In the Gospel According to St. Mark, Jesus introduces and institutes the Eucharist Feast in very few words:

And as they were eating, he took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to them, and said, “Take, this is my body.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, and they all drank of it. And he said to them, “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many. Truly, I say to you, I will not drink again of the fruit of the vine until that day when I drink it new in the kingdom of God.” (14:22-25)

The purpose of this blog series is to point to the literary structure and devices which Mark uses and demonstrate their interpretive import, or theological significance, when applied to the passage in view. Each post will trace one of three themes in Mark and demonstrate their point of convergence in the passage above. Put another way, I will reflect on three themes in Mark that are big enough that the reader can use this reflection to see the ways in which every single passage in Mark 1-14 sets up the institution of the Eucharist Feast.

A Man to Tame the Wilderness and Make it Grow

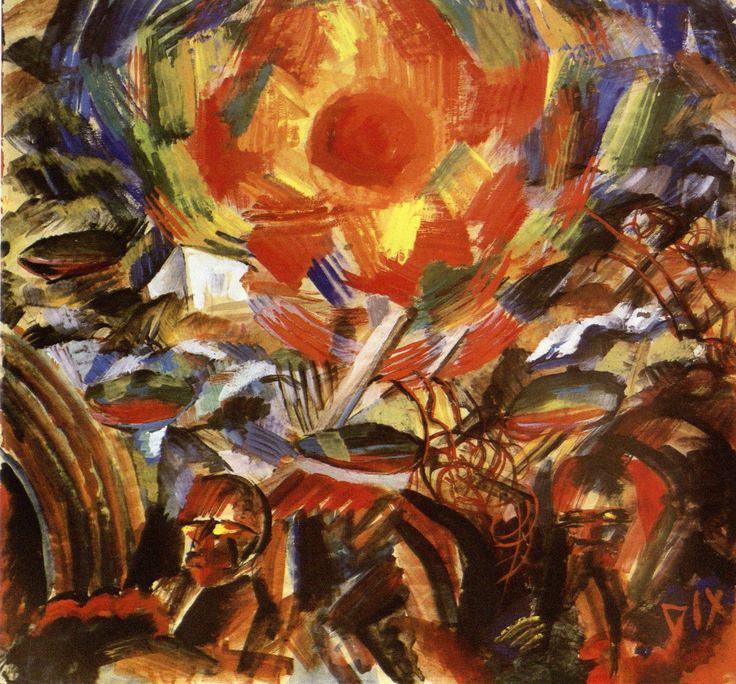

In the cryptic words of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, “Mark’s whole Gospel tries to show that Jesus has lived the one perfect solar year of a human sun, a human heart.” (Fruit of Lips, 61) In Mark’s gospel, Jesus certainly operates on a different plane than do his disciples, a plane of which they have next to no understanding, and Mark’s whole gospel is “built,” per Rosenstock, on this discrepancy between what Jesus knows and what the disciples do. The glaring issue is that Jesus knows what time it is, and the disciples don’t. Jesus’ very first words are, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand.” (1:15) But the final words of Jesus’ nearest disciples are, “Tell us when will these things be?” (13:4)

The disciples are asking about the timing of Jesus’ apocalyptic prophecy in Jerusalem: “the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and the powers in the heavens will be shaken.” (13:24-25) No doubt, these apocalyptic words point to concrete and immediate fulfillments in Jesus’ death, the destruction of the temple, and the impending upheavals in political order. But they also symbolize the change that, according to Jesus’ very opening line, has already place. Part of their disorientation is that they, like Javert in his final song, look up at a sky that they have only ever known to be full of stars that give order. What they are starting to realize is that Jesus has already begun to change the solar order.

The first change is that Jesus has replaced the Sun, and the rest of the changes follow from this. Scripture tells us from the very outset that all of the heavenly bodies are markers for power and time and, if Jesus is taking their places, their understanding of power and time will have to change as well. The stars are those that rule over the night, offering dim and distant light that foreshadows the coming daytime. The stars are the rulers of the churches (Rev. 1:20) and apostate teachers are “wandering stars” (Jude 13). Before the stars reference the Church, and not dependent on this interpretation, the heavenly bodies refer to other political powers. Per James Jordan,

Long before this, Joseph had seen the rulers of his clan as sun, moon, and stars. We see this even today. The flag of the United States of America has fifty stars, for the fifty states of our nation. The flags of oriental nations include the rising sun. The flags of Near-Easter countries feature a crescent moon. Sun, moon, and stars are symbols of world powers… They represent the angelic host in Judges 5:20, Job 38:7, and Isaiah 14:13. They represent the human host of the Lord as well, as we see from the promise to Abraham in Genesis 15:5, reiterated in Genesis 22:17, 26:4, and Deuteronomy 1:10. Christians “appear as stars in the world in the midst of a crooked and perverse generation.” (Philippians 2:15) (Through New Eyes, 55-56)

Men have looked to the moon—rightly—to discern the change in months, and Israel’s lunar calendar determined their festal calendar as well. All nations who wanted to eat allowed the cycles of the sun to determine the proper times for sowing and harvesting. Naturally, the calendar began to rule, and human powers either invented gods to associate with these heavenly bodies, or they associated themselves with the heavenly bodies. Caesar’s soul was believed to have become a comet, Cassius points his sword towards Brutus, proclaiming, “Here, where I point my sword, the sun rises.” Mark’s gospel confronts an empire that already has a sun, moon, and stars, with Jesus Christ, who knows he is the New Sun, and a band of apostles who do not know that they are already stars in his new solar order.

The world that Mark describes is in dire need of a New Sun, because the old lights do not work. The world Jesus enters is, quite literally, a wild one. Compressing Matthew’s 201-verse account of the beginning of Jesus’ ministry into just 22 verses, Mark emphasizes details that evoke a sense of wildness. John baptizes en ereimo, or “in the wilderness,” a word he will use four times. (1:3, 4, 12, 13) In the wilderness, Jesus is with “wild animals” (1:13), while John is eating “wild honey” and locusts and wearing camel’s hair (1:6) until he is caged up like an animal (1:14). The setting is no more civil once the action moves indoors. Jesus enters a synagogue, and a man immediately appears with an unclean spirit which convulses him and causes him to cry out in a loud voice (1:23, 26).

This wild and desolate world recalls the one which Jeremiah laments in a dirge based on the days of creation. Mark has already shown us a wild world with new light, and a poem like this one is likely to have been in the background of his introduction:

I looked on the earth, and behold it was formless and void;

And to the heavens, and they had no light.

I looked on the mountains, and behold, they were quaking,

And all the hills moved to and fro.

I looked, and behold, there was no man,

And all the birds of the air had fled.

I looked, and behold, the fruitful land was a desert,

And all its cities were laid in ruins

Before the LORD, before his fierce anger. (Jer. 4:23-26)

As the only place in Scripture that repeats the “tohu vebohu” Genesis 1:2, Jeremiah 4 clearly signals Genesis 1-2. What I am arguing here is that Mark draws from Jeremiah 4. If I am right, then he is, by virtue of drawing from Jeremiah 4, also signaling Genesis 1-2.

These are the ways in which Jeremiah signals Genesis. That the earth is “without form and void” (Jer. 4:23) reminds us of Genesis 1:2. The verse in Genesis continues: “darkness was over the face of the deep;” this corresponds to Jeremiah, in which the heavens “had no light.” In Genesis, “the Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters;” in Jeremiah, there is no hope in view, as “all the birds of the air had fled.”[1] When Jeremiah says that there “was no man,” he points us to the time in the garden when “no small plant of the field had yet sprung up” because “there was no man to work the ground.” (Gen. 2:5) Why was there no growth in Eden? Because God had not sent a man to work it. Why was there no growth in Jeremiah’s Israel? It is not that there was no man, but that the men who were there were incompetent to effect actual growth: “my people are foolish; / they know me not; / they are stupid children; / they have no understanding. / They are ‘wise’—in doing evil! / But how to do good they know not.” (Jer. 4:22)

Every line of Jeremiah 4:23-26 matches an element in Mark’s world. Like Jeremiah, Jesus sees no light, no man, and no birds, and the temple is not yet in ruins, but the synagogue has demons in it (1:23). When he arrives in Jerusalem, he will find that the fruitful land will not have borne fruit (11:12-14; 12:1-12); he looks around “with anger” (3:5; 10:41).

Into Mark’s wild and desolate world appears at last a man who can effect actual growth, and so there is hope.[2] One way of organizing Mark’s gospel, taking a cue from what we have already mentioned from Rosenstock, is according to the first new solar year, in which Jesus, as New Sun, determines the seasons. He comes in a desolate winter, and he effects a true springtime when he begins sowing seeds. In his first extended discourse, Jesus explains that “the sower sows the word,” and explains the kingdom of God in three parables about the planting and growth of seeds. (4:1-34) The seeds are the word, but the seeds can also be disciples: “Those that were sown on the good soil are the ones who hear the word and accept it and bear fruit, thirtyfold and sixtyfold and a hundredfold.” (4:20) Just as springtime is signaled by the first blooming buds, Mark’s springtime is signaled by the first sign of kingdom order: Jesus heals Simon’s mother, and she begins to serve him. (1:29-31)

When these seeds grow, the trees that grow in the kingdom of heaven make space for birds to nest in their shade (4:30-32), a sign of hope that Jeremiah was not blessed to see. Jesus’ journey, which we will discuss in more detail in another section, is the blistering summer during which Jesus’ disciples, the “good seed,” grow under his care (8:22-10:52). Three times does Jesus admonish and remind them that the goal of their life is to take up their crosses and follow him (8:34-38; 9:35-37; 10:42-45). When they return to Jerusalem, Jesus talks about the desolation and destruction that is to come, ready to harvest fruit but not finding any in the city. He expresses his frustration at their fruitlessness in the parable of the fig tree (11:12-14) and the tenants in the vineyard (12:1-12). While this is not the most determinative way of structuring Mark, Rosenstock’s claim is both provocative and constructively suggestive, and it helps us understand both the progress of Jesus’ ministry and one of its dominant metaphors. The insights of the above paragraphs are summarized in the following table:

| Season | Meaning | Structuring Mark |

| Winter | Time of desolation and no growth; no sun | 1:1-15 – John appears in the wilderness |

| Springtime | Sunlight appears; seeds are sown and begin growth | 1:16-8:21 – Jesus appears and calls his disciples, exorcises and heals, begins teaching and preaching to the masses, gives special care to disciples |

| Summer | Sunlight intensifies; seeds which have taken are tended toward greater growth, with an eye toward coming harvest | 8:22-52 – Jesus takes his disciples on a journey, rebukes them for their blindness, and teaches them three times the cost of following him |

| Harvest | Harvester returns to plants expecting to extract fruit | 11:1-16:8 – Jesus returns to Jerusalem, discussing the destruction of the temple and the end of the age, telling the parables of the vineyard the fig tree, and being harvested himself, completing “the first solar year” |

As we have said, this is the beginning of the gospel of Jesus Christ, the man who has arrived in the world that was formless and void, heading a cast of heavenly bodies that gives light and order to the world, bringing back birds, and working within God’s creation so that it might bear fruit which could be given back to God in thanksgiving. A new solar order means a new calendar, and a new calendar means new feasts. When the “the man” institutes a new feast during the Feast of Unleavened Bread during the Passover, he is starting a new world order.

[1] Birds and men are often paired in moments of new creation. Think Noah and the dove, Moses and leaving Egypt on the wings of an eagle.

[2] Significantly, where Jeremiah sees no bird, Jesus “sees” the Holy Spirit descend like a dove. And where Jeremiah saw no light in the heavens, we have demonstrated above that Jesus is the new sun who gives light to the world.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.