Editors note: This is part two in a two part series looking back at the end of Major League Baseball’s so-called Steroids Era. For part one click here.

For a baseball fan growing up in Northern California, the late-90s and early 2000s were a great time. After some lean years through the mid-90s, the Oakland A’s began to turn things around. Carried by three great starting pitchers, 2 MVPs, and the exploitation of some market inefficiencies, the A’s success eventually became the subject of a best-selling book and an Academy Award nominated movie. Their cross-town rivals were no slouches either. The San Francisco Giants got a beautiful new waterfront stadium and had one of the greatest players of all time to christen it. Barry Bonds won four straight MVPs from 2001 to 2004 and the Giants won the National League pennant in 2002.

But around the same time the Steroids Era was ending, so was the success of both franchises. As the public began to understand the extent of MLB’s performance enhancing drug problem, the accomplishments of many baseball stars began to tarnish. Few regions were hit as hard as Northern California. Both of the A’s MVPs during this era–Jason Giambi and Miguel Tejada– later had their names associated with steroid use. The most recognizable star in the game (Bonds) became the face of the Era. The source of of his PEDs, the Bay Area Laboratories Co-Operative, inextricably linked the region to steroids. Did that detract from the success of these two franchises? Did it diminish the enjoyment of that success looking back on those years? To me, not at all. The way in which the Steroids Era came to an end, the effect on baseball’s history that came in the aftermath, and society’s collective reaction all provide interesting points for discussion.

As I noted in yesterday’s post, the unofficial beginning of the end of the Steroids Era occurred when Senators John McCain and Byron Dorgan told the MLB commissioner and MLBPA executive directors in 2002 that they needed to implement a strict drug testing policy. Whether or not Major League Baseball would’ve reached this conclusion on its own or when they would’ve reached it is uncertain. Nevertheless, it’s interesting that a couple of U.S. senators got involved, throwing their political weight behind the issue. Is this an appropriate role for two government agents to play? This is perhaps a two-headed political theory question.

First, operating under the current federal law, many performance enhancing drugs or steroids are illegal when not obtained from a physician for a legitimate medical need. The government has the right and responsibility to enforce that law, both from a Constitutional standpoint and a biblical standpoint (Romans 13:4). But does the government have the right in this case to tell a private enterprise how it ought to conduct its business with its employees? Drug testing for private employees is not required by federal law. In fact, it can be viewed as an invasion of privacy (an issue the Players Association brought up when drug testing was first being discussed). I would argue that the federal government does not have the right to intervene into private business to tell them how to operate when they aren’t breaking any laws. The fact of the matter is it never came to this. Major League Baseball and its Players Association came to an agreement to begin drug testing independent of government interaction, but the fact that they stuck their noses in it should’ve raised some questions.

The second political theory issue goes deeper. As I noted, the Federal Government currently has the right to enforce laws banning PEDs, but should they have this right? An answer in the affirmative is something most people would probably take for granted, but perhaps it should be looked at more closely. Maybe it will be if Representative Ron Paul has been successful in bringing attention to a more libertarian perspective in government. A libertarian-like perspective on this issue could certainly be presented by fellow blogger Ryan who has presented a myriad of topics related to Two Kingdoms theology. If the removal of a federal ban on PEDs were argued persuasively, this would simply throw the question back into the private arena. Ultimately, this is where the issue was resolved anyway, but again, there’s an opportunity there for a political theory discussion.

The notion of putting asterisks next to records is, I believe, silly and short-sighted. If the reports and testimonies of former players are to be trusted, perhaps more than half of MLB was using steroids. Offense was up virtually across the board. To denote certain records broken–or to strike them from the record books completely, as some have suggested–is an overreaction. And as the Roger Clemens trial continues, we’re reminded that it wasn’t just he hitters who were gaining an unfair advantage. The entire era is tainted by PED use. Just as baseball’s Deadball Era is remembered as a low point for offense, the Steroids Era will be remembered as a high point. As comedian Daniel Tosh explains, the Steroids Era wasn’t the only one in which would-be record breakers had an advantage.

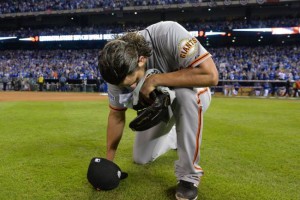

Linking the political issues and the baseball history issue is the collective reaction of the fans in the aftermath of the steroids revelations. The immediate reaction was almost universal disapproval. The cry from fans everywhere and from the greater society was that these players were cheaters. They had tarnished the record books and disrespected the game itself. I believe this feeling comes from a deep-rooted desire for justice, which though tainted by sin, is part of being made in the image of God. I find myself sympathetic to this reaction, but not entirely offended by the actions of the PED-using players. As previously discussed, steroids were prevalent throughout baseball to the point that it characterized an entire era in the game. It would be far more egregious in my mind if only a handful of players or a particular team had an unfair advantage (The economic inequity in MLB causes be greater consternation, but that’s a topic for another discussion.). The allegations of NBA referees throwing games by former referee Tim Donaghy seem to me to be a far greater scar on a professional sports league because the playing field cannot in anyway be considered equal in such a case. Unlike with PED use of Major League players, the advantage gained in such a situation do not even out.

Another part of the public outcry was about the danger of steroid use. A series of public service commercials have aired over the past few years warning kids about the damage steroids can do to the body and about the cheating stigma attached to their use. The fear is that young aspiring athletes might follow the example set by some professional athletes and open themselves up to these dangers. This is definitely a legitimate concern. Do a Google search for “steroid side effects” and you can see where the concern comes from. But it’s interesting to note from a sociological perspective the morality of the culture we live in. Based on the collective reaction to the steroids scandal, it seems our society deems cheating immoral. It also deems PED use wrong because of the physical danger it poses. This dislike of physical dangers is also present in the society’s approval of laws banning other harmful narcotics. The evidence for the harm these things do is tangible. Contrast this with the society’s view of moral issues in which the harm caused by the actions are less physical than psychological or emotional. For instance, society was concerned with the example set by PED-using athletes; but there is no similar concern about the example set by sexually provocative and promiscuous pop stars. Judeo-Christian sexual ethics are now viewed as backwards and outdated by the society, but the Christian believes they were put in place by our Creator to maximize human flourishing and, thus, bring him glory. Isn’t there evidence to suggest the damaging effects of pornography or the breakdown of the family caused by childbearing outside of wedlock? Without veering off topic, all this to say, it’s interesting to observe the morality of society in the face of the Steroids Era in baseball being brought to light.

We’re now years removed from baseball’s Steroids Era. The excitement level at the time rivaled that of America’s other popular sports. The home run chase between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa in 1998 brought back fans who had left in disgust following the strike. The home run persuits of other stars helped baseball hold the attention of younger fans who were losing interest shortly after little league in favor of basketball and football. Whatever it represented while we were experiencing it, it probably represents something different now. If nothing else, the end of the Steroids Era offers a snapshot into American poltical and civil life. I might be the only one who finds that interesting, but in the absence of home runs, I have to find something to keep me interested in baseball.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.