I recently gave a devotional for student success advisors at Bethel, and I wanted to share a portion of that reflection here. In the midst of this coronavirus situation we’re all obviously impacted in some way, maybe not necessarily physically or financially just yet, though that could come, but we have all experienced disruption to our routines and rhythms.

As a result, we all have so many shared feelings and shared experiences right now:

- We all long for normalcy.

- Our productivity is down and our diets are out of whack.

- The only days of the week that are relevant anymore are yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

- Toilet paper is currency.

- Sweatpants have become work attire.

- We miss giving and receiving hugs.

- We long to once again spend hours chatting with friends at noisy coffee shops and breweries.

- We’ve had trips, events, and conferences canceled.

- And we all think that Carole Baskin killed her husband.

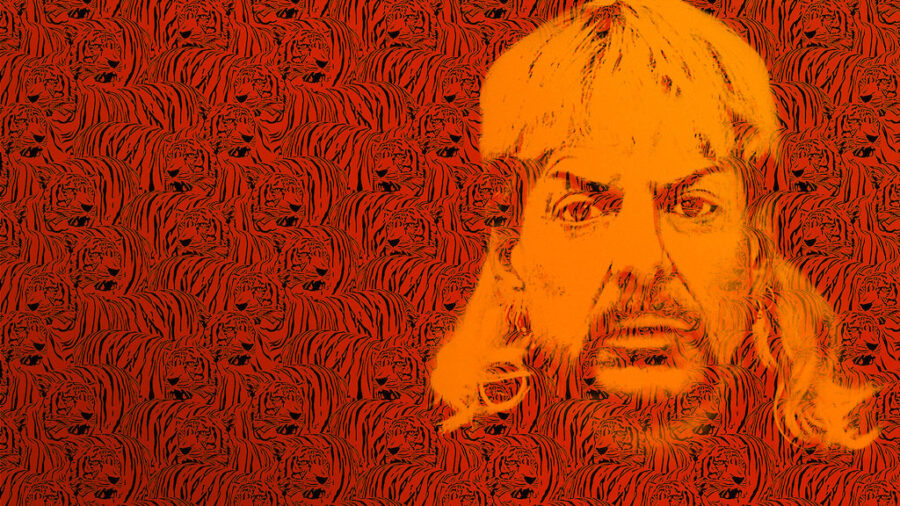

To say that the Netflix documentary Tiger King has been a major sensation is the biggest understatement of 2020. If you’re not familiar, Tiger King is a docu-series about Joe Exotic and other wild characters in the big cat industry in America. I wonder if at least part of the reason why it’s so popular is because during our days of quarantine we resonate with those Tigers locked away in cages.

But perhaps the aspect of the show that everyone’s talking about more than anything is whether the owner of Big Cat Rescue was in some way responsible for the death of her husband. And that fact has me reflecting on the ethics of how we tell true crime stories.

For some broader context, Netflix is famous for true crime documentaries, most notably Making A Murderer. In the attempt of the filmmakers to call into question whether Steven Avery was wrongfully convicted of murder, the series ends up pointing the finger in several other directions. There’s a kind of cavalier way that Making A Murderer relays the information in the most gripping way possible, which causes the viewer to assign horrible motives and intentions to the police department of Manitowoc, among others. Each episode gives you just enough evidence to cast suspicion at a new potential suspect like any good Who Done It mystery… Except, these aren’t characters in a mystery crime novel; these are real people. And so what scores for good mystery, has real life ramifications.

There is at least one docu-series on Netflix that actually directly addresses the responsibility of those who tell true crime stories. That show is American Vandal. I need to say very clearly that, if you know anything about this series, this is admittedly the least likely place to receive this kind of message perhaps. It is a parody of true crime, more of a mocu-series. It is quite crass. Think High School locker room humor. Frankly, as crass as crass can get. Scatological is perhaps the best word for it. American Vandal is a self-aware, self-critical mockumentary. Taken as a whole the show shines a light on the ethics of true crime, and specifically the ethics of Netflix’s brand of true crime. In my opinion American Vandal does this profoundly; frankly, I was genuinely convicted by the end of it.

A recent documentary on Netflix also seemed to be mindful of this critique and attempted to incorporate it at the last minute. And that show is Don’t F*** with Cats. It’s a true crime docu-series about heinous animal abuse of cats. The show receives it’s title from the so-called “Rule 0 of the internet” which is that you don’t f*** with cats. It’s a docu-series about an animal abuser turned murderer, but it’s more fundamentally about the Internet community that somehow tracked this man as part of a real life cat and mouse game between the internet community and the culprit.

At the end, one of these internet community members considers her own culpability. Did she along with the others in this online community unwittingly egg him on? Were they responsible for getting it wrong in the past when they suspected someone else all too quickly? If so, would she personally be culpable in some way?

She never answers this question, but instead draws the viewer in at the end and tries to probe our own culpability—are we as the viewer off the hook? It’s a great question, but in this show it does not at all feel earned. It came across like blame shifting or an example of what-about-ism.

So returning to their newest documentary, Tiger King, Netflix speaks out of the other side of its mouth. They do not seem to be mindful of these earlier admonitions from American Vandal or Don’t F*** with Cats when they allows us as the viewer to swiftly conclude on Twitter and TikTok that Carole Baskin killed her husband.

What makes the posture of the filmmakers towards this possibility even more problematic, are the auspices under which the filmmakers came to the Baskins, which Howard Baskin explains in a recent recording on March 28th.

As Howard explains in the video above, the Baskins thought that they were participating in the big cat-equivalent of The Cove, the animal rights documentary about dolphin hunting off the coasts of Japan. At the end of the video Howard concludes rather pointedly by making the comment that the final cut of Tiger King seems to be fundamentally exploring the various con artists of the big cat industry—Joe Exotic, Carole Baskin, Doc Antle, and Jeff Lowe, etc. But the biggest con artists of them all, Howard explains, are the people who made the documentary under false pretenses.

For us consumers in quarantine, the idea that Carole Baskin killed her husband is worth a few good memes, celebrity tweets, and entertaining debates over FaceTime, but what does it cost for the Baskins?

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.