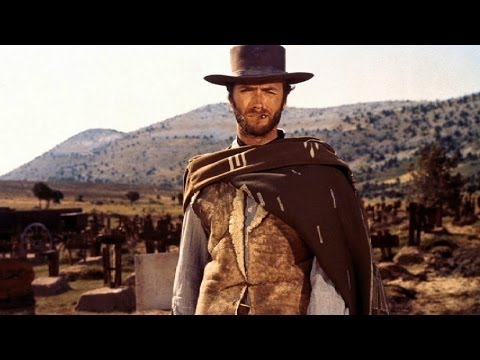

We don’t live in a Western film. You know, the one where the good guys wear white and outshoot the dastardly villains in black? That kind of world in which exist only the good, the bad, and the ugly, is not our world. It would certainly be easier if the true villains of our world’s problems wore certain types of clothes that were indicative of their evil disposition. (Why is it usually black?). It would simplify our most complex geopolitical, humanitarian, philosophical, scientific, ethical, or theological issue if the good guys and their easily understandable solutions just declared themselves to be the good guys and wore their own respective get-up. (And does it have to be white?). But even Westerns aren’t this simple.

The good guys and the bad guys aren’t always what they appear. Often, the local sheriff of the town has been bribed or intimidated by the outlaws into not doing his job. He is corrupt, and the man who ought to have been the good guy isn’t, hence the need for our gun-slinging hero. But, who are the good guys in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid? Well, it’s not our outlaw protagonists, that’s for sure. Is there anyone truly good in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven? Our perspectives in film, as well as life, are usually limited, biased, and short-sighted, but they don’t have to be.

The story of Judges 19-21 reads like a Western gone wrong. The good guys become the bad guys, the bad guys become the oppressed, and reconciliation only occurs when the two sides oppress somebody else. The story of these chapters is shot with a wide-angle lens that has a Levite almost brutally raped by a gang of thugs in a Benjaminite town called Gibeah. After escaping, he sends out a call to arms and all of Israel responds with aid. (Just like Rohan responds to Gondor). After some rather brief peace talks, the Benjaminites refuse to surrender the culprits, so a civil war erupts that results in the near annihilation of the tribe of Benjamin. Israel quickly realizes their mistake—they just nearly destroyed one of their own people groups—and they seek to reconcile. Thus, they try to find some wives for the remaining 6oo men of Benjamin to repopulate their tribe. However, the drama ensues as Israel had previously made a vow to not give their women to the Benjaminites (I know, a weird vow to make). Yet, the newly reconciled tribes find a loophole that allows the Benjaminites to simply steal the women. After a rather unceremonious, state-sponsored kidnapping/wife-grabbing, the story ends with everyone living happily ever after.

So, who is the victim here? Who are the good guys and who are the bad guys? Whose story is it? My telling of Judges 19-21 leaves out an important character that provides the clue to this answer. You see, the Levite was actually traveling around to win back his concubine who had run off in anger (we aren’t told exactly why, but it couldn’t have been good). His intention—one which he never fulfills—is to speak to her heart. Once she is secured from her father’s house, the Levite travels towards home but must find a place to lodge for the night. His remaining options are the foreign city of Jerusalem (it wasn’t always the Israelite capital) and the friendly town of his countrymen, Gibeah. After he finally secures boarding with an elderly man (or an elder of the city), it seems that all is well—until the knock on the door. Akin to how the bad guys wait outside for the showdown, the troublemakers in Judges 19 are calling for the elder so release the Levite to them. If this was a true Western, you would expect our gunslinger, the Levite, to open the door and face these hell-raisers. But this ain’t no Western.

Instead, the Levite opens the door only to thrust his concubine out to be raped and abused in his place. After a traumatic night, she collapses on the threshold, only to be commanded by the Levite to get up to return home. She does not answer (In the Greek version of the text it says that she was dead), and upon returning home, the Levite cuts her into twelve pieces and sends her throughout Israel. At the end of this traumatizing, terrible, tragedy (and every other fitting word), the narrator breaks in with three imperatives for the reader: “Consider her. Take counsel. Speak.”

Yet, the people of Israel neither had, nor heeded these words. They saw her body but did not know her story. Instead, they went to war out of vengeance at the testimony of the Levite regarding his murdered concubine. And it’s always about a girl, right? Well, it’s not always about a girl in the same way. Forgive my abrupt scene change, but this is not Troy in the Iliad, this is Gibeah in Judges. This woman is not some beautiful princess, she is a slave; she is not whisked away by a goddess, she is butchered by her “Man.” This woman and the other women of the story do not speak, nor are they heard or properly considered. They are only destroyed. In this story, bad only gets to worse, and goodness is palpably lacking. The Concubine is marginalized in both her life and her death. What results from this marginalization is only more violence, massacres, and marginalization. Because they did not listen, more people suffered and more people died.

This story raises a lot of questions for me personally. It’s not pretty and sometimes it’s pretty hard to look at. But I believe this gruesome story illustrates the dire importance of listening to the voices of the marginalized. When we fail to listen to the whole story, skipping over the voices we deem less important, only harm can come. This is our reality in today’s world. There are so many issues that demand our attention, but it is often hard to cut through all the noise to hear the stories of the marginalized, maligned, and oppressed. But we need to. We need to stand up and pause the conversation long enough to hear the whole story. We need to withhold our judgment and take counsel with each other—holding conversations and dialogues that aren’t just shouting matches. We must finally speak to these issues. We cannot stay silent about injustice, but we must use our voices, as well as our actions to advocate for the marginalized. I certainly don’t have all of the answers, but here are three areas that I have been processing through recently in my journey to learn how to hear the marginalized.

Consider: The Anabaptists

I’ve been hearing a lot about the Anabaptists recently and I realized that I know nothing about them! I’ve come across them in my reading of the Reformers, but they were simply dismissed as heretics. I’m reading The Anabaptist Story by William R. Estep, and it is heartbreaking. First, the majority of the groups that are categorized under the umbrella term of “Anabaptist” weren’t heretics in an orthodox sense. They believed in the Trinity, Jesus’ atoning sacrifice, salvation by grace through faith, etc. Second, the main point of contention in their theology is that they disagreed with both the Catholic Church and the Reformers in their belief of infant Baptism. They held firmly to a believer’s baptism as they were convinced that only this type of baptism was found in Scripture. Third, they were staunchly Christ-centered. Their lives were directed by Christ’s example and they took his words, as well as the rest of the Bible literally (some of the various Anabaptist groups even created a community of goods in which they shared their possessions). They were non-violent and condemned the state church’s role in promoting or participating in warfare. Fourth, they were mercilessly tortured, beaten, and drowned. A number of their leaders and pastors were killed only after a few years of preaching. A number of them were drowned and others were burned at the stake. This is one story I had never heard.

Take Counsel: The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict

If you are anything like me, you perhaps grew up vehemently supporting Israel as God’s chosen modern nation-state and a precursor to the End Times, Armageddon, and the Second coming of Jesus. If you didn’t, well then you probably weren’t a dispensationalist. However, what I didn’t know growing up was that there was another side to the story, and it wasn’t a bunch angry Muslims bent on destroying Israel either. I recently was suggested Faith in the Face of Empire by Mitri Raheb. As a Palestinian Christian Pastor from Bethlehem, Raheb provides a unique perspective to this conflict. If you, like me, grew up learning that Israel can do no wrong and that all of their actions towards Palestine is justified, you will hate this book. I say this because I found this book challenged a lot of my preconceived notions of the Middle East and my views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This was another story I had never heard.

Speak: When _______ becomes more important than Black lives

These past few weeks have brought a lot of attention to race and ethnicity in America. Donald Glover’s “This is America” music video showed the ways culture has ignored violence by distracting itself with entertainment. The NFL announced that players must stand for the national anthem or be fined. This targets players who kneel to protest police brutality and racial injustice against African Americans. Again, this issue is complex. I recently read James Cone’s The Cross and the Lynching Tree. It was deeply powerful and heartbreaking. One of the eye-opening things that Cone discussed was the 20th-century theologian and ethicist, Reinhold Niebuhr. Cone valued much of Niebuhr’s theology, but his major critique of him is that he failed to speak about the oppression of African Americans. As much as Niebuhr spent time talking about the cross, he spent no time speaking of the lynching tree. This book is challenging as it reports stories of suffering, oppression, and the churches of white America’s less than Christ-like response. Yet another story I had never heard.

We must listen to these stories and others like it. We need to know the full picture. We don’t necessarily have to agree with everything that is said, but we’ve got to listen. We ourselves desire to be heard and understood, and thus we must extend this decency to one another. Yet, we cannot simply listen, we must speak and we must act.

1 Comment

Leave your reply.