What does it mean that the “word of God is living?” That’s a big question, but I will only focus on one part. I think that it is of fundamental importance to recognize that, in every day speech, there are two very different sorts of existence that we describe as “alive.” Before we apply the label of “living” to a text we have to decide what sort of living thing it is. These two sorts are personal and impersonal existence. They are of course very, very different, and these elaborating on these differences will helpfully accentuate the importance of how we use our terms.

Many, many things are alive and are not persons. Some of these things are unwieldy and dangerous, like a rabid dog, but as humans we have learned that nearly all impersonal living things can be tamed, controlled, corralled, or killed. Impersonal life is malleable. We can domesticate the living in order to serve our own ends, and to the great benefit of ourselves and our neighbors. Think of the cultivated seed, made immune from the usual ravages of the natural world, placed in the ground, and bearing fruit a hundred fold. This care and use of the living is what human beings do (how ethically, of course, is another question). Everywhere we find ourselves nurturing, developing, improving, subjugating. We speak to impersonal life; it does not speak back. Impersonal life exists, in this context, to be both the object of our care but also as a resource to be harvested. Its purpose is found in its utility, and when that utility is compromised or lacking impersonal life can be modified, ignored, destroyed, or discarded.

I fear that it is in this sense of “living” that we usually think of living texts. Consider the Constitution of the United States which is routinely referred to as a “living document.” What is usually meant is that the Constitution exists for the sake of the people, and not vice versa. As alive but impersonal, the Constitution is framed in contemporary discourse as a life that adapts to the needs of the moment. As Woodrow Wilson said, “…Government is not a machine, but a living thing. It falls, not under the theory of the universe, but under the theory of organic life. It is accountable to Darwin, not to Newton.”[1] Evolutionary. The needs of the moment, however, are not created by the brute and impersonal forces of nature but by the shapes and contours of society. We might think of the Constitution is a seed to be nurtured by society for its own benefit. In this way, the individual exists under its authority, and yet never fully so because the individual, as a member and shaper of society, always stands with the potential for change. She is always nurturing, developing, improving, and subjugating. The real important questions in such a state of affairs really circle around the felt needs of the wider culture rather than what the document has contained for past readers. This is true of either side of the political spectrum. The final question is always, “What kind of society do currently exist, and how do we want it to exist in the future?” rather than “What does this text contain?” We speak to the Constitution, and if it speaks to us it says exactly what we have designed it to say.

This however, is not the only way that something can be alive.

The second kind of life is personal, and therefore is very, very different from what I have discussed thus far. Personal life ought never stand before us as an “it,” or a “what,” but as a “who,” even a “thou.” Whenever we engage with a person in other terms we risk doing great violence and harm. Taken to extremes, we ourselves, as persons, stand violently opposed to what we truly are. Persons cannot be regarded as objects to be cultivated to meet personal needs, and they cannot be valued merely based on utility. Most importantly for the present discussion: they speak to us and we must listen. In some cases, such as with children, this listening also involves correction and instruction. In other cases, such as with peers, this creates dialogue, mutually beneficial discussion, and collaboration. But in other cases, as when we speak with one in authority, we must listen, seek to understand, and to obey. Authoritative life speaks to us in a way that we cannot control or change. This does not mean that we lose the ability to disobey, forget, or manipulate the message, but these options disappear in the presence of the authority. To stand before a living authority requires radical engagement with an existence apart from our own that makes demands of us, calls us into question, and moves us towards obedient action.

All human relationships, including those who stand in authority, will involve a mixture of responses. I certainly wouldn’t say that all human authorities, as authoritative persons, are to be always heard and obeyed. But when Hebrews 4.12 tells me that “the word of God is living” we have to make a conscious decision: what kind of life does this word have? When we encounter this living word we must make a decision: is this life impersonal or personal? If it is personal, does it stand as one in authority or is it my peer, engaging me in debate, dialogue, and disagreement? If it does stand in authority, how do I respond and obey?

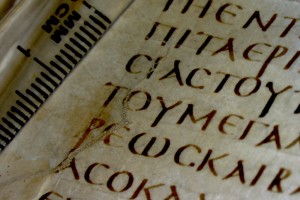

My only goal in this post is answering the first question. There is no doubt in my mind that if the Bible contains the words of God, and those words are living, then they are the personal words of an authoritative person. We commit a huge error when we take the language of “a living document” or “living words” and turn it into a license to treat God’s words as impersonal, evolutionary, and designed primarily to be shaped by the needs of society to meet the needs of society. The Word of God is living and active, and He is not a domesticated animal.

[1] Woodrow Wilson, Congressional Government in the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 1908), 56.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.