It’s no secret that some of the best books are children’s books.

A few weeks ago, I was asked: “If someone were to really get to know you, what three books (besides the Bible) would they really need to read?” (Great conversation question, right?) My husband and I tried to answer for each other to see how close we came to guessing what the other had in mind. Richard’s guessed Dante’s The Divine Comedy, T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets, and Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. Definitely some of my favorites, but not precisely the ones that came to mind. While the these readings have certainly played a significant in my intellectual journey and theological formation over the last six years or so, the books that came to mind were actually books I had read between the ages of eight and thirteen. Wind and the Willows. The Silver Chair. The Hobbit. Harry Potter.

The best of children’s books have a way of sneaking seeds of hope into our hearts and saturating the soul with a longing that leans toward faith. At the same time, however, these books recognize our wounds: open, hidden, or scarred. The best of children’s books are able to both name these wounds and offer a salve.

Last week, as the ‘cyclone bomb’ storm raged over New England, I read Patricia MacLachlan’s The Poet’s Dog. My mother had given it to me assuring me it is one of those ‘really good ones.’ And it is. The Poet’s Dog is a story about two children, Nickel and Flora, who meet a dog named Teddy who is able to speak but only be understood by those who have ears to hear— namely, children and poets. The children, having gone looking for shelter from a winter storm after their family car breaks down and their mother leaves to find help, meet Teddy in a frosty wood where the poet named Sylvan used to live in a small cabin. Teddy leads them to the poet’s old home where the three of them hole up together until the storm is over.

While the three keep warm together over the days of wind and snow, the children learn about Teddy’s past: how he was rescued by Sylvan and taught to speak, how Sylvan had cared for him, how Sylvan became sick and had left one day to go to the doctor and didn’t return. The story of love and loss echoes forth into the story of the children who have temporarily lost the protection and care of their parents.

“It’s almost as if Sylvan saved you and brought you here so you could save us.” Nickel says one evening. Perhaps so.

After the storm settles and the children are reunited with their family, Nickel and Flora save Teddy from his grief by bringing him out of his lonesome woods and into their home. The Poet’s Dog is a story about love, a love which saves one from a storm and brings them into sanctuary.

At the end of the book, my mother left a small note:

Who rescued who?

Maybe we rescued each other.

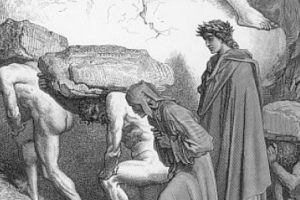

This was one of those moments when the simplicity of the children’s story struck upon a truth of deep and radiant beauty. A truth which gripped poets like Dante and Charles Williams. A truth which is, at its root, essential to Christianity. In the words of St. Anthony, it is this: “Your life and your death are with you neighbor.” In MacLachlan’s story, this is illustrated first through the relationship of Sylvan and Teddy and, in turn, Teddy and the children. This idea, that we cannot rescue ourselves, dwells at the heart of Dante’s Commedia and Charles Williams’ poetry, fiction, and theological reflections. However, for Dante and Williams, this interdependence between neighbors is the defining characteristic of the Church. As Williams’ points out, Dante’s pilgrim not only cannot save himself, but requires a whole company of saints to restore him from the dark wood. Without the intercession of the Holy Virgin, St. Lucia, and Dante’s own beloved Beatrice, the pilgrim could not have escaped the threat of Hell and recover the true path. Perhaps it is the same in our own lives. Williams asserts it is so. Whether in the common matters of life or the Church, Williams claims that “no man lives to himself or indeed from himself” (Williams,“The Redeemed City,” 104). Rather, we live by and from one another.

The Poet’s Dog illustrates this very reality and encourages us as readers to live with love that brings life to others. Through this love by which we both rescue and are rescued we experience the presence of HE who loved first.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.