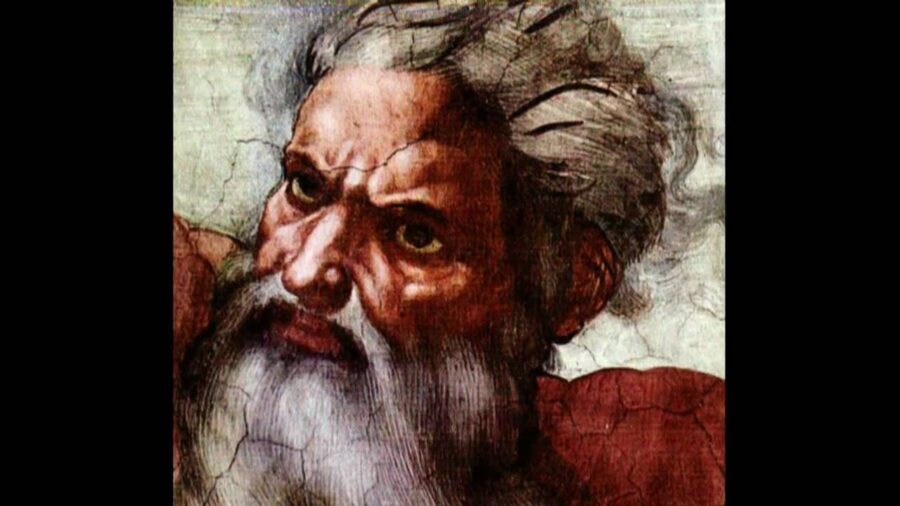

Evil things happen in this world, and yet God is still somehow sovereign.

This is perhaps the hardest part of Christian theology to accept and understand. How is God sovereign over the persecution of Christians around the world, over the acts of ISIS, over world hunger and poverty, or over smaller evils like my own depression, pain, and anxiety?

The answer might be eerily similar to the answer to how a perfectly good Father is sovereign over the crucifixion of his own son, Jesus Christ.

We worship a God who breaks our minds’ molds of good and evil. Just as the onlookers of the crucifixion perceived it an evil act, so have we perceived acts as evil throughout history and even in our own lives.

As humans trapped in temporal cause-and-effect relations, we are unable to see the layers of complexity that overlay even one evil action. Think of the story of Job in the Bible. Job’s livestock and his children were destroyed by the hand of God (Job 1:11f). These are only perceived as evil actions because the natural law of justice makes us think that it’s not fair. This is the precise response of Job’s friends who blame Job citing conventional wisdom that “those who plow iniquity and sow trouble reap the same” (Job 4:8). The reader knows Job’s innocence but also feels the weighty truth of the proverb.

Job’s final response gives us the true resolution:

“I know that you can do all things;

no purpose of yours can be thwarted.

You asked, ‘Who is this that obscures my plans without knowledge?’

Surely I spoke of things I did not understand,

things too wonderful for me to know.

“You said, ‘Listen now, and I will speak;

I will question you,

and you shall answer me.’

My ears had heard of you

but now my eyes have seen you.

Therefore I despise myself

and repent in dust and ashes.”

(Job 42:2-6)

I have noticed a sense of injustice in my own pain and suffering as a result of evil. I say to myself, “it’s just not fair…what did I do to deserve this?” I, with Job, despise myself for saying these things, and we ought to likewise despise ourselves for looking at the evils of this world and thinking, “God surely isn’t willing these evils.”

“But doesn’t that make God evil?” We might ask. Any appearance of evil on God’s part is a sign, an imprint, of the eternal decree of election. In order that God might elect Jesus Christ, and therefore us in him, he must first will to become Jesus Christ. This willing is a condescension, a humiliation, and a type of rejection and reprobation.

In a free act of divine love, God rejects pure godhood by accepting humanity into himself. In our history, this divine act of election is imaged by both good and evil. The good images God’s election of humanity, and the evil images God’s rejection of pure divinity. These are revealed together on the cross, where God rejects Jesus Christ whole also accepting Jesus as the representative sacrifice for the humanity he accepted into himself.

Every evil act, every sin, and every good deed, every blessing, can be recontextualized under the paradigm of the eternal divine decree to be God for us in Jesus Christ.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.