Recently Harry Potter fans celebrated the arrival of the “nineteen years later” day from the epilogue on September 1st, 2017. Here’s an interesting write-up about this momentous occasion. In case you don’t know, this is the day that Harry and Ginny sent their son Albus Severus off to Hogwarts, which can be found in the epilogue from Deathly Hallows. For some fans, the epilogue stands as an important ending to the seven-part narrative, which provides a happy and hopeful note. Albus Severus may or may not be sorted into Slytherin, and either way that is totally fine. For fans who have read the script or have seen a performance of Cursed Child, the epilogue from Deathly Hallows is cast into a different light because of the trajectory that the story takes from there. We learn that actually, Albus and Harry have a strained relationship that needs to be rectified.

As you may know, I am not a fan of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. I’ve written a couple reviews already which you can check out here (“Some Initial Thoughts”) and here (“A Rantastic Review”). The bulk of my criticism boils down to the fact that the story doesn’t fit well within the seven-part story, and it doesn’t carry the original story forward (hence it should not be called “the 8th story,” even though it is marketed that way).

Well, you may be surprised to know, that I’ve had a change of heart. I have now come to the conclusion that the Cursed Child is, in fact, the 8th story. Allow me to explain.

You see, Cursed Child is a story about alternate realities. It openly explores new outcomes and consequences based upon changing the past. In fact, you could call it Harry Potter and the Butterfly Effect for the way it explores the implications of time travel and adjusting the past; even small and seemingly insignificant changes can result in massively different results. The story explores this in a number of ways, and if you’ve read the script at least you know that one of the altered realities – Spoiler Alert! – is that Voldemort takes over the world, and all people are subservient to his reign. Thankfully, this reality does not linger because, yet again, there are more adjustments to the past.

I’ve already argued that the mythology and mechanics of time travel in Cursed Child are noticeably distinct to, e.g., the Prisoner of Azkaban, where the past cannot be altered through time travel. In fact, at the Harry Potter conference at Chestnut Hill College last year I heard a great paper that got more into the weeds on these discrepancies.

But Cursed Child can be different. And that’s okay.

Here’s how I came to change my mind. Given that the story focuses considerable attention on how small adjustments alter the course of history, I was struck by the opening scene from Cursed Child (Scene One, Act One). If you’ve read the script for the play, you know that the initial scene is – as noted above – actually a recapitulation of the epilogue from Deathly Hallows where Harry and Ginny send off their son Albus Severus to Hogwarts nineteen years after Harry defeated Voldemort. So Cursed Child picks up right where we left off.

Or does it?

If you look closely, something is distinctly different between the opening paragraph from Deathly Hallows’ epilogue chapter and the opening paragraph of the first scene from Cursed Child.

A busy and crowded station. Full of people trying to go somewhere. Amongst the hustle and bustle, two large cages rattle on top of two laden trolleys. They’re being pushed by two boys, JAMES POTTER and ALBUS POTTER, their mother, GINNY, follows after. A thirty-seven-year-old man, HARRY, has his daughter, LILLY, on his shoulders (Cursed Child, p.7).

Autumn seemed to arrive suddenly that year. The morning of the first September was crisp and golden as an apple, and as the little family bobbed across the rumbling road toward the great sooty station, the fumes of car exhausts and the breath of pedestrians sparkled like cobwebs in the cold air. Two large cages rattled on top of the laden trolleys the parents were pushing; the owls inside them hooted indignantly, and the redheaded girl trailed tearfully behind her brothers, clutching her father’s arm (Deathly Hallows, p.753).

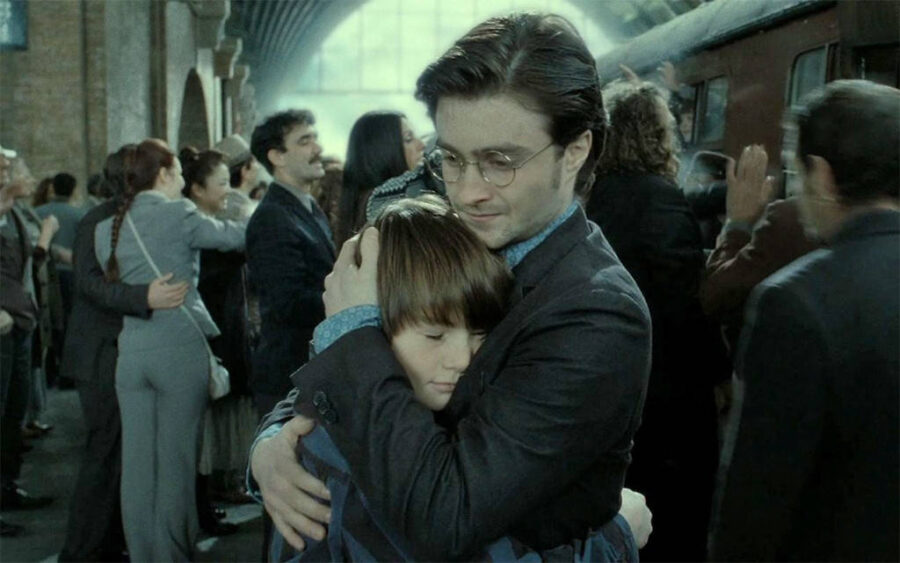

Notice this: who pushes the carts in Deathly Hallows and who pushes the carts in Cursed Child?

The answer to that question, I submit, determines the canonicity of Cursed Child.

Here’s how I see it. There was a tear in space-time that began with Harry’s decision not to push his son’s things to King’s Cross. In one dimension – the dimension where the story of the Cursed Child never happened – Harry pushes his son’s things. In the other dimension, he does not. All of Cursed Child is the result of Harry’s decision not to push his son’s things to the front of King’s Cross station, creating emotional uncertainty in young Albus at this moment of acute insecurity.

Thus, Cursed Child is the 8th story if Harry does not push his son’s things, and alternatively, Cursed Child is not the 8th story if Harry chooses to push his son’s things.

My suspicion ultimately is that the play takes off as it does because the source materials are the films rather than the books. The final film also has Albus Severus pushing his own cart. But this only further demonstrates the wedge between Cursed Child and the canonical books.

Finally, I submit, with tongue firmly in cheek, that Cursed Child is therefore the alternate reality created by Harry’s decision not to push his son’s things, which creates a topsy-turvy scenario that is not finally rectified until the end of the narrative, after other reality-altering events take place. Cursed Child is itself an alternate reality, showing us what happens when fathers do not support their sons. Thankfully, Harry is a supportive father and Albus Severus went off to Hogwarts feeling secure in his identity no matter what the Sorting Hat may have said when he arrived.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.