This summer, I got to read through Ephraim Radner’s Time and the Word: Figural Reading of the Christian Scriptures. When we flipped the calendar to August, and I traded theology for middle school literature, sharpening the transition from student to teacher, I was surprised to discover how theologically rewarding my experience would be.

I want to tell you two stories from my classroom about figural readings of To Kill a Mockingbird and then turn them into an argument for reading great literature figuratively.

Charlottesville, VA and Maycomb County, AL

The Monday directly following the events in Charlottesville, VA, my Hispanic and African-American 8th grade students and I opened our texts, read the mysterious line, “Maycomb County had recently been told it had nothing to fear but fear itself,” and wondered together at what it might mean.

My students inferred logically that Maycomb was being told this because they were fearing something. Grammatically, they decided that because the object of fear is, generally speaking, danger, the most dangerous thing the county faced was whatever fear they currently had.

Two more students who were not only logically and grammatically sharp, but also thoughtful about the narrative context, added that Maycomb was uncomfortably quick to condemn members of the Haverford family on nowhere near enough evidence. The citizens of Maycomb County were also spooked by the Radley Family: no one knew how they made a living, they kept their shutters closed up on Sundays, and the rest of the family’s goings on were things of hearsay and legend. At the outset of the book, our class is engaged in a core question: What does Maycomb County have to fear about this fear? What will it cause if it doesn’t dissipate?

My job is not to be a pastor, a father, a brother, a political lobbyist, a soothsayer, or a counselor. I don’t teach theology, the Bible, economics, political science, social studies, jurisprudence, history, or racial reconciliation. It’s not my job to discuss current events. I teach middle school literature and composition. We congregate five times a week to read novels and write sentences.

As we read novels, what I do get to do is lead my students socratically into encounters with the very real figures who inhabit the pages of To Kill a Mockingbird and the very real place called Maycomb County.

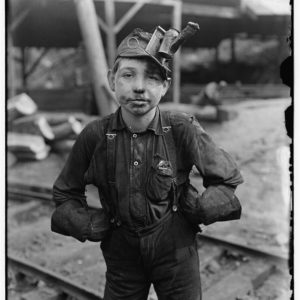

Why Burris Ewell doesn’t have to go to school

Although my students may not be directly affected, or even very aware of this month’s events in Charlottesville, they encounter plenty of difficulty at home. I teach in inner-city Phoenix, in a neighborhood called Maryvale. Many of its residents are not documented citizens of the United States, only 4% of adults hold college degrees, and many households do not have two supportive parents. We feed a good number of our students all three of their meals each day on the state’s dime. The children in my classes have enough to think about at home–we don’t need to add to it by discussing Charlottesville.

In Chapter 3 of To Kill a Mockingbird, Scout pleads with Atticus to let her quit going to school. When Scout determines that she is likely to lose her case, she brings up Burris Ewell; somehow he is allowed to skip school. Atticus’ response is firm: “Sometimes it’s better to bend the law a little in special cases. In your case, the law remains rigid. So to school you must go.”

I asked my students why Atticus bent the law for Burris but not for Scout. My students’ first answers had a good amount of truth to them. First, Scout is Atticus’ daughter, and he’s directly responsible for her upbringing. So to school she must go. Next, Atticus sees more potential in Scout than he does in Burris. So to school she must go.

The next answer was the sharpest one of the day: Scout has a good father at home who is giving her regular moral education through principle and example. Burris doesn’t have a mother, and his father is “contentious.” We find out later that he’s also spent a great deal of their money on “green whiskey” and has allowed his children to go hungry. Folks like Burris don’t know better, and they’re exempt from things that many others of us are not.

Knowing what this particular student’s life at home, I was both (a) not surprised at how easily he was able to recognize Burris, given this student’s own experience, and (b) very surprised at the composure this student was able to keep and the lucidity with which they were able to speak about such a difficult thing.

Reading Middle School Literature Figurally

Although I teach my students read grammatically, consider texts in their literary context, apply insights from their studies in American history, and bring to the table their own moral convictions, this is by no means exhaustive of what it means to get the full meaning of our texts.

In their encounter with the subtle and pernicious prejudices of the “good folk” in Maycomb County; their recognition of their own selves within Burris Ewell; the diminutive but upstanding young gentleman, Little Chuck Little, who doesn’t know where his next meal is coming from; Scout, who is full of curiosity, furiosity, and innocence; the young becoming-a-man named Jem; and Atticus Finch himself; my students are encountering real people. In the children, they are encountering non-historical, but very real types of the incarnate Christ who was born as a man, who “grew in wisdom and stature and in favor with God and man.”

They’re being asked to wrestle with our overarching unit question: “Who is a good citizen of Maycomb County, and why?” My boys will memorize a portion of one of Atticus’ speeches and, in their encounter with his fatherhood, encounter the fatherhood of God himself; “mystically, not by analogy,” as Zizioulas has wonderfully differentiated.

So I extend the argument for the figural reading of Scripture to the figural reading of great literature: As my students encounter the Good, the True, and the Beautiful in these figures, they encounter Christ himself, and by the good providence of God, from whom all gifts of grace come, will the Holy Spirit who hovers over creation not lead those who are humble into truth and obedience through these pages?

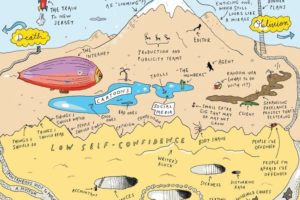

Even though they are not being asked to think about the historical city of Charlottesville, they are being asked to think of a non-historical, though very real city called Maycomb. This is Tolkien’s argument in “On Fairy Stories.” If they can, through the work of their imaginative and moral faculties, become good citizens of Maycomb, they will become good citizens of Maryvale (their home), and of Charlottesville. And if we can humble ourselves to work together alongside all people who truly desire to become good citizens of this earthly city, as Jesus did when he came to make it his home, we will become good citizens of the New Jerusalem, the anti-type of all of our city-making and political imagination.

Depending on your theological categories, you could call this “reading literature sacramentally,” “bringing Christian values into the secular classroom,” or grateful interaction with non-canonical but still Spirit-filled work that deserves our devotional reading. I am especially grateful for that distinction of Zizioulas’: “mystically, not by analogy.” I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments about how this helps you think about the way you read Scripture or literature, the sanctity of teaching, or sacramental encounters in other school subjects.

1 Comment

Leave your reply.