Since the twentieth century, no topic has shaped the philosophical conversations more than the question of authority. It is not that the topic wasn’t brought up previously, certainly the Reformation and the Revolutions in America and France centered on the topic, but the fervor with which the debate raged in academic circles during the twentieth century (and 21st for that matter) is unique in the course of the Great Conversation. There are probably two reasons for this: First, the twentieth century’s dialogue had more participants who were willing to understand authority without the concept of God. Second, the debaters in the twentieth century felt a certain luxury understanding personal autonomy (or self-rule) in light of the material success of the Western world.

The great political and social experiment of a democratic republic in many ways came to fruition in the twentieth century. The concept of personal autonomy saw its roots in the refusal of the magesterium, or the authority of the master or teacher in the Roman Catholic Church during the Protestant Reformation. That refusal extended to the natural rights philosophy of the American and French Revolutions, as well as the English Bill of Rights during the reign of William and Mary.

The twentieth century saw benefits from the acceptance of personal autonomy both politically, with things like racial integration and women’s suffrage, and economically, with the rise of the middle class. So today, we see the rise of personal autonomy as the means to the ends of our free society.

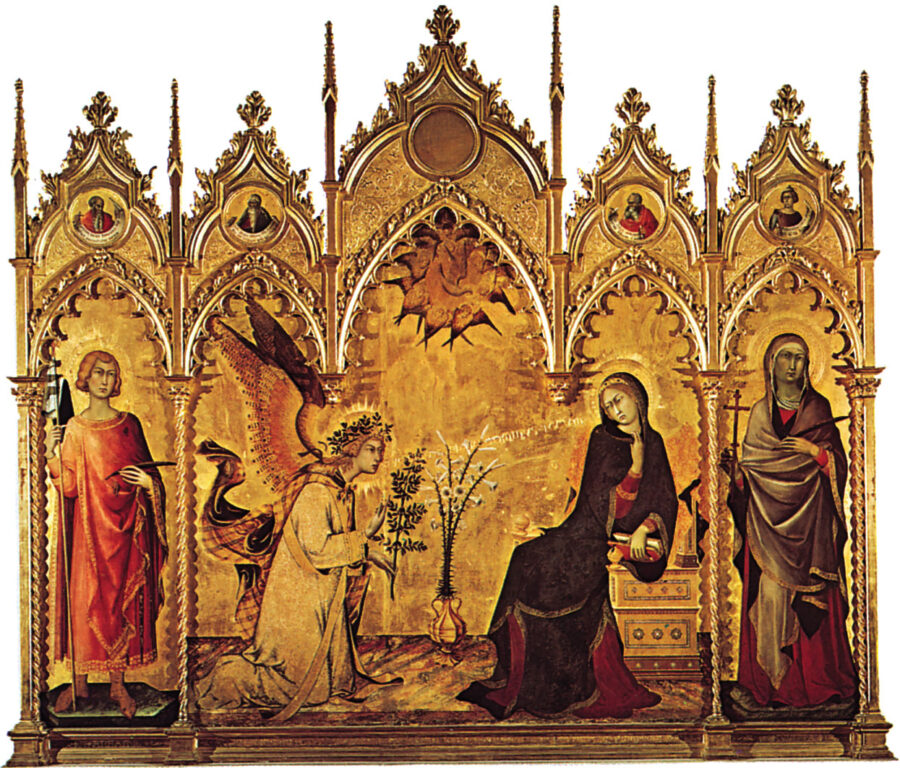

Here’s the rub: The Western world spent nearly two thousand years informed by the concept of the divine right of kings, the Roman Catholic Petrine theory of apostolic succession (the idea that the Pope inherited his authority from Peter who Christ, in their opinion, appointed head of the Church), and a more loosely defined idea of perpetual classism in which God simply willed for some to be kings, aristocracy, serfs, etc. What is true about all three of these ideas that dominated Western life for so long was that God’s authority (rightly or wrongly interpreted) was at the center of these viewpoints. The Reformation by no means abolished the notion of the authority of God, but certainly introduced a notion of at least a limited autonomy that really didn’t exist before in the West. Allowing for individuals to read and interpret Scripture for themselves gave the individual a sense of autonomy that was destined to overthrow the social order of the day.

Many of the Reformers, including Luther himself, didn’t support such a change in the existing class structure, but certainly many other movements arising from the Reformation, including the majority of Anabaptists, were very much in favor of the freedom of the individual to live subject only to his conscience and his interpretation of the will of God with all of the essential social and economic changes that would come from such a belief. The twentieth century saw the perception of authority taken to new extremes.

The biggest shifts in the meaning of personal autonomy came with the near universal acceptance of modern materialism as defined by scientific and political expertise. The culture wars of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have been centered around the ideas of modern social and political liberalism and the acceptance of Darwinism. The conservative forces within the culture wars correctly recognized the implications of this sort of liberalism and Darwinism, the denial of God in the public sphere.

My next post will explore how the two camps that arose out of this historical predicament have been portrayed, and to what end their philosophical assumptions ultimately will lead. But my question for you this week is this, What is the basis for self-rule? Why are we free to rule ourselves? Were we created that way or does the individual simply have an inherent power that governments, religious institutions, and economic institutions have to recognize? If we remove God as the basis for self-rule, can that self-rule be sustained? I would be interested to hear your thoughts on the implications of the denial of God for the future of personal autonomy.

7 Comments

Leave your reply.