As the lockdown to prevent the spread of COVID-19 drags on, questions regarding the nature and place of the Eucharist are becoming more and more important. Christians in all traditions are now forced to grapple with the reality that it may be some months before congregations and church families can meet again in person. Churches have had to scramble to figure out how they can keep on meeting, many turning to digital mediums like Zoom or Facebook Live to do so. However, the issue of whether the Eucharist may be celebrated by all members of the congregation in their homes remains hotly debated.

There have been numerous publications and podcasts on this topic, the Two Cities not excluded (Listen to part 1 and part 2 of our discussion on the validity of virtual communion). Space precludes me from addressing all of the resources, but I will include them in a ‘further reading’ list at the end of this article. My aim here is to speak into my ecclesial context–the Church of England (You can read the Archbishops’ statement here,my Bishop’s statement here, and a nice paper from the London College of Bishops here). Hopefully, the points made here can also speak into other ecclesial situations and traditions.

I believe there is a good case to be made for celebrating the Eucharist with bread and wine in our homes, making every effort to observe the sacrament with reverence and in unity. I’ll discuss the particulars and the practicalities later in the article, but first, the case against my view.

The Case against Virtual Communion

One of the recurring arguments I’ve seen against partaking in the sacrament during this season of isolation is that by nature, the Eucharist is a corporate event for the gathered church. Many have cited 1 Corinthians 11 and Paul’s repeated use of “coming together” as biblical proof that the Lord’s Supper must be celebrated in the same physical space by a local church. Because the church cannot meet together physically, they cannot celebrate the Eucharist. Now generally, I would wholeheartedly agree with this, but it plays out a bit differently in the context we find ourselves in. These arguments also focus on the physicality of the sacrament to explain how virtual gatherings do not count in this regard. The premise upon which these arguments are built is the belief that human presence cannot be mediated through a digital medium in a meaningful sense. Live streaming a service or having a Zoom call do not function in the same way as a physical gathering. Thus, as the church is not gathered physically, neither can the Eucharist be experienced.

This is obviously a very simple and generic version of the argument against virtual communion, though I believe it is accurate (and convincing at times!). It must be acknowledged that being physically gathered with the church is far better than gathering digitally. During this time of isolation, the pain of being physically absent from loved ones, friends, and church family is acutely felt. As a raging extrovert, isolation is very un-ideal for me. As the church cannot meet, it seems our options are pretty limited. We can either hit pause as global church for the first time in our history and not continue to meet (This point is better-articulated by Ephraim Radner), or we can decide to “meet” in a ‘less than ideal’ manner, recognising that it is only a shadow of the experience. Most churches have opted for the second choice. Yet, in their practice, they are selective of what parts of a worship service ‘count’ as meaningful (e.g. the virtual gathering is not ‘real’ enough to qualify for the Eucharist, but one may still engage in sung worship and listen to a sermon through a digital medium). What these options and explanations miss, however, is the mediated reality of human experience. If one wishes to argue that human presence cannot be mediated digitally in a meaningful sense, they must then define what counts as meaningful presence in a mediated reality.

The Boundaries of Mediated Presence

All of human experience is mediated. Reality is mediated to us through our senses. Our social interactions are mediated through language–both spoken and shown in the body. One’s presence may even be mediated through the language of other people. For instance, a king’s presence (and the authority that comes with it) has been conferred through messengers and representatives. In a religious sense, the presence of a deity can be mediated through images/icons and the presence of the people may be mediated through priests. In the Old Testament, figures like Abraham and Moses, priests like Aaron and Eleazar, and prophets like Elijah and Isaiah, all were mediators who stood in the breach between God and the world. In a Christian framework, these actions coalesce in the person of Jesus Christ–who represents both God to man and man to God.

Symbols may also confer one’s presence across long distances: The signature of a king, itself just a recognized set of squiggles, may convey his pardon to a criminal. A mother’s heartfelt letter to her son on the battlefield (also just lines and squiggles) may bring him comfort in perilous times. All of our experiences of reality and our attempts to share these experiences with others are made possible through mediation. As Humans, we have been quite comfortable with our mediated experience of reality and presence.

Throughout history, our way of communicating has also changed mediums many times: from oral tradition to written, from the hand-crafted illuminated manuscripts of the medieval period to the mass-produced Bibles and pamphlets post-Gutenberg. We’ve gone from the Telegram to the Telephone, from Texting to Facetime to video conferencing with multiple people all across the globe. All of these communicative mediums mediate the human presence to another individual or group.

There is no doubt that some of these mediums are more effective in mediating presence than others. Why is this? Perhaps it has something to do with how personal the medium is. A phone call can be more personal than a telegraph. But it is not always the case that the latest technology is more personal or is more efficient at mediating presence. Some might still prefer a handwritten letter than a video call. A letter, while not as effective at mediating one’s presence as a video call, can still be intimately personal.

As Humans, we have been quite comfortable with our mediated experience of reality and presence.

Let me share a brief anecdote that illustrates this point. On my government-approved daily exercise, I happened to walk past my friend’s house. I knocked on his window, took several steps backwards, and waited for him. He saw me and, after cracking his window, we chatted about all sorts of things. What struck me about this conversation is that though it felt different than talking to the same friend via Facetime, our experience wasn’t much different. There was still a layer of glass between me and him. I had trouble hearing him sometimes, but I smiled and pretended to hear. There was also glare on the window, so I could only really see the upper half of his body. Is there a qualitative difference between all of these mediated interactions? Can we place them on a spectrum or graph to determine which medium is more personal and/or effective? Probably, but my point is not that there are better mediums or technology that mediate human presence, but that all human presence is mediated. The question remains: what counts as meaningful?

I don’t believe we can answer this definitively, at least not here in a blog post. I do not expect anyone would say that the conversation I had with my friend didn’t ‘count’ because of the limitations. Neither would I expect that anyone believes that video call with your family is the same as talking to a very expensive rectangle. Though we might personally prefer certain mediums of mediation, we cannot deny that human presence is being mediated in some way or another. If we accept this premise, then we can say that although we are physically separated, we are still able to gather through digital mediation.

One’s subjective experience of what medium is both personal and effective at mediating human presence cannot be definitive for the Church. You may find watching a church’s livestream very meaningful, others may not. I think there’s a correlation between the significance of mediated presence and how connected one is to the individual or group. A letter from my Grandma means a lot to me, but probably not a whole lot to someone who doesn’t know her. In a similar way, a live-streamed church service is probably more meaningful to someone who normally attends that church, is connected to the life of that church, gives to that church, etc., than someone who lives on the other side of the world and happens to find it in a google search. So again, the qualitative difference between the different mediums is subjective. Which mediated presence ‘counts’ as meaningful enough will be up to individuals and communities of faith.

To summarise so far:

The human experience of reality is mediated through a variety of mediums. Human presence is able to be mediated through these same mediums even when they are not physically present. The qualitative difference between the various methods/mediums is subject to a variety of reasons that differ from person to person. Therefore, it is possible to gather in ways other than physically, even if these other ways may be less meaningful or less personal.

It is possible to gather in ways other than physically, even if these other ways may be less meaningful or less personal

The Eucharist as Mediated Presence

There are others who might still pushback against celebrating the Eucharist despite acknowledging the ability for us to gather digitally. They might argue that the Eucharist is particularly physical––it is the physical act of sharing particular physical elements. So it is not the inability of a physical gathering that precludes us from partaking in the Lord’s Supper, but the particular physicality of the meal itself that precludes such a practice. While I generally agree with many of these points, I believe that those who make such an argument miss the mediated reality of the Eucharist itself.

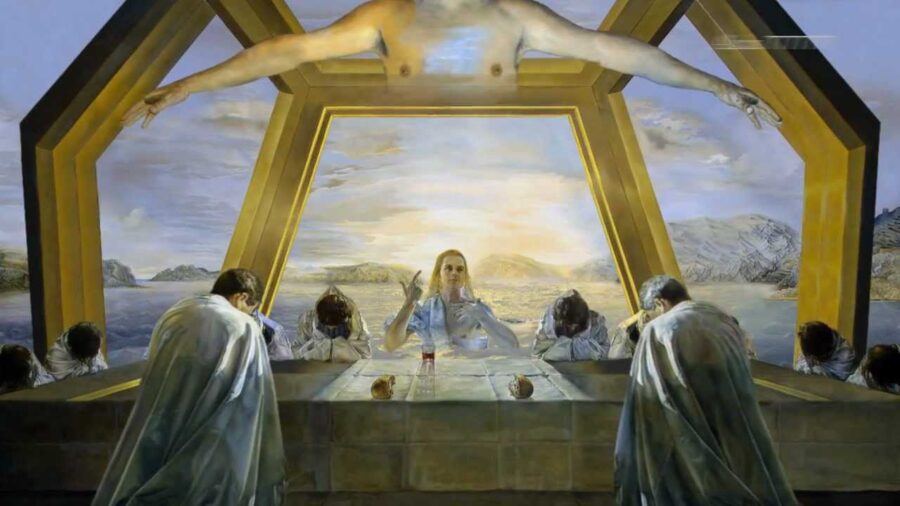

When the church meets normally, we celebrate the Eucharist by partaking the bread and wine. In this service, the elements become more than just common bread and wine, they communicate and mediate the real presence of the risen Christ. (The Catholic understanding would be that the elements are translated physically into Christ’s actual body and blood). We can say in faith, that the risen Christ is truly present in this meal, even though all we see and taste are bread and wine.

Not only is Christ’s presence mediated to us in the meal, but also time and space. This meal we experience in the present actually encompasses both the past and the future. We as communicants experience afresh Jesus’ final meal with his disciples. We reexperience through the repeated words and actions of Jesus that exact meal that occurred in first-century Jerusalem. Like the second generation of Israelites who heard Moses’ call to remember the mighty acts of God of which they never experienced, so we too actively remember and participate in a meal which we were not physically present for. In this meal, the future is opened to us well. It is a foretaste (an appetiser if you will) of the meal we will enjoy in the new creation with the Risen Christ and his Bride. This future meal will likely (hopefully) consist of much more than just bread and wine, but it will be the consummation of God’s mission– that we would dwell in perfect unity and love with God once again. This meal will be physical and unmediated in the way that it occurs on this side of eternity. The moment the bread and the wine touch our lips, the past and future are consolidated in the present––The Lord is here; His Spirit is with us.

Thus, the Eucharist is both intimate and mediated. It is truly a mystery of how such intimacy can be accomplished in the mediation of such common elements. But nonetheless, it happens every week (perhaps everyday) all across the world. It is no less remarkable than the incarnation, where the fullness of God (Col. 1:19) and the exact imprint of his nature (Heb. 1:4) were mediated by Jesus Christ. Though divine he was in human likeness, and though human, he was truly God. So, can this same mystery occur in our homes when our own presence and unity is mediated through digital technology? My answer is yes.

My Proposal

If we accept that human presence can be mediated through technology, and that, in the Eucharist, we can experience the mediated presence of the risen Christ, then we should be able to partake in the physical elements in our homes while watching a service of Holy Communion.

So how can this work? The best option would be to use Zoom (or some other video conferencing platform) and all partake of the elements together. This way, we could all see each other, respond to the liturgy, say the peace, etc. This would ensure that we are all taking the Eucharist together. Each member would have their own bread and wine and the priest may still say the words of institution and consecrate the elements. The effect for those watching is that their elements also are consecrated.

This option might not work for larger churches and it may be preferable to live stream or pre-record the entire service. In this instance, the minister would offer and partake in the Sacrament as part of the service. Those watching from home would partake at the appropriate time in the service. In order to maximise the ‘live’ experience, churches should do their best to watch the service together at the same time. This can be accomplished through Facebook Premier or Facebook Live (or a number of other ways that can stream the service a particular time).

In both of these situations, the presence of God is mediated to us in the elements and our human presence is mediated to one other through technology. It is much more than looking at a fancy rectangle––we are truly gathered and can truly experience the risen Lord. It is in faith that we can declare that The Lord is here. Even in our homes, His Spirit is with us.

Objections and Limitations

I can already imagine a whole host of very warranted questions and objections to my proposal. Let me respond to them, and if I have missed any, please let me know!

What about 1 Corinthians 11?

As I explained above, Paul’s prescriptions and prohibitions concerning the Eucharist in 1 Cor. 11 form the basis of many people’s objections. The repeated phrase, “when you come together” seems to indicate that the physical gathering is a necessity when celebrating the Eucharist. However, this is precisely the opposite point that Paul is making! The issue is not that the Corinthian church is failing to gather physically, but that they are failing to gather in spiritual unity. It even says in verse 20, “When you come together, it is not the Lord’s supper that you eat.” It is likely that the more wealthy and elite members of the Corinthian church went ahead with eating and drinking before the working-class Christians. When the day labourers and slaves showed up, they became intimately aware of the class differences and inequalities (This can be deduced from 11:21-22). Paul’s prescription then is that the Church waits for one another to eat the meal, but this is a remedy to their spiritual disunity. Thus, 1 Corinthians 11 has little to do with the physical gathering. Instead, it focuses almost entirely on the problems of spiritual disunity that may be rectified in part by physical means.

The issue is not that the Corinthian church is failing to gather physically, but that they are failing to gather in spiritual unity

A second response to this objection is a bit more cheeky. Paul did not have the internet. Paul’s instructions remain relevant for our context, but applying this wisdom and instruction is not as straightforward as some make it out to be. Paul is not prescribing a program here, but a communal identity centred on the love of Christ. Elsewhere in this letter, Paul will address other issues like marriage, eating food sacrificed to idols, and spiritual gifts. While he does give some specific directions in places, there is very little in these chapters to suggest a comprehensive program that we can replicate in our time (Hence the lack of consensus on some of these issues). Scripture must inform how we live, but its wisdom demands wrestling with how we ought to be faithful in the present.

How can we share in one bread and cup if we are physically separated?

This is a great question and is informed in part by the

Eucharistic liturgy that is similar in many faith traditions. Within the

service, the one who is presiding will break the bread and say:

We break this bread

To share in the body of Christ(All) Though we are many, we are on body,

becasue we all share in one bread.

So, how can we do this if we aren’t physically eating of the same bread and drinking of the same cup? Three quick response: Firstly, this obviously points to a spiritual reality. In no physical way are we ever ‘one body’ as the liturgy says. That’s precisely the point! We are many bodies but exist as one spiritually unified ‘body’ through our faith in the death and resurrection of Jesus.

Secondly, we also understand this act functions symbolically and we ought not to take it too literally. The global Church is unified in this practice, not necessarily in the breaking of the same bread. We wouldn’t (and shouldn’t) discount another church’s experience of the risen Christ simply because they were not in our building.

Thirdly, I wonder how many churches actually take this part of the liturgy as seriously as they are suggesting. Do you actually all eat from the same loaf of bread? Is there only one cup? My church buys those very tasty communion wafers that come 500 to a box––in no way are we physically sharing of the same bread. We also have two lines or stations so our service doesn’t last forever. For a number of churches, they might have two options of wine and grape juice to be considerate to those who struggle with addictions. In this case, there are not only two cups but two liquids! The same applies to those churches who also serve a gluten-free alternative. How about churches that have more than service? Now, I am in support of all of these options, but that’s because I believe that spiritual unity is what is important, not that we physically share in the exact same elements.

Can we use anything we want for the elements?

No. At the moment, there are enough resources for people to get bread and wine (or grape juice). There is no reason to change the elements, though there might come a time where resources are scarce. The church will have to reassess at that time. For the moment, please don’t try to take communion with sprite and cookies or whatever is in your cupboard.

Should we settle for less than ideal?

This is also a really fair question. As I mention, I think just about everyone would agree that gathering physically is far better than what we are doing now. Shouldn’t we then simply wait? Must we accommodate to our situation and settle for less than ideal? Another three quick points: Firstly, just because something is ‘less than ideal’ doesn’t imply that it isn’t meaningful or that we shouldn’t do it. Secondly, our typical experience of the sacrament is already ‘less than ideal’ in so many ways. If the early church is any example to us, we ought to be partaking in the Eucharist as part of a meal. This is simply not feasible for many churches due to socio-economic reasons, congregational size, or lack of building space. Thirdly, the Eucharist itself is all about ‘settling for less than ideal’ (though we might wish to phrase it differently). The Eucharist is a celebration and remembrance when God chooses to reconcile with Humans in the person of Jesus Christ. The gospel becomes about how Jesus eats with sinners and heals the sick and finds the lost. All of this is accomplished through the un-idyllic crucifixion. God is to be found in and among the ‘less than ideal’.

Should we call this an opportunity to fast from the Eucharist?

I have heard this suggestion thrown around quite a lot. To me, this sounds so weird (especially now that we are no longer in a season of Lent). Fasting is a wonderful spiritual practice that I definitely don’t do enough. Typically, we would fast from things that normally distract our worship or from things we rely on too much. It seems strange to suggest that we fast from a sacrament. It might be one thing to fast from listening to music but it is quite another thing to fast from worshipping! Imagine if one of your members said that he was going to fast from reading his bible or praying? Or taking it more spiritually, how can we fast from Jesus?

How can we fence the table?

What about those traditions that believe in a closed table (that not everyone is able or should partake in the Lord’s Supper)? I personally don’t believe in keeping a closed table (except for extreme situations), but I appreciate the wisdom behind it. I certainly agree that it would be nearly impossible to fence the table through digital mediums. Yet, I also think its nearly impossible to fence the table in normal situations. One will inevitably have the same problems in either situation. We won’t know about secret sins and we will always struggle to determine how sincere repentance is. Furthermore, what’s to stop someone from just going to another church (a problem that is exacerbated in non-denominational contexts)? At the end of the day, you can only do so much as a minister.

What if not everyone has access to our services?

This is an especially important question for congregations that have predominantly older members. At my church, we have several people that do not have access to the internet or a computer. How can they participate? To be honest, I haven’t quite figured this out. These same people are also difficult to connect with during normal times as our church experience becomes increasingly digitised. For example, your church may no longer print weekly bulletins to care for the environment, but this will affect the same group of people. That doesn’t mean it’s not a good move, it just means that it will take some creativity to keep certain people connected.

The Church has already shown it is capable of such creativity. Communion can be served in homes to those who are sick or can’t physically make it to the service. Spiritual Communion is offered to those who physically can’t digest food because of illness. Furthermore, I would argue that just because some people are not present for the Eucharist, doesn’t mean we shouldn’t take it. Families will go on holiday, People will move, and beloved members will die, but these situations should not preclude the church from celebrating the Lord’s Supper.

What happens if people watch the service at a later time (or what if the service is pre-recorded)?

This is perhaps the most interesting question I have pertaining to this issue. There are some very practical solutions that might mitigate this (such as a Zoom call), but the underlying issue is mediation. As discussed, presence can be mediated across both space and time. Receiving a letter is a great example of this. How does this work with communion though? An analogous situation would be listening to a sermon podcast. A sermon addresses a particular audience and situation, a certain time and place. As the Spirit speaks through the sermon as the Word of God, God speaks to particular lives and into specific problems. In the sermon itself experience live by a congregation, the Spirit will speak through these words quite differently to each person (many times, it is very different than the preacher intended!). But what happens when I listen to a recording of that same message? Yes, I may experience different things. Depending on the length of time between its delivery and my hearing, I may not sense the urgency because the situation has changed. But, can the Spirit still speak to me through this recording? Of course! The Spirit does that every day when we open up God’s word– a collection of narratives, history, poetry, and letters that were never addressed to us but nevertheless continue to speak us in our contexts. In a similar manner, I believe the risen Christ can meet us, even if the service is pre-recorded, or if we aren’t partaking the elements at the same time. I, however, would not encourage people to partake in this way if they are able to participate in or watch a live service.

What about Spiritual Communion?

In this time of isolation, many churches such as the Church of England have turned to the practice of Spiritual Communion. From their Guidance

on Spiritual Communion:

“The term ‘Spiritual Communion’ has been used historically to describe the means of grace by which a person, prevented for some serious reason from sharing in a celebration of the Eucharist, nonetheless shares in the communion of Jesus Christ.”

This practice of Spiritual Communion is well attested throughout the history of the Church, even if it ought to be a rare practice. Generally speaking, Spiritual Communion is only for those who cannot physically partake of the elements, but earnestly desire to be in union with Christ. We could imagine people on their deathbed who are too weak for food. Other instances may include believers imprisoned for their faith. They are both unable to partake in the elements because they have none and no one is able to serve them. Spiritual Communion is, therefore, an amazing blessing and means of grace for these types of situations.

However, I do not think Spiritual Communion is the best way forward in the situation we find ourselves in. Firstly, the vast majority of us are still able to partake in the elements. We have no issue with physically ingesting the bread and wine. Secondly, even in our isolation, most of us are not shut out from the outside world like the prisoner is. As discussed, human presence is able to be mediated to us and we are able to watch and participate in a worship service. Thus, because we are neither like the person in prison or the one on their deathbed, Spiritual Communion does not aptly fit our circumstance (though for some people during this time, it absolutely does). Thirdly, Spiritual Communion seems to only be for individuals or small groups of people. As far as I am aware, the practice was never meant to be applied for a global church.

Finally and most importantly, Spiritual Communion, as it is practised today, is predicated on the same theological reasoning that informs what I have proposed here. Though there is great freedom of expression in the Church of England, Spiritual Communion is typically incorporated into a normal Eucharistic prayer. So, during a livestreamed or pre-recorded service (In the cleanest corner of the vicar’s home), the minister will lead the virtual congregation through the service as usual. They might include a prayer or explanation about Spiritual Communion before the proper Eucharistic prayer. The minister will partake of the elements on screen while the rest of the congregants watch and receive the sacramental blessing of the Eucharist.

This practice of Spiritual Communion only ‘works’ if presence can be mediated through technology. If human presence cannot be mediated, then the congregation is not truly gathered with the priest. Thus, the priest is only taking communion by himself as a private event (this would not necessarily be a problem in Catholic or some Anglo-Catholic understandings of the priesthood). If communion is by definition a corporate event, then even the priest cannot celebrate the Eucharist (unless they celebrate it with their family). Furthermore, if presence cannot be mediated, then how can the sacramental blessing be received by people whose only access to the event is through technology? These issues are even more complicated if the service is pre-recorded as now the spiritual blessing of communion must be mediated through both space and time.

It seems that this practice of Spiritual Communion may be appropriate in certain circumstances, but is unnecessary for the majority of Christians in this season of isolation. If the Church of England is willing to innovate in such means as to allow for Spiritual Communion in this way, then they ought to allow baptised members in good standing to partake of the elements in their homes following the guidance above. As far as I am aware, to do so would be entirely in accordance with canon law.

A final note and a final appeal

Thank you for reading my proposal. I do apologise for the length, but this issue is important and demands a few more words than usual. You might not agree with my conclusions and reasoning. We are in strange times and I admire those who look to the traditions of the Church as their anchor. More than ever, we need faithful Christians to witness to the power of the risen Christ. The Church must reflect the light of Christ to the dark hopelessness of our world. More than ever, we need to experience afresh the risen Christ; more than ever, we need the Eucharist. My final appeal is this: if we partake of the bread and wine in faith, even if we are alone in isolation, the risen Christ might still choose to meet with us in this ‘less than ideal’ way. God is often found in the ‘less than ideal’, and Jesus is happy to meet us where we are.

God is often found in the ‘less than ideal’, and Jesus is happy to meet us where we are.

Further Reading

“A Question I Didn’t Get Answered in Seminary: Should We Take Communion Remotely?” by Uche Anizor, Darrian Lockett, and Charlie Trimm. The Good Book Blog. (24.4.20). https://www.biola.edu/blogs/good-book-blog/2020/a-question-i-didn-t-get-answered-in-seminary-should-we-take-communion-remotely?fbclid=IwAR0D4XZBUHhv4lPgYPwHr6lZ1JRGDzIMKvDRjV-amOBTM5KwIKbqoSKIk1g

“DIGITAL COMMUNION: HISTORY, THEOLOGY, AND PRACTICES” by John Dyer. (23.3.20). https://j.hn/digital-communion-summary-of-theology-practices/

“Can Baptism and the Lord’s Supper Go Online?” by Bobby Jamieson. The Gospel Coalition. (25.3.20). https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/article/baptism-lord-supper-online/

“(How) can we celebrate Holy Communion as ‘online’ church?” by Ian Paul. Psephizo. (26.3.20). https://www.psephizo.com/life-ministry/how-can-we-celebrate-holy-communion-as-online-church/

“Online Communion Can Still Be Sacramental” by Chris Ridgeway. Christianity Today. (27.3.20). https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2020/march-web-only/online-communion-can-still-be-sacramental.html?fbclid=IwAR0eaPosCXNUtLXfP6g4Zp_bZeopYGQAuYF8nhLOMQlw0HbIm5PTFUVD4oo

“Whether one may Flee from digital worship: Reflections on sacramental ministry in a public health crisis” by Kyle Kenneth Schiefelbein‐Guerrero. Dialog. (23.3.20). https://doi.org/10.1111/dial.12549

“THE PAIN OF THE UNCOMMUNED” by Katherine G. Schmidt. Daily Theology. (29.3.20). https://dailytheology.org/2020/03/29/the-pain-of-the-uncommuned/

“Christ is Really Present Virtually: A Proposal for Virtual Communion” by Deanna Thompson. St. Olaf College. Lutheran Center for Faith, Values, and Community. (26.3.20). https://wp.stolaf.edu/lutherancenter/2020/03/christ-is-really-present-virtually-a-proposal-for-virtual-communion/

“THE LORD’S SUPPER IN LOCKDOWN? NO.” by Garry Williams. (31.3.20). https://www.pastorsacademy.org/blog/nova/the-lord’s-supper-in-lockdown-no./?fbclid=IwAR1Jc4idZnzXumEVTqsvDrnKa54NeX35EqBufywGbcQKDIZdZKHfGFkPh48

“Online Communion amid Pandemic? A Theological and Political Reflection” by Celine Yeung. Medium. (21.3.20). https://medium.com/@celineyeung/online-communion-amid-pandemic-a-theological-and-political-reflection-c171167dbc41

5 Comments

Leave your reply.