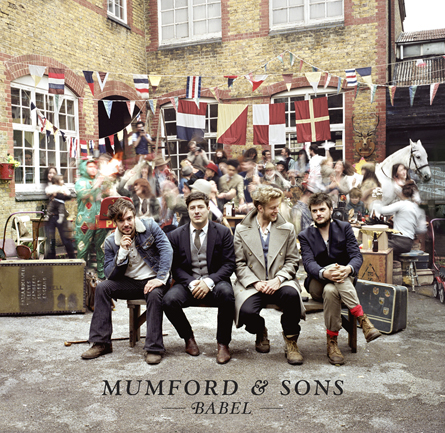

Last week Mumford & Sons released their new album, Babel. It’s a great album. Not as great as Sigh no More, but I like it holistically. In many ways, this new album follows the strengths of the previous album, especially in utilizing the crescendo effect (though it is a bit predictable). The most intriguing aspect of the album is — once again — the odd association of biblical imagery alongside swear words. I’d like to start my review with that infamous song as it thematically sets up my interpretation of the album as a whole.

In the tenth track, Broken Crown, we have another Mumford & Sons song in which the F Bomb is used. If you recall my earlier post on the use of the F Bomb in P.O.D.’s most recent album, I also addressed the use of the F Bomb in Little Lion Man by Mumford & Sons. There I suggested that the use of the word was legitimate given the context. But is it the same in this instance? First of all, I just want to know, does Mumford have some sort of contractual agreement to designate one song (and only one song) to have the F Bomb in it in each album? And it’s not like they use any other swear words. It’s just the F Bomb! I just want to say that I find this kind of odd. At any rate, it’s quite clear that the F Bomb is used sparingly. And, in fact, in very similar contexts. In Little Lion Man the use of the F Bomb was intended to convey remorse and guilt, and this is even more true in Broken Crown as we’ll see. At the opening of the song, it appears that there is some sort of temptation going on. Mumford expresses his weakness and admits that his heart was flawed. It appears that whatever temptation had expired, the result was transgression. Then comes the refrain:

Crawl on my belly ’til the sun goes down.

I’ll never wear your broken crown.

I took the road and I f***ed it all away.

Now in this twilight how dare you speak of grace.

With these lines I contend that Mumford is describing the Fall of Man. “Crawl on my belly” could be a reference to the curse placed on the serpent who tempted Adam and Eve in the Garden (Gen 3.14). The rejection of the ‘broken crown’ is then most likely a dismissal of the serpent’s temptations of a rival kingdom (perhaps drawing in imagery from Jesus’ temptations), even after being consigned to the fate of the serpent (i.e. crawling on his belly). To refer to the fallen state of all humanity in this context as “I f***ed it all away” is both thematically relevant and, given the darker vibe of the song, tonally appropriate; it doesn’t feel forced. If the use of the F Bomb was appropriate in Little Lion Man, then it is so much more so in this instance. And then, to end with “Now in this twilight how dare you speak of grace” puts everything in perspective (as well as tears in the eyes). Of course, in the biblical narrative God clothes the nakedness of Adam and Eve directly after their sin (Gen 3.21). That was an extension of grace that humanity did not deserve, and Mumford’s lyrics communicate this beautifully.

The connection with the Adamic Fall of Genesis 3 is made more plausible by the additional allusions to Genesis 1-11 in the album. Taken from the biblical story about the confusion of languages in Genesis 11, the album uses the motif of languages and tongues to express the intricacies of love and relationships. Essentially, the imagery of the Tower becomes an analogy for tearing down the walls of a lover’s heart. This is made especially clear in the opening title-track, Babel, and the thematic thread is woven through the whole album. This is combined with other biblical images from the early bits of Genesis. In the second track, Whispers in the Dark, Mumford uses this imagery from Genesis 6-9 and the tale of Noah’s Ark:

Spare my sins for the ark, I was too slow to depart

I’m a cad, but I’m not a fraud, I’ve set out to serve the Lord

Additionally, the multiple references to wandering and traveling in such songs as Holland Road and Hopeless Wanderer, could possibly be allusions to the story of Cain in this broader reflection on Genesis 1-11, since Cain is consigned to wander the earth after murdering his brother (Gen 4.12: You shall be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth). Placing the track Hopeless Wanderer directly before Broken Crown sets up the biblical imagery of that song quite well, from Cain to Adam. If indeed, the imagery of wandering is designed to have resonances with the story of Cain, then Broken Crown‘s retelling of Adam’s Fall becomes even more explicit.

In broad brush strokes, then, it seems that Mumford & Sons are allegorizing the tale of Genesis 1-11 as a way to communicate a love story. The key events and figures that are chosen — Babel, Noah, Cain, Adam — tell the biblical story in reverse order. The album is not a chapter-by-chapter interaction with the Genesis text, of course, but nevertheless a correspondence does emerge. In fact, the final song Not with Haste, with its idyllic references to green pastures, fair suns, healed scars, and lack of sadness, appears to reflect on the original state of creation in Genesis 1. Perhaps there is an intuition here that is designed to point forward to the end of Revelation in chapters 21-22. Speaking canonically, when we tell the biblical story in reverse order from Genesis 11 and the Tower of Babel on through to Genesis 1 and the creation of the cosmos, what comes next? Well it’s Rev 21-22. Of course, the end of Revelation is designed to replicate the imagery of Genesis 1 and so returning to the “Garden” in the final track of Mumford’s album explains why this song carries an eschatological ring to it — “They’ll heal our scars. Sadness will be far away.” Thus, I suggest that Not with Haste contains a conflation of Genesis 1 and Rev 21-22. This I contend is the framework of Babel; it is a tale of love utilizing the matrix of Genesis 1-11. Though it provides more of the structure to the album than an interpretive key; the biblical imagery is clearly not the main aim of the album and the parallels are a tad loose.

This review has primarily focused on the broader aspects of the album. I could of course try to describe the sound and vibe of each song, but you’d have a better experience listening to it yourself. Babel is an album that gets better with each listen, but it admittedly feels more generic than their previous effort. I find the track Broken Crown incredibly moving, but this is in fact a noticeable exception. The lyrics of the album as a whole feel like they should have spent a little more time in the oven. By way of contrast, the lyrics on Sigh No More were so gripping to me, but this just isn’t the case with Babel. Sadly, I think the tongue that was confused here was Mumford’s.

15 Comments

Leave your reply.