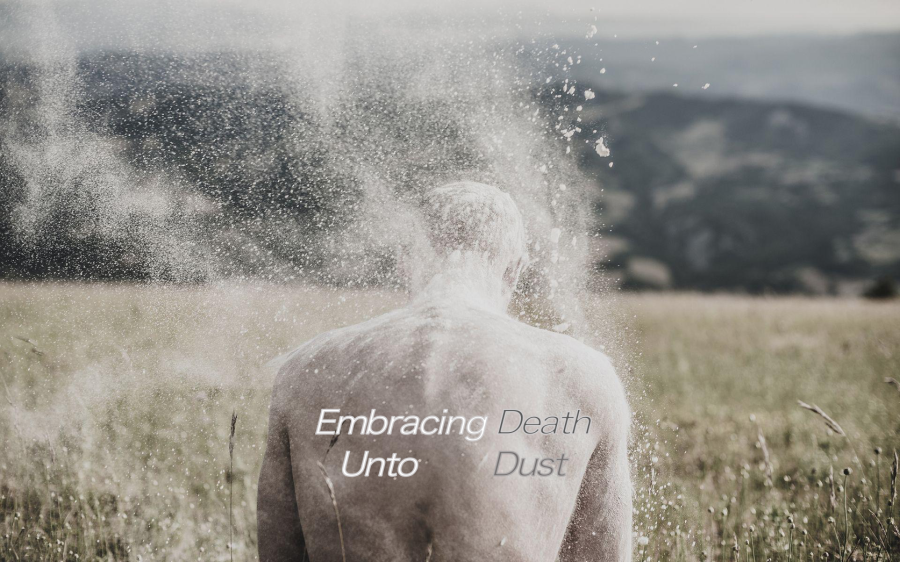

“By the sweat of your face you will eat bread, until you return to the ground, for out of it you were taken.

For you are dust. And to dust you will return” (Genesis 3.19).

Ever since then, humanity has been faced with a choice regarding this decree: either ignore it, avoid it, and live as if death were just an old wives’ tale, or understand it, accept it, and embrace it as a fundamental aspect of human existence. As of late in human history, society has become more and more terrified of the notion of death. Certain results of this fear, such as a sexually-crazed culture or the fact that churches never put cemeteries near their buildings anymore, crop up more and more. Stanley Hauerwas in fact connects the recent fear of death to certain medical and scientific trends. His comments are sobering, convicting, but inspiring.

Consider the implications of [Luigi] Giussani’s almost throwaway observation – “Luckily, time makes us grow old.” – for how medicine, and the sciences that serve medicine, should be understood. I think there is no denying that the current enthusiasm for “genomics” (that allegedly will make it possible to “treat” us before we become sick) draws on an extraordinary fear of suffering and death incompatible with Giussani’s observation that luckily time makes us grow old.

Our culture seems increasingly moving to the view that aging itself is an illness, and if it is possible, we ought to create and fund research that promises us that we may be able to get out of life alive. I find it hard to believe that such a science could be supported by a people who begin Lent by being told that we are dust and it is to dust we will return. For Christians to create an alternative culture and alternative structures to the knowledge produced and taught in universities that are shaped by the fear of death, I think, is a challenge we cannot avoid.1

It was Jesus who set forth the notion that true life actually comes through embracing one’s own death, walking straight into it, in order to come up on the other side free from the power of death altogether: “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. Whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 16.25). Similarly, one of his apostles: “Through the law I died to the law, in order that I might live to God – I have been co-crucified with the Messiah” (Galatians 2.19).

To be Christians, to be messiah-people – that means to be crucified people, to be those whose present existence demonstrates that death has no power, and therefore to be those who can walk in resurrection life in the present. Those who belong to Christ Jesus can be a living testimony to the defeat of death itself, and thus can bring hope to a humanity that is crippling in its fear of death. The ironic, unpalatable message is this: willingly die alongside Jesus, and death will have no power over you.

As Hauerwas so eloquently put it, Christians cannot avoid but create an alternative culture and modes of thought to those produced in institutions where death reigns through fear of death. For Christians, it should begin by constructing, both theologically and structurally, a cruciform worldview and life. To put it more practically in terms of normal church decisions: does, for example, paying pastors multiple hundreds of thousands of dollars create, encourage, and proclaim the death-embracing life that Hauweras, and, more importantly, Jesus, calls us to construct? How much has a death-fearing society slowly crept into to circles in which it should not be present? It will require a great work of grace to resist it, as well as a fresh breath of creativity to construct countermanding structures and practices. The good news is that our Lord is as strong as he is faithful.

It will be my prayer this Lent that those who are in Christ would learn to ‘die every day’ (1 Cor 15.31).

1 Stanley Hauerwas, “How Risky is The Risk of Education? Random Reflections from the American Context,” in Hauerwas, The State of the University: Academic Knowledges and the Knowledge of God (Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2007), 53.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.