Happiness on earth, friends, only stems from war!

Powder smoke, in fact, mends friendship even more!One in three all friends are: Brothers in distress,

equals facing rivals,

free men – facing death!

In this text, Nietzsche begins with an assertion that war is the only source of happiness. Then, after claiming that the action of war only enriches friendship, he parodies the Aristotelian tradition by listing three ascending levels of friendship that are affected by war.

Nietzsche disagrees with Aristotle on two fronts. For one, Aristotle believed that humanity was fundamentally political, and that our happiness goes hand-in-hand with well-ordered political community. Nietzsche thinks that political order is a social construct that contradicts and constrains our drive for freedom. And for another, the three categories of friendship Aristotle identified are morally positive; although some are more virtuous than others, each of them is good. Nietzsche, on the other hand, lists a negative, a neutral, and a positive tier of friendship. Friendship, for Nietzsche, is a qualified good; only the friendship of wartime “free men – facing death” will make us happy.

Although the Christian tradition of friendship borrows extensively from Aristotle, this fragment draws out some surprising features of Christian friendship.

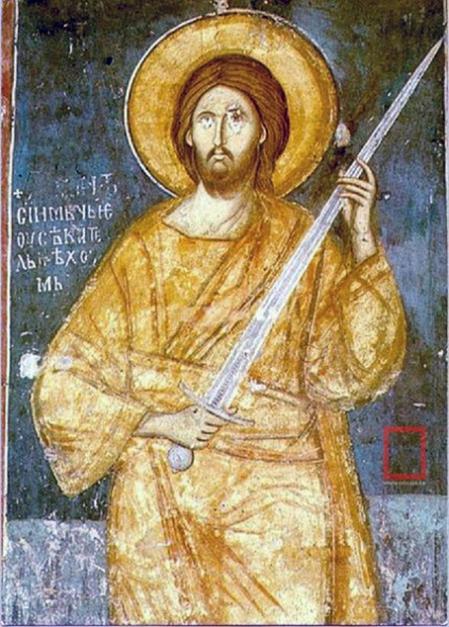

Jesus’ Nietzschean Happiness

Nietzsche’s three categories of friendship, “distressed brothers, equals, and freemen,” are static. At a given point in time, two men fall into only one of the categories, and so their friendship can be considered negative, neutral, or positive, respectively. But such static categories aren’t necessary. Over the course of time, two friends could move from the place of being distressed brothers, to being equals facing a common rival, and then facing death as freemen. Over the course of his earthly life, Jesus ascends the Nietzschean ladder of happy friendship.

In Matthew’s account, Jesus’ very sending of his disciples incites violence. He gives them “authority over unclean spirits, to cast them out, “and he expects they will be “dragged before governors and kings… Brother will deliver brother over to death, and the father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death, and [they] will be hated by all for [his] name’s sake.” (10:1, 18, 21-22) Lest anyone mistake him, Jesus says himself: “I have not come to bring peace, but a sword.” (10:34) Jesus’ friendship with his disciples stems from war and is “mended by powder smoke.”

Over the course of his life, Jesus assumes all three modes of Nietzschean friendship, in ascending order. And the author of Hebrews notes all three in the same paragraph:

- Distressed brother. Although Nietzsche doesn’t count this a happy friendship, it counts as friendship nonetheless. And it’s a mode of friendship with which we are familiar and of which we more commonly approve. If Jesus were going to become friends with us who are distressed, he had to take the form of a distressed brother, emptying himself of his power. “Since therefore the children share in flesh and blood, he himself likewise partook of the same things… Because he himself has suffered when tempted, he his able to help those who are being tempted.” (2:14, 18)

- Equal facing rivals. Rather than succumb to the weak condition of sinful flesh, Jesus suffered the temptation that is common to man so that he could be made a priestly friend. “He had to be made like his brothers in every respect… Because he himself has suffered when tempted, he is able to help those who are being tempted.” (2:17)

- Free men facing death. But Jesus both overthrew death and delivered his friends from it. “Through his death he might destroy the one who has the power of death… and deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong slavery.” (2:15)

By his exemplary, victorious, and substitutionary death, Jesus converts his followers into “free men facing death.” The way Maximus the Confessor puts it, I can’t imagine Jesus wanting anything less for the ones whom he called his friends:

Those who innocently endure death amid voluntary sufferings for the sake of truth, and who have become heralds of the message of grace, continue to bring about life in the Spirit for the Gentiles through knowledge of the truth. [This grace is] God’s gift since it bestows the light of true knowledge, and furnishes an incorruptible life for those who receive it; God’s labor because it convinces its servants to take pride in their own labor on behalf of the truth, and teaches those who are too anxious about their life in the flesh to extend themselves more through suffering than through remission of suffering.

Asceticism in Christian Friendship

According to Maximus, this freedom from the tyranny of death is best expressed through asceticism. While our freedom from death depends not on our works, but on Jesus’, our participation in that freedom requires suffering. And if the suffering doesn’t come from external sources, suffering must be voluntarily chosen. Hear this other blogger’s reflections on Nietzschean friendship.

Today it is mostly understood that a friend is someone ‘who wants the best for you.’ Nietzsche considers this too shallow and his response is similar as in the case of the Christians who would like to live only in their ‘heaven.’ A true friend for Nietzsche is someone who by wishing you the ‘best’ wishes you ‘the worst,’ – struggle, strife, obstacles, fear, and ‘many good enemies.’ A friend for Nietzsche is not someone who accepts your every word and blindly follows in your steps or even someone who tries to ‘offer you a helping hand’ – this only promotes laziness, acceptance of one’s status, weakness and decadence. To wish truly one best also means to be in opposition, to propose contra-arguments, to go one’s own way and even destroy and fight against a friend’s plans. In the Nietzschean sense, the friend is the one ‘who wishes you to be strong.

Not surprisingly, Nietzsche doesn’t make his point tactfully or with sufficient theological nuance. While we do not categorically oppose our friends, we would do well to oppose them more often than we do. By calling them to suffer, we call them to participate meaningfully in their union with Christ. If we “suffer the loss of all things and count them as rubbish… we may know him and the power of his resurrection… sharing in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, that by any means possible we may attain the resurrection of the dead.” (Phil. 3:8-11)

As the light of Christ continues to shine in the darkness through the obedience of his body, “powder smoke” may indeed mend many a friendship.

(h/t to Ian Heisler for discovering the Nietzschean fragment quoted above.)

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.