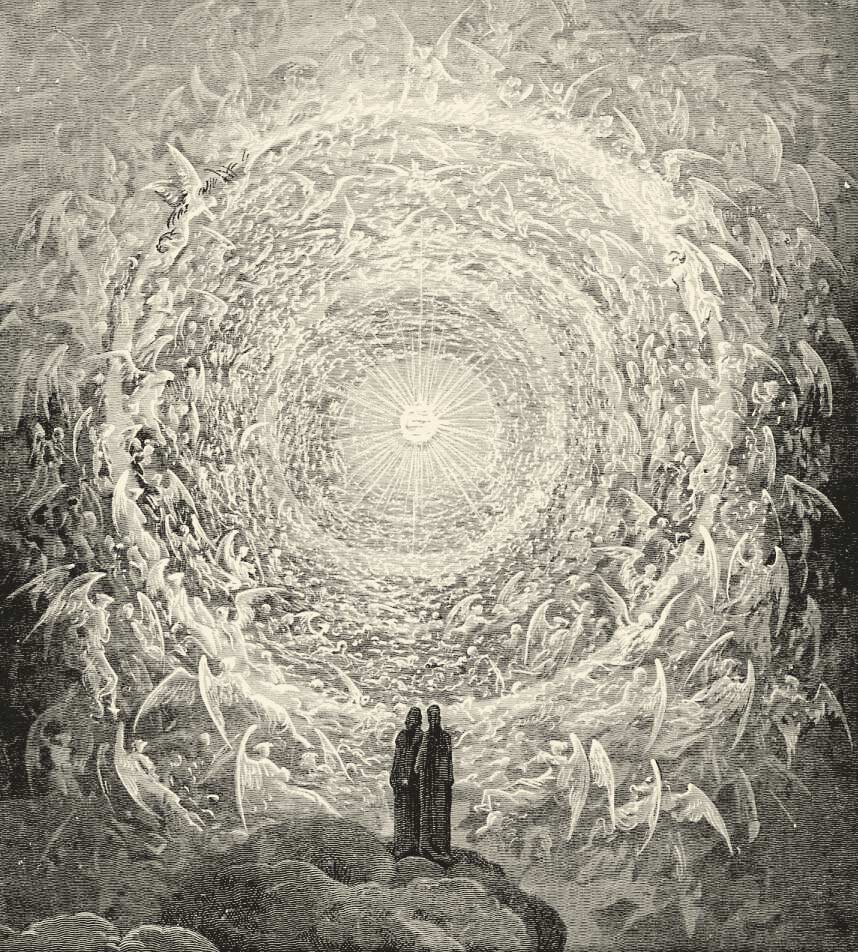

Our imaginings of the afterlife often include getting answers to questions the knowledge and experience of the world couldn’t answer. Likewise, the pilgrim of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy seeks out heavenly wisdom to satisfy his own burning question: How is God just if people who never received knowledge of Christ’s salvation or the opportunity for baptism are condemned? In Canto 20, the souls represented in the heavenly sphere of Jupiter direct the pilgrim’s attention to the souls of the “the highest in degree” (Par. 20.36). To the pilgrim’s astonishment, Trajan and Rhipeus– historically known pagans– shine among them. While the legend of Trajan’s miraculous salvation by the intercession of Pope Gregory was known to Dante through church tradition (and illustrated in the carvings along the terrace of pride in Purgatory), the appearance of Rhipeus, a character of little significance briefly mentioned in Virgil’s Aeneid, comes as quite a surprise– “What things are these?” (20.82). The mysterious inclusion of Rhipeus among the blessed provokes the reader to once again consider the contrasting tragedy of Virgil (the pilgrim’s guide through the Inferno and Purgatorio) who “did not sin,” yet remains exiled from the heavenly court on account of his ignorance having died only a few years before the revelation of Christ (Inf. 4.34). How does heaven explain the presence of this pre-Christian pagan among them at the exclusion of another? Though the souls of Jupiter participate in everlasting communion with God, their vision cannot penetrate the uttermost depths of the divine mind and therefore cannot provide an account of the divine reasoning. Yet they do not leave the pilgrim’s hunger for knowledge unfed. They praise the incomprehensible depths of God’s Providence which, though ultimately impenetrable to mortal vision, offers a space for human hope. The poet then practices this “lively hope” by transforming Virgil’s ambiguous, but inescapably narrow, vision of Rhipeus’ fate in the Aeneid into a spacious and welcoming opportunity for exercising hope in the providential work of God in the Comedy.

Though the character of Rhipeus appears as a mere bit player in Virgil’s Aeneid, the poet assigns a uniquely significant epithet to the Trojan prince. The first named among Aeneas’ comrades who fight alongside the hero in the final battle for Ilium, Rhipeus soon perishes in a skirmish. Virgil records, “Rhipeus falls too, the most righteous man in Troy, the most devoted to justice, true, but the gods had other plans” (AN 2.532-534). The disproportion between Rhipeus’ brief role and the poet’s praise is striking, if not suggestive. After noting the surpassing righteousness of Rhipeus, Virgil adds the ambiguous clause, “true, but the gods had other plans.” It seems that, in spite of Rhipeus’ verifiably supreme commitment to justice, the gods deemed an outcome– in this case, death– different than one which perhaps Rhipeus merited since the Trojan’s righteousness seems to stand in contrast to the divine “plans.” Though it is difficult to determine the precise implication of Virgil’s reference to the gods’ judgment, the poet’s meaning is so purposefully obscured that it almost seems as though he wishes the reader to suspect him of some impious skepticism. If the reader understands the gods’ “plans” to refer to Rhipeus’ death, then perhaps Virgil is ironically suggesting that the fate assigned to Rhipeus by the gods was unjust with regard to the Trojan’s own justice. Rather than receiving a more favorable fate from the gods, Rhipeus– by Virgil’s account– is a tragic victim of an untimely death from which no amount of righteousness could deliver him. The Aeneid’s representation of Rhipeus’ fate, though open-ended, doesn’t offer much room to exercise the possibilities of hope and instead casts a narrow and skeptical vision of divine judgment.

In Paradiso 20, Dante transforms Rhipeus from a Virgilian victim of fate to a recipient of heavenly grace. The company of souls explains to the pilgrim:

“The other, because of grace that flows from so

deep a fountain that never creature’s eye pierced

to its first welling,

devoted all his love down there to righteousness,

wherefore, from grace to grace; God

opened his eyes to our future redemption,

and he believed in it, and suffered no longer

the stench of paganism, but reproached those

perverted peoples for it.

Those three ladies were his baptism whom you

saw by the right wheel, more than a thousand

years before baptizing began.” (Par. 20.118-129)

Repeated three times over the course of the passage, the word “gazia” or “grace” carries the salvation narrative of Rhipeus. God’s first grace grants the Trojan the unwavering devotion to justice. The divine generosity bestows a second grace when Rhipeus receives a vision of future salvation. This pattern of ever-increasing grace culminates in Rhipeus’ spiritual baptism enacted by God through faith, hope, and love centuries before baptism began. Whereas the “other plans” of the Virgilian deities cast a tragic shadow over the fate of Rhipeus, Dante reimagines these “other plans” to refer to plans of heavenly grace. In fact, Dante goes as far as to load the life and death of Rhipeus with divine grace such that the pre-Christian pagan receives a miraculously wrought salvation previously unimagined. The poet grounds Rhipeus’ graced life and heavenly blessedness in the mystery of divine providence.

God’s will, otherwise called providence or predestination, serves as the foundation for understanding divine justice and grace. After the pilgrim poses his question to the souls of heaven, they cry out together,

“Oh earth-bound animals! oh gross minds! The

first Will, good in an of itself, the highest Good,

Has never changed.

That is just which is consonant with it; no

created goods draw it, but it by radiating causes

them.” (19.85-90)

God’s justice comes forth in full harmony with the perfect, unchangeable, and altogether inscrutable divine will. Though the will of God lies beyond the grasp of human understanding and, as the supreme cause of all that exists, cannot be altered by human power, providence does not suppress hope in a plurality of potentialities. Rather, the hiddenness of providence paired with the supreme power of God as the One who wills encourages the believer to pray in hope of a possibility. For by “burning love and lively hope” the prayer of a righteous man may

“overcome God’s will:

not as one man defeats another, but they

conquer it because it wishes to be conquered

and, conquered, conquers with its good will.” (20.96-99)

Since the will of God is both supreme and unchangeable, human prayer cannot actually conquer the divine plan. However, should God’s providence will to submit to another’s will and still carry forth “the highest Good,” then providence remains supreme, unchangeable, and also full of possibilities from the human perspective (19.86).

Therefore, through the reinterpretation of Virgil, Dante not only fills the ambiguous “other plans” with a Christian narrative, but also places Rhipeus’ story in the hands of Christian providence as opposed to pagan fate to create an altogether different response. Whereas the narrow and inescapable conclusion of Rhipeus produces Virgilian skepticism, the spacious and hidden providence of God bears forth Dantean hope. Through the reinterpretation of Virgil’s Rhipeus, Dante not only creates an opportunity for hope, but actively practices this “lively hope” in the invention of Rhipeus’ salvation narrative. In this way, the poet responds to the pilgrim’s doubt by example.

Though the pilgrim’s question, whether the judgment of the virtuous pagan who has never received the teachings of Christianity is just, cannot fully be answered by human knowledge, the blessed offer a theological lesson which the poet carries into action. They first declare the incomprehensible and perfect justice of God’s providence in which the discernment of God is hidden from mortal view. After the pilgrim notes this limitation, they recall the warning words of Christ recorded in Matthew modifying them slightly:

“…many cry ‘Christ, Christ!’ who at the

judgment will be much less prope to him, than

someone who does not know Christ.” (19.106-108)

Mortals judge by what is visible, but God judges the inward condition of the heart. As some who possessed true knowledge of God, but did not love Him will be banished from heaven, others who lacked full knowledge, but honored God may receive a seat among the blessed. Simply, the only thing the believer can expect in Paradise is a good surprise. While the pilgrim does not receive any definitive answer as to the outcome of the virtuous pagan, providence does provide space for active hope. The poet exercises this “lively hope” in the providence of God and in this hope reimagines Rhipeus’ story. The pilgrim cannot overcome the will of God, let alone understand the divine discernment, but the pilgrim– and the reader– are taught to hope by the poet’s demonstration.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.